Copy link

Transgender and Gender-Diverse Patients: Anesthetic Considerations

Last updated: 02/16/2023

Key Points

- Transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) patients represent individuals whose sex assigned at birth and gender identity do not correlate as expected based on cultural norms and societal expectations. Individuals with varying gender identities can be under this TGD “umbrella,” including nonbinary, genderqueer, genderfluid, agender, or transgender.

- Anesthesiologists will care for TGD patients who may present for surgical care related to gender affirmation but may also require routine or emergent surgical care that is unrelated.

- Anesthesia practitioners should be familiar with the possible implications of prior gender-affirming care on anesthetic planning. The preoperative interview and exam should include questions about previous gender-affirming treatment when relevant to anesthetic planning. This may include questions about the potential for pregnancy, prior hormone use, current or past chest binding, and/or previous gender-affirming surgical procedures.

Introduction

- Transgender and gender-diverse (TGD) individuals have gender identities that are different from what would be expected based on their sex assigned at birth and cultural and societal expectations. By contrast, cisgender individuals have gender identities as expected based on their sex assigned at birth.

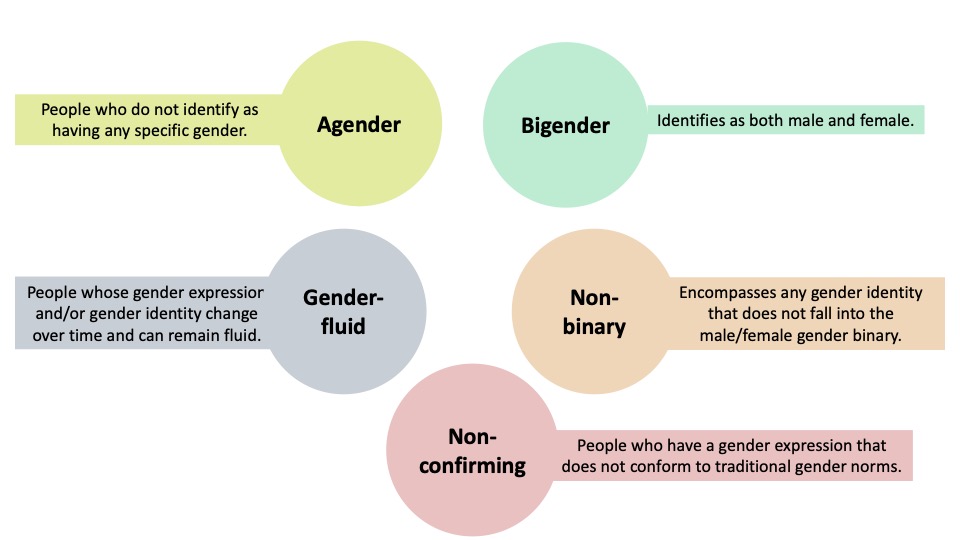

- Many different gender identities fall under the “gender-diverse” umbrella (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Definitions of some common identities under the gender-diverse umbrella.

- Additionally, within these groups, individuals may be described as transfeminine or transmasculine.

- Transfeminine is someone who is assigned male at birth (AMAB) and whose gender identity and/or expression is feminine.

- Transmasculine is someone who is assigned female at birth (AFAB) and whose gender identity and/or expression is masculine.

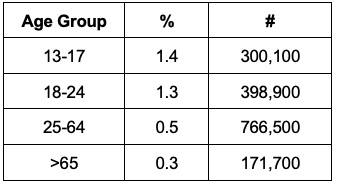

- Approximately 0.6% of the U.S. population over age 13 identifies as transgender, and the proportion of people identifying as transgender is higher in younger generations.1

Table 1. Proportion of the U.S. population in each age group identifying as transgender. Adapted from Herman JL, Flores AR, O’Neill KK. How many adults and youth identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. 2022.1

- TGD patients often use names and/or pronouns that more accurately reflect their identities as part of their initial social transition. These new names and pronouns might be different from what is expected based on their sex assigned at birth. It is critical that a patient is addressed with their chosen name and pronouns throughout the entire perioperative encounter. Affirming a patient’s name and pronouns is associated with better mental health outcomes and is the standard of care.

- As part of gender-affirming treatment, some TGD individuals may choose to utilize hormone therapy or undergo a wide range of surgeries to help achieve desired physical characteristics. These treatments could have implications for anesthetic planning. An anesthesiologist knowledgeable about gender-affirming care can plan accordingly to ensure optimal, affirming, and safe care.

Preoperative Testing

Laboratory Values - TGD individuals receiving gender-affirming hormone therapy are expected to have changes in common laboratory values. Hematocrit and creatinine change in more predictable ways, but liver enzymes and lipids may also be affected (Table 2).

- In general, lab profiles shift to favor the individual’s affirmed gender after about six months of therapy. It is then felt to be appropriate to interpret an individual’s lab results using reference values of cisgender individuals of the same gender identity.2,3

Table 2. Expected changes to lab values with gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Preoperative Pregnancy Testing

- Preoperative pregnancy testing is common in perioperative settings and is usually done out of concern for potential harm to the fetus as a result of the surgical procedure or from potential exposure to teratogens. Certain procedures, such as hysterectomy, intrauterine device placement, etc., may necessitate prior confirmation that a pregnancy is not present.

- Institutions may have their own policies regarding who should be tested and whether or not it is compulsory. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) recommendations do not require testing but recommend it be offered to patients of child-bearing age when the result would change management.4

- Some practitioners feel awkward when approaching this clinical question or may be confused as to who might need testing but reviewing the basic requirements for pregnancy should help identify which TGD individuals may or may not benefit from testing. Pregnancy generally requires that an individual have:

- uterus and ovaries;

- receptive vaginal/frontal sex; and

- partners who produce sperm.

- Testing is not indicated for transfeminine (AMAB) patients since they have never had a uterus or ovaries, but it may be indicated in transmasculine (AFAB) patients if they fit the criteria above.

- While testosterone use often results in amenorrhea, it does not reliably cease ovulation and is not a substitute for contraception. Its use in gender-affirming hormone therapy should not preclude testing if pregnancy is a concern.

- Pregnancy testing may contribute to gender dysphoria — the psychological distress and unease TGD people can experience due to the mismatch between their gender identity and sex assigned at birth. Ideally, patients should be informed ahead of time about the possibility of testing and be able to opt for whichever test is less distressing (urine or serum).

Impacts of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy

Drug Interactions

- There are no known clinically significant drug-drug interactions among common medications used as part of an anesthetic and those used for puberty suppression or gender-affirming hormone therapy.2,3

Perioperative Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) Risk

- A 2019 meta-analysis concluded there is insufficient evidence to routinely discontinue testosterone in transgender men undergoing scheduled surgeries.

- Evidence is less clear regarding estrogen use in transgender women. Analysis using individual risk factors is needed to inform decision-making.4 The emotional and physiological effects of abrupt cessation of estrogen, and the possibility of exacerbating gender dysphoria, must be weighed against the risk of VTE.

- The World Professional Association for Transgender Health and the University of California San Francisco guidelines reiterate that there is no strong evidence to suggest perioperative VTE risk is higher in transgender women who continued hormone therapy compared to those who stopped, in the absence of specific risk factors (e.g., smoking, family or personal history of VTE).6

Sugammadex

- Sugammadex is known to bind and lower free plasma concentrations of progesterone and thus, when administered to a patient taking hormonal contraception, requires additional counseling to use a nonhormonal backup method in the following seven days to avoid unwanted pregnancy.

- Sugammadex should be safe to use in TGD patients. For AMAB transfeminine patients on gender-affirming estrogen therapy, unintentional pregnancy is not a concern (as above). Additionally, while plasma levels of estrogen or progesterone may fall, a bolus dose of sugammadex is equivalent to missing one dose and is therefore, unlikely to have a significant impact on its gender-affirming effects.

- Importantly, for AFAB transmasculine patients that use a hormonal contraceptive, unintentional pregnancy may be a possibility if sugammadex is used. Counseling AFAB transmasculine patients about using nonhormonal backup methods of contraception for seven days should proceed exactly as with any cisgender woman.

Impacts of Other Gender-Affirming Treatment

Vocal Surgery

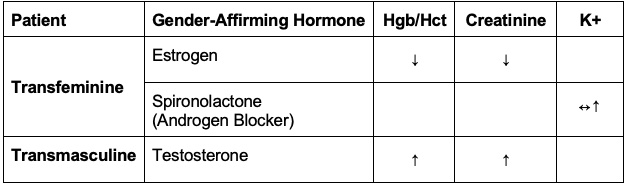

- It is important to determine if patients have undergone any procedures that change the vocal pitch by altering the laryngeal and thyroid anatomy. These have the potential to make mask ventilation, intubation, or surgical airway more difficult.

- Vocal feminization may be achieved by anterior glottoplasty, which functionally shortens the vocal cords by the formation of a web. Another technique is the VFSRAC (vocal fold shortening and retroplacement of anterior commissure) surgery (see video linked below in other resources). In both techniques, glottic size is reduced, and a smaller endotracheal tube may be required for future airway management.

Figure 2. Vocal cords before and after anterior glottoplasty. a: normal laryngeal anatomy, marking site of incision; b: de-epithelialization of anterior third of vocal cords; c: sutures used to approximate and close anterior third of vocal cords, forms glottic web after healing. Reproduced with permission from https://www.ricktroy.com/

- Vocal masculinization may be achieved via type III thyroplasty, where bilateral vertical strips are excised from the thyroid cartilage, resulting in decreased vocal fold tension and a lower vocal pitch.

- No specific guidelines exist regarding the safe timing of airway instrumentation for subsequent elective surgery.

Chest Binding

- Chest binding – compressing the chest tissue in order to create a flatter appearance – is a common practice among transmasculine individuals to improve dysphoria. Methods vary from using household items (duct tape, plastic wrap, or using elastic bandages) to compressive sports bras or commercially available undergarments designed for this purpose (“binders”).

- Long-term health effects of binding are not known, but the practice has been implicated in a variety of negative symptoms in several body systems. Most important to the anesthesiologist are the potential impacts on respiration and chronic pain.

Figure 3. A person wearing a chest binder. Source: Genusfotografen (genusfotografen.se) & Wikimedia Sverige (wikimedia.se), CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. Link

- A survey of 1800 AFAB adults who regularly participated in chest binding found:7

- a median daily use of 10 hours per day over a two-year period; and

- common complaints of pain (74%) and respiratory issues (50%).

- Lung volumes are also impacted by binding; however, the clinical significance is unclear.

- The inability to bind in the perioperative period may increase dysphoria. Patients may be reluctant to remove binders. Anesthesiologists should be aware of the practice and may need to include a discussion of when to discontinue and resume binding during their preoperative conversation. No official guidelines exist.

References

- Herman JL, Flores AR, O’Neill KK. How many adults and youth identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. 2022. Link

- Tollinche LE, Walters CB, Radix A, et al. The perioperative care of the transgender patient. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(2):359-66. PubMed

- Roque RA. Transgender pediatric surgical patients-Important perioperative considerations. Paediatr Anaesth. 2020;30(5):520-8. PubMed

- Pregnancy testing prior to anesthesia and surgery. American Society of Anesthesiologists Policy. Last amended: October 13th, 2021. Accessed October 15th, 2022. Link

- Boskey ER, Taghinia AH, Ganor O. Association of surgical risk with exogenous hormone use in transgender patients: A systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(2):159-69. PubMed

- Deutsch MB. Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People; 2nd edition. 2016. Link

- Peitzmeier S, Gardner I, Weinand J, et al. Health impact of chest binding among transgender adults: a community-engaged, cross-sectional study. Cult Health Sex. 2017;19(1):64-75. PubMed

Other References

- Roque, R. The Pediatric Transgender Patient. OpenAnesthesia. Published June 5, 2019. Accessed February 16, 2023. The Pediatric Transgender Patient: Foundations and Perioperative Considerations

- Yeson Voice Center. Vocal Fold Shortening and Retroplacement of Anterior Commissure Surgery. Yeson Voice Center. Video included with permission from the Yeson Voice Center, South Korea. Published February 12, 2020. Accessed February 16, 2023. Link

- Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. Published September 15, 2022. Accessed February 16, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.