Copy link

Preoperative Anxiety in Children

Last updated: 05/09/2023

Key Points

- Pediatric preoperative anxiety occurs in up to 60% of patients, especially at the time of inhalational mask induction of anesthesia.1

- There are short- and long-term consequences of preoperative anxiety, including increased risk of emergence agitation and health care avoidance.

- Anesthesiologists use pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic modalities to treat preoperative anxiety with variable effectiveness.

Introduction

- Needle phobia is common in pediatric patients. Given the heightened anxiety that children experience prior to anesthesia, the majority of their anesthetic inductions are inhalational. Oral midazolam is the most common anxiolytic prior to mask induction, followed by parent present induction of anesthesia.

- For older children with an intravenous (IV) catheter inserted prior to induction, cold numbing spray, local anesthetic topical patches, or subdermal lidocaine decrease the discomfort of IV placement.

- Regardless of the type of induction, inhalational or IV, children commonly experience preoperative fear, which is underrecognized and undertreated.

- Anxiety arises from feelings of powerlessness, confusion, and compromised security.

- Risk Factors for preoperative anxiety include:

- Younger age

- Temperament

- History of child and/or parental anxiety

- Developmental delay

- Prior medical visits

- Short-term effects of undertreated perioperative anxiety include:

- Increased anesthetic requirements

- Increased postoperative pain

- Increased risk of emergence delirium

- Decreased parental and patient satisfaction

- Beyond the immediate perioperative period, children with undertreated anxiety may develop postoperative maladaptive behaviors for 2 weeks to 6 months, which include;2

- Generalized separation anxiety

- Sleep disturbances (night terrors, nightmares)

- Enuresis

- Aggression towards authority

- Posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms.

- Risk Factors for postoperative maladaptive behaviors include:

- Prior negative surgical experience

- History of poor induction compliance

- Parental anxiety

- Preoperative anxiolysis treatment approaches widely vary due to the lack of standardized national guidelines, heterogenous patient populations, and resource inequities.

Pharmacologic Treatment for Preoperative Anxiety

- Pharmacologic adjuncts are the most common method of preoperative anxiolysis in pediatric patients.

- There are various routes of administration for anxiolytics that do not rely on IV access.

- Oral (per os [PO])

- Intranasal (IN)

- Intramuscular (IM)

- Per rectum (PR)

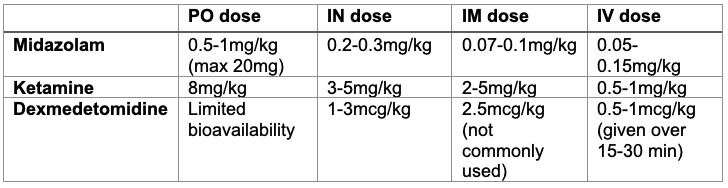

- Typical anxiolytic classes include benzodiazepines, N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor antagonists, and alpha-2 receptor agonists (Table 1).

- Midazolam (class: Benzodiazepines)

- Available via IV, PO, IN, and IM routes.

- Typical doses include the following, with care to titrate to liver and kidney function and mental state:

- IV: 0.05 to 0.15mg/kg

- PO (most common route prior to mask induction): 0.5 to 1mg/kg (max of 20mg)

- IN: 0.2-0.3mg/kg with a nasal atomizer

- IM: 0.07mg/kg to 0.1mg/kg

- Advantages: Produces consistent anxiolysis; short onset time when given IV; produces anterograde and retrograde amnesia.

- Disadvantages: Oral administration is associated with bitter taste, although taste enhancers can be effective; IN administration can cause nasal irritation and burning sensation; when not given IV, the time to therapeutic effect can be variable; 5-10% of patients develop paradoxical reactions that result in increased anxiety.

- Ketamine (class: NMDA receptors antagonist)

- Available via IV, PO, IN, and IM routes

- Typical doses include:

- IV: 0.5 to 1mg/kg

- PO: 5-8mg/kg

- IN: 3 to 5mg/kg with a nasal atomizer

- IM (most common route): 2 to 5mg/kg, often given with an anti-sialogouge such as glycopyrrolate

- Advantages: Produces a dissociative sedation; maintains respiratory drive; potent analgesia.

- Disadvantages: Excessive secretions; dysphoria; hallucinations; nystagmus; oral bioavailability less than 25% and most commonly coadministered with another anxiolytic if given PO.

- Dexmedetomidine (class: alpha-2 receptor agonist)

- Available via IV, PO, IN, and IM routes

- Typical doses include:

- IV: 0.5 to 1mcg/kg administered over 15 to 30 minutes

- PO: Not approved for use, but early studies are promising

- IN (most common route prior to mask induction): 1 to 3mcg/kg via nasal atomizer

- IM: Not commonly used, but 2.5mcg/kg has shown effectiveness in adults and children

- Advantages: Analgesic component; possible anti-emetic properties; maintenance of respiratory drive.

- Disadvantages: Long onset time (at least 30-60 min), may be arousable to stimuli; oral bioavailability less than 15%.

- Midazolam (class: Benzodiazepines)

Table 1. Common pharmaceutical options for anxiolysis in pediatric anesthesiology

Nonpharmacologic Treatment for Preoperative Anxiety

- Parent present induction of anesthesia (PPIA)

- Early studies suggest that PPIA is not as effective as midazolam.3 However, newer studies suggest that preoperative parent education and behavior modifications may improve PPIA effectiveness.

- Advantages: Nonpharmacologic; obviate separation anxiety from the child’s perspective; high parent satisfaction.

- Disadvantages: Increased parent anxiety; usefulness of the PPIA is highly dependent on parent anxiety and cooperation; theoretical intraoperative sterility concerns; potential disruption to operating room workflow since the parent will require a chaperone back to the waiting room.

- Preoperative education programs

- Preoperative education preparation programs have been in existence in various forms since the 1960s.

- Initially, they sought to improve trust between the child and the medical team.

- Various modalities are used to convey content, including videos, pamphlets, tours, role-playing, behavior modeling, and workshops.

- Almost all have been shown to reduce some aspects of preoperative anxiety.

- ADVANCE (Anxiety reduction, Distraction, Video modeling & education, Adding parents, No excessive reassurance, Coaching and Exposure/shaping) trial4:

- Preoperative workshop that promoted family-centered care around the child’s surgical experience.

- Utilized videos, pamphlets, and coaching via telephone encounters to teach parents distraction skills. Also provided exposure therapy with mask training at home for patients to reduce anxiety on the day of surgery.

- Midazolam group and ADVANCE group of patients both had decreases in anxiety and better mask compliance. However, the ADVANCE patients had further reductions in postanesthesia care unit (PACU) length of stay, less fentanyl use in PACU, and decreased severity of emergence delirium.

- ADVANCE (Anxiety reduction, Distraction, Video modeling & education, Adding parents, No excessive reassurance, Coaching and Exposure/shaping) trial4:

- Certified Child Life Specialists (CCLS)

- CCLS aid in the preparation of children and family members for medical procedures in order to promote effective, healthy coping for both present and future health care experiences.

- CCLS reduce perioperative anxiety by promoting age-appropriate techniques such as role-playing, behavior modeling, distraction techniques, and expectation-setting.

- Immersive Technologies

- Several different technologies, from phones and tablets to virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), are useful tools that decrease preoperative anxiety.

- Smartphones and tablets

- Offers some level of distraction, however, are limited by relatively small screen size, lack of novelty, and inconvenient viewing while supine.

- Projectors

- The Bedside Entertainment Relaxation Theatre (BERT) has been well studied, and consists of a battery-powered projector that is clamped onto the head of the gurney and a large white corrugated plastic screen mounted to the foot of the child’s bed (Figure 1).

- The screen is large enough to fill most of the child’s field of vision, providing a near-immersive experience while still allowing patient interaction between parents and hospital staff. Popular streaming platforms are easily projected onto the white corrugated screen while the patient is being transported from the preoperative area to the procedure area.

- Smartphones and tablets

- Several different technologies, from phones and tablets to virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), are useful tools that decrease preoperative anxiety.

Figure 1. Bedside Entertainment Relaxation Theatre (BERT) setup on a patient gurney in the preoperative area.

-

-

- Augmented Reality (AR)

- Provides a partial immersive experience as patients view superimposed holograms atop the real world (Figures 2,3).

- Different types of hardware exist, from phone-based visors, corded visors, and all-in-one head-mounted displays.

- Advantages include maintenance of eye contact between patient, family, and providers; ability to assess patient eyes during mask induction; and phone-based headsets allow access to a variety of traditional multimedia applications that are familiar to providers.

- Disadvantages include cost; headsets may easily break; need to keep charged; provider training; comfort; and sanitation.

- Augmented Reality (AR)

-

Figure 2. Inhalational mask induction with an augmented reality headset on a patient.

Figure 3. An example of an augmented reality (AR) hologram seen with an AR headset during inhalational mask induction.

-

-

- Virtual Reality (VR)

- VR provides patients with a completely immersive experience by utilizing a head-mounted display (Figure 4).

- It typically uses computer-generated environments to create a calming and distracting environment, using a combination of commercially available and custom-built software.

- Reductions in anxiety and pain have been observed for minor pediatric procedures such as venous access, oncologic procedures, burn care as well as in the perioperative setting.5

- VR has been used for inhalational induction of anesthesia with significant anxiety reduction.

- Contraindications include history of seizures, migraines, motion sickness, claustrophobia, and open facial wounds.

- Advantages include complete immersion from the health care setting and a large library of content compared to AR and projectors.

- Disadvantages include difficulty achieving a seal with a facemask under the VR headset during inhalational mask induction, cost, and inability to see the patient’s eyes during induction.

- Virtual Reality (VR)

-

Figure 4. A patient using a virtual reality (VR) headset in the preoperative area.

- Other nonpharmacologic anxiolytics that have been explored include parental acupuncture, clown therapy, music therapy, provider behavior training, low sensory environment, and hypnosis. All of these modalities are utilized less commonly but have shown promise in reducing anxiety prior to anesthesia.

References

- Kain ZN, Mayes LC, O'Connor TZ, Cicchetti DV. Preoperative anxiety in children: predictors and outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(12):1238-45. PubMed

- Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Maranets I, et al. Preoperative anxiety and emergence delirium and postoperative maladaptive behaviors. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(6):1648-54. PubMed

- Manyande A, Cyna AM, Yip P, Chooi C, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for assisting the induction of anaesthesia in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(7):CD006447. PubMed

- Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Mayes LC, et al. Family-centered preparation for surgery improves perioperative outcomes in children: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(1):65-74. PubMed

- Tas FQ, van Eijk CAM, Staals LM, et al. Virtual reality in pediatrics, effects on pain and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis update. Paediatr Anaesth. 2022;32(12):1292-1304. PubMed

Other References

- Stanford Medicine Children’s Health. CHARIOT Program. Accessed April 13, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.