Copy link

Cardiac Implantable Electronic Devices: Pacemakers

Last updated: 08/02/2023

Key Points

- Implantable pacemakers are a subset of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs). The use of CIEDs has increased exponentially, given that patients with cardiac disease are living longer and that device indications have expanded.

- CIEDs are commonly encountered in the perioperative setting, and anesthesiologists must be aware of the potential for electromagnetic interference and the perioperative management of pacemakers, including the indications for magnet use and device reprogramming.

Indications for Pacemakers

- In classic CIEDs, leads are placed in a transvenous fashion, either from the left subclavian (typical) or right subclavian vein.

- Common indications for pacemakers include the following:1

- Symptomatic bradycardia

- Complete, 3rd-degree atrioventricular (AV) block

- Advanced 2nd-degree AV block (Mobitz type II)

- Neurocardiogenic syncope

- Congenital complete AV block

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Long QT syndrome

Types of Pacemakers

- A single-chamber pacemaker has 1 lead in the right atrium or ventricle.

- A dual-chamber pacemaker has 2 leads: 1 in the right atrium and 1 in the right ventricle. Both leads can sense and pace their respective chambers.

- Univentricular pacemakers have a lead in the right ventricle.

- Biventricular pacemakers are often used in heart failure patients with severe conduction disturbance and/or ventricular desynchrony.

- Biventricular pacemakers pace both ventricles via a lead in the right ventricle and a lead in the coronary sinus. They are used for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), which can improve survival in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) less than 35%.

- Patients with decreased EF may also be at risk for ventricular arrhythmias, and so a defibrillator component (CRT-D) can be added.

- Leadless pacemakers do not require lead implantation into the venous system and are implanted directly into the right ventricle. These provide single chamber pacing and generally do not have magnet responsiveness.1

Pacing Modes

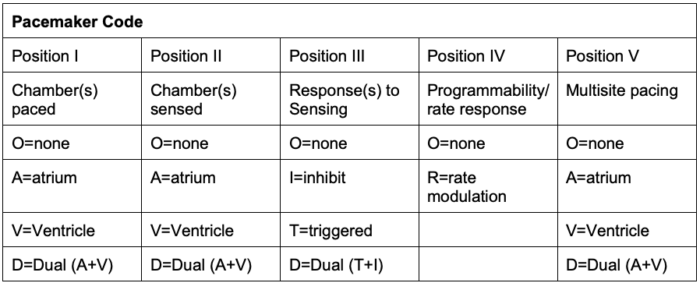

- Pacemakers are classified according to their pacing modes (Table 1).2

Table 1. Generic pacemaker code developed by the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology and the British Pacing and Electrophysiology Group. Adapted from Bernstein et al. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25(2):260-4.

- Position IV indicates rate modulation or rate responsiveness, where the pacemaker can change the heart rate to meet physiological needs.

- Position V indicates the areas of multisite pacing for patients with heart failure.

Electromagnetic Interference

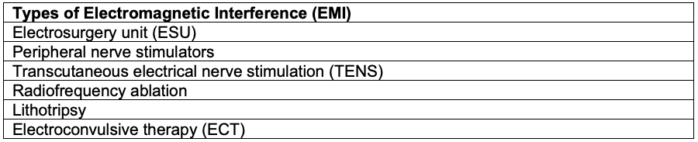

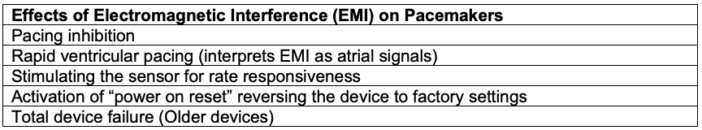

- Electromagnetic interference (EMI) is the term for potential disruption to the device function if it is close to an electromagnetic field generated by external sources, such as electrocautery, lithotripsy, radiofrequency ablation, etc. (Tables 2 and 3).3,4

- The most common source of EMI is the electrosurgery unit (ESU), which is commonly known as electrical cautery.

- The risk is higher the closer the ESU is to the implanted device.

- Inhibition of pacing is the most concerning sequelae of EMI.

- Alterations in pacemaker function can lead to severe bradycardia or even cardiac arrest.

Table 2. Types of Electromagnetic Interference

Table 3. Effects of electromagnetic interference on pacemakers

Perioperative Management

Preoperative Evaluation5

- The type of device should be identified by reviewing the patient’s chart or the device identification card.

- The device interrogation report should be reviewed to determine the indication for the pacemaker, date of implantation, battery life, and the underlying rhythm.

- The American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) practice advisory recommends device interrogation 3-6 months prior to a scheduled procedure.

- There should be at least 3 months of remaining battery life left prior to the procedure.

- Whether the patient is pacer-dependent should be determined preoperatively, as EMI inhibition of the device could lead to severe bradycardia or asystole.

- In urgent or emergent cases, obtaining this information can be challenging.

- CIED manufacturers have customer service numbers available that can be reached at all times to obtain information about the device.

- The CIED team (electrophysiology) may interrogate the pacemaker on site and can reprogram it.

- Preprocedure discussion and planning should occur amongst the anesthesiologist, electrophysiologist, and proceduralist/surgeon.

Magnet Use

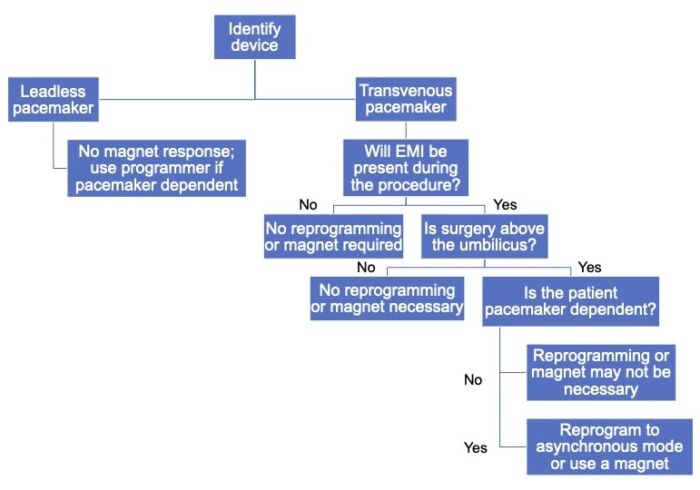

- It is critical to understand the device’s response to a magnet and whether it should be used during the procedure.

- In general, a magnet applied to most pacemakers results in asynchronous pacing at a specific rate. However, this is not always the case, so the specific device response should be verified.

- The removal of the magnet should revert the device to its previous settings.

- Leadless pacemakers do not have a response to magnet placement.6

Procedure

- The procedure itself may or may not allow magnet use. For example, a magnet cannot be placed in the surgical field or if the patient is positioned prone.

- Procedures above the umbilicus result in a higher risk of EMI, especially when ESU is used, so a magnet should be placed or the pacemaker should be reprogrammed in those cases.

Intraoperative Management

- Standard ASA monitors should be used. Invasive monitoring may be needed depending on patient comorbidities and the nature of the procedure.

- Transcutaneous pacing pads should be placed in case there is an urgent need for pacing or cardioversion/defibrillation.

- EMI should be minimized when possible. If EMI is likely to occur and the patient is pacer-dependent, the pacing function should be altered to a synchronous mode.

- The dispersing pad for the ESU should be placed such that the ESU current will not cross the generator.

- The use of short, intermittent bursts of ESU, bipolar ESU, or ultrasonic scalpel (harmonic) is recommended.

- In the case of intraoperative bradycardia or inhibition of pacing, the ESU should be stopped to verify the ECG, and external pacing should be used if necessary.

Postoperative Management

- The preoperative pacemaker settings should be restored by removing the magnet or programming back to baseline. Emergency treatment measures such as transcutaneous pads should remain until this is done.

- The device should be interrogated if it was not done preoperatively.

- Removing the magnet should restore the pacemaker to previous settings, but in some circumstances, it should be interrogated again (e.g., extensive blood loss, electrolyte abnormalities, defibrillation/cardioversion, etc.).

Figure 1. Algorithm for the perioperative management of patients with pacemakers

References

- Cody J, Graul T, Holliday S, et al. Nontransvenous cardiovascular implantable electronic device technology - A review for the anesthesiologist. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021; 35(9): 2784-91. PubMed

- Berstein AD, Daubert JC, Fletcher RD, et al. The revised NASPE/BPEG generic code for antibradycardia, adaptive-rate, and multisite pacing. North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology/British Pacing and Electrophysiology Group. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002; 25(2): 260-4. PubMed

- Shulman PM. Perioperative management of patients with a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. In: Post T(ed). UpToDate. 2023. Link

- Crossley GH, Poole JE, Rozner MA et al. The Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) expert consensus statement on the perioperative management of patients with implantable defibrillators, pacemakers, and arrhythmia monitors: facilities and patient management. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8(7):1114-54. PubMed

- Practice advisory for the perioperative management of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: Pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, 2020: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on perioperative management of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Anesthesiology. 2020; 132:225-52. PubMed

- Tang J, Savona S, Essandoh M. Aveir leadless pacemaker: Novel technology with new anesthetic implications. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022;36(12):4501-4. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.