Copy link

Status Asthmaticus

Last updated: 09/10/2024

Key Points

- Status asthmaticus is a medical emergency that involves an episode of severe asthma unresponsive to standard treatments.

- Without prompt treatment, the condition can rapidly deteriorate into acute ventilatory failure and death.

- A combination of inhaled albuterol, systemic steroids, adjunctive therapies, and potentially ventilatory interventions are used to treat this condition. Patients often require admission to the intensive care unit; most show improvement within 24-48 hours.

Background

- This discussion will focus exclusively on status asthmaticus. Please see the OA Summaries on bronchial asthma and anesthesia for asthma patients.

Definition

- Status asthmaticus is an acute and emergent episode of severe asthma unresponsive to standard treatments, including repeated courses of beta-agonist therapy, steroids, or subcutaneous epinephrine.1,2

- Severe asthma symptoms include hypoxemia, hypercarbia, and progression to respiratory failure.

- Onset can occur either slowly (days), often in inadequate compliance with asthma regimen or exposure to stressors, or the progression of symptoms may be abrupt and sudden (hours), often in the setting of significant exposure to triggers or allergens.2

Risk

- Any patient with asthma is at risk for this condition. Without prompt treatment, the condition can rapidly deteriorate into acute ventilatory failure and death.

- Risk factors for developing status asthmaticus include:

- Previous episode(s) of severe asthma exacerbation requiring intubation*

- Multiple asthma exacerbations requiring hospitalization despite chronic oral steroid regimen

- Chronic severe disease that results in a blunted hypoxic ventilatory response*

- Late presentation to emergency care*

*Indicates risk factors for mortality

Evaluation

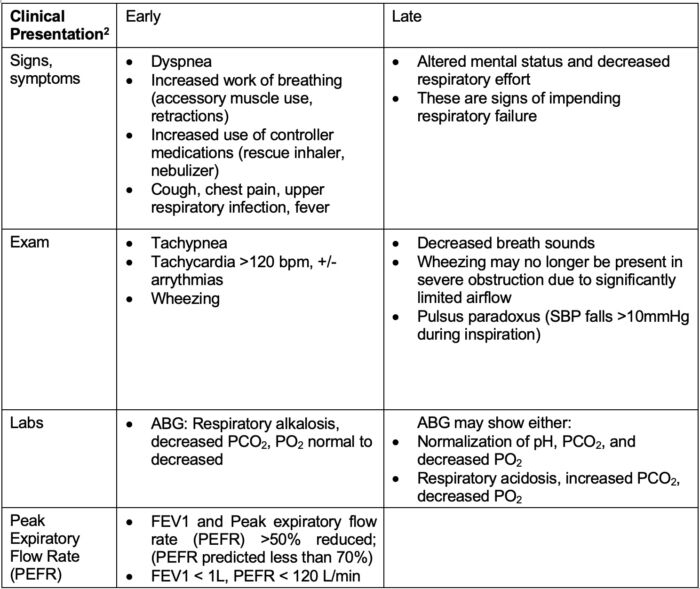

- Initially, patients present with dyspnea and tachycardia, showing signs of increased work of breathing and often, but not always, audible wheezing. As they exhaust themselves, attempting to breathe through the severe obstruction, respiratory effort declines, PaCO2 builds, and hypoxemia ensues.

- It is critical to identify signs of decreased effort, rising PaCO2, and loss of wheezing, as these are indicators of progression to respiratory failure.

Table 1. Stages of clinical presentation

- Pulsus paradoxus occurs due to the significant negative inspiratory intrathoracic pressure generated to ventilate through the obstruction. This increases right ventricular filling and shifts the myocardial septum leftward, resulting in increased left ventricular afterload and decreased stroke volume.

- Labs and imaging should be obtained to rule out other causes of respiratory distress. Additional studies include:

- ECG, troponins for cardiac etiology

- Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic profile

- Chest radiograph

- Point-of-care ultrasound

Management

- Status asthmaticus is a medical emergency that requires prompt treatment. Patients often require hospital admission for continued monitoring. Those who do not respond sufficiently to interventions (see below criteria) will require admission to the intensive care unit.

- PEFR fails to improve beyond 10%2, and PEFR improvement is not sustained for more than 2 hours.3

- Symptom improvement does not sustain more than 30 minutes.2

- Symptoms continue to progress toward respiratory failure.

Medications2-4

- Oxygen supplementation

- Systemic glucocorticoids

- Methylprednisolone 2 mg/kg loading dose; 0.5-1 mg/kg/dose q6h (max 60 mg/day) for pediatric patients; typically, intravenous administration.

- Adults: 40-80 mg per day for adults, typically oral administration.

- Bronchodilators

- Albuterol nebulizer: 2.5-5 mg q20 minutes x3 doses followed by q1h treatments

- Continuous albuterol: 0.15-0.5 mg/kg/hour (max 30 mg/hour) for pediatric patients; 10-15 mg over one hour for adults

- Inhaled anticholinergics (ipratropium)

- Typically used as an adjunct, studies are limited to determine if a significant benefit exists in this setting.

- Intravenous magnesium sulfate

- 25-75 mg/kg, max 2 grams over 20-30 minutes for pediatric patients; 2 grams for adults

- Monitor for hypotension

- They are typically used as adjuncts, as studies are limited in determining if a significant benefit exists in this setting.

- Systemic epinephrine

- Use is reserved for cases of anaphylaxis and cases in which ventilation is too poor for the use of inhaled beta-agonists.

- Anesthetic agents with bronchodilatory properties:

- Ketamine

- 1-2 mg/kg bolus given intravenously over 1-2 minutes (0.5 mg/kg/min); 0.5-2 mg/kg/hr infusion

- Rapid onset bronchodilatory effect is proposed to be secondary to sympathomimetic activity that increases catecholamine levels. Additional proposed mechanisms include effects at voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and acetylcholine receptors, reduction in nitric oxide levels, and reduced production of inflammatory cytokines5

- NMDA receptor antagonism produces sedation, generally preserves airway reflexes

- Monitor for hypertension, tachycardia, increased secretions, and lower seizure threshold

- Avoid in patients with preeclampsia, uncontrolled hypertension, elevated intracranial pressure, elevated intraocular pressure, liver dysfunction, epilepsy, etc.

- Propofol

- Rapid onset, mild bronchodilatory effect

- Monitor for hypercapnia, suppresses ventilatory drive

- Inhaled anesthetics (sevoflurane, isoflurane)

- Titrated to clinical response, side effects (hypotension, myocardial depression) limit dosing

- The requirement of specialized equipment and anesthesia provider presence limits use

- Desflurane is known to increase airway reactivity and bronchial smooth muscle tone and may precipitate bronchospasm. It is not a preferred agent in asthmatic patients.

- Ketamine

Interventions2-4

- Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (PPV)

- PPV functions to open narrowed airways to facilitate exhalation and reduce the work of breathing.3

- PPV may help prevent intubation by slowing the progression to respiratory failure while the medications take effect. However, there is not as much data to support this finding in asthmatic patients as there exists regarding its use in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations.

- Requires patient cooperation, +/- mild sedation as needed.

- Intubation and mechanical ventilation should be performed in patients with respiratory failure and those who have received maximal medical treatment but keep progressing toward respiratory failure.

- Sedative medications for intubation include ketamine and propofol as noted above. Paralytics may be utilized if ventilator desynchrony becomes problematic.

- All attempts should be made to maximize early medical intervention to reduce the need for intubation. Stimulation of instrumentation in the airway may worsen bronchospasm.

- High-flow nasal cannula – more studies are needed to evaluate its utility and benefit in status asthmaticus.

- Heliox (20% oxygen, 80% helium) lowers viscosity and increases laminar flow. However, higher oxygen concentrations are often required, limiting helium’s benefit. Data is limited to support its utility and benefit in this setting.

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is used in extreme situations when patients are refractory to the above treatments.

- Treatment is carefully weaned as the patient’s clinical status improves. Most patients show improvement within 24-48 hours of therapy. Further work-up for precipitating factors and complications should be performed for those who do not. Cardiac disease and comorbid pulmonary disease can worsen prognosis.

References

- Shah R, Saltoun CA. Chapter 14: Acute severe asthma (status asthmaticus). Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012;33 Suppl 1:47-50. PubMed

- Chakraborty RK, Basnet S. Status asthmaticus. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island, FL. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Link

- Howell JD. Acute severe asthma exacerbations in children younger than 12 years: Intensive care unit management. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2024. Accessed May 7, 2024. Link

- Cahill KN. Acute exacerbations of asthma in adults: Emergency department and inpatient management. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2024. Accessed May 7, 2024. Link

- La Via L, Sanfilippo F, Cuttone G, et al. Use of ketamine in patients with refractory severe asthma exacerbations: systematic review of prospective studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;78(10):1613-22 Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.