Copy link

Spine Surgery: Special Considerations

Last updated: 02/15/2023

Key Points

- Myelopathy from spinal cord compression often requires surgical decompression.

- Cervical neck pathology like atlantoaxial instability or cervical spine injuries add complexity to airway management during spine surgery.

- Prone positioning, neuromuscular monitoring, and the potential for high blood loss are important considerations when planning anesthesia for spine surgery.

- Patients should be kept euvolemic and mean arterial pressure should be maintained at 80-90 mmHg for patients with severe myelopathy or spinal cord injuries.

- Intraoperative neuromonitoring with evoked potentials may help detect injury during spine surgery.

Myelopathy

- Myelopathy occurs from the compression of the spinal cord.

- Symptoms may include pain, decreased balance, numbness/tingling/weakness in multiple dermatomes/myotomes below the injury, increased reflexes, and loss of bowel/bladder function.

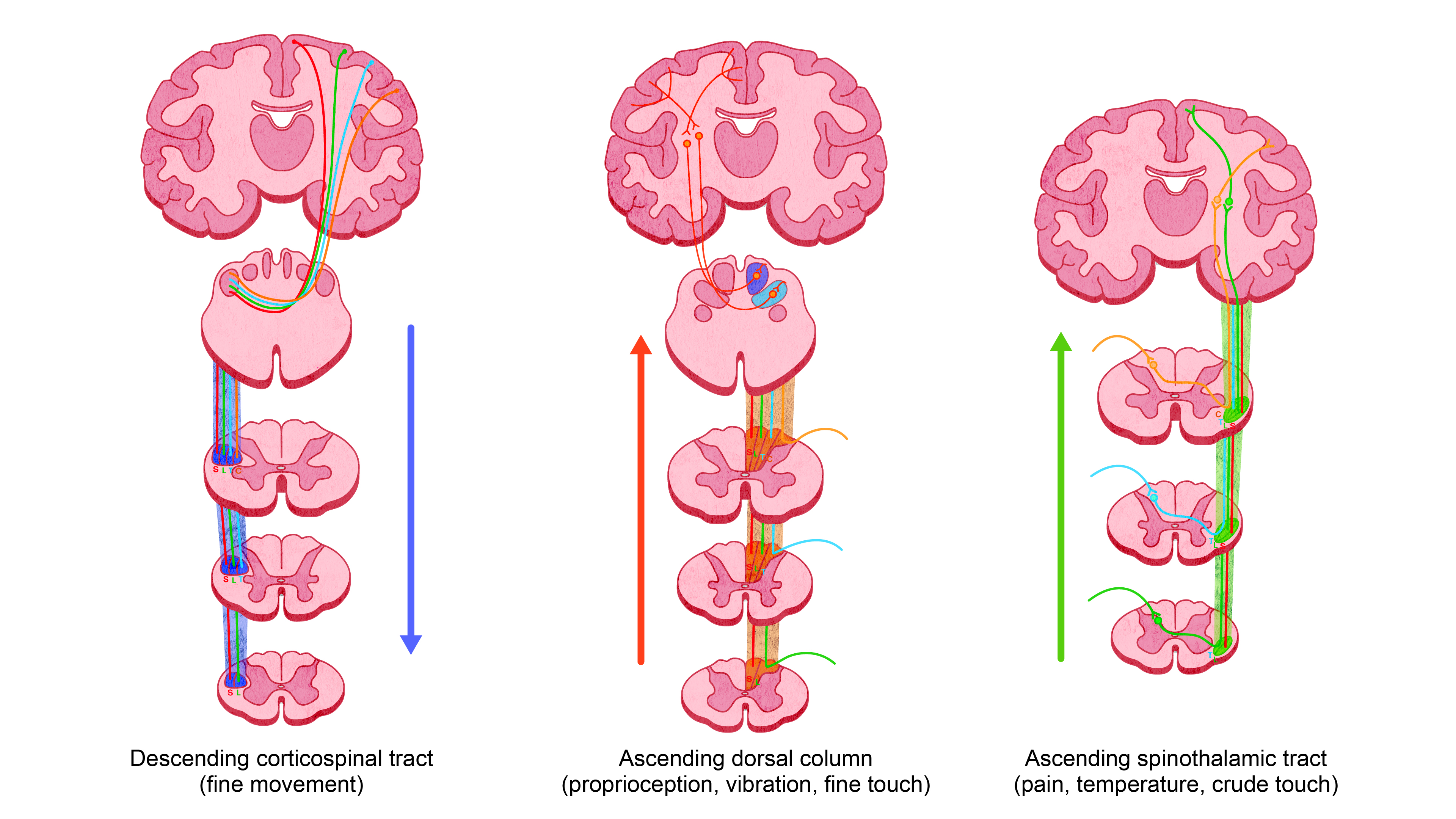

- Symptoms are due to the disruption of the descending corticospinal tract, ascending dorsal, and spinothalamic tracts. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Major ascending and descending tracts of the spinal cord. Redrawn from Kunam VK, et al. Incomplete cord syndromes. Clinical and imaging review. Radiographics. 2018; 38: 1201-22.2

- Differential diagnoses of myelopathy include degenerative spinal stenosis, disc herniations, rheumatoid arthritis, tumors, hematomas, spinal cord injury, vascular malformations, and inflammation.

- Treatment often involves surgical decompression.

- Radiculopathy (differentiated from myelopathy):

- It involves the pinching of a nerve root as it exits the spinal column.

- Symptoms are limited to the dermatome and myotome of the nerve being compressed.

- Paresthesias and lower motor neuron signs and symptoms (e.g., weakness, decreased reflexes, muscle wasting) occur in a single nerve root distribution.

Airway Management

- Special attention should be paid to the cervical neck range of motion, and every precaution should be taken to maintain the patient’s preoperative state. Patients undergoing thoracic or lumbar spinal surgery may have coexisting cervical spine disease.

- Video laryngoscopy, fiberoptic intubation (asleep or awake), and manual inline stabilization can all be used to prevent spinal cord injury during intubation.

- Care must be taken during neck manipulation in patients with atlantoaxial instability (e.g., Down syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, achondroplasia) or congenital cervical stenosis.

Anesthetic Management

Preoperative assessment – Special considerations include:

- cervical neck range of motion;

- assessment of restrictive lung disease due to spinal malformation;

- clear documentation of preoperative neurological deficits to correlate with intraoperative and postoperative exams;

- history of autonomic hyperreflexia;

- risk for hyperkalemia with succinylcholine use in patients with chronic spinal cord injury or severe myelopathy;

- Frailty assessment and prehabilitation should be considered, although evidence is limited.

Positioning – The majority of spine surgeries occur in the prone position.1

- During cervical spine surgeries, the patient is typically positioned in the reverse Trendelenburg position, with the neck flexed for the posterior approach and extended for the anterior approach.

- For lumbar spine surgeries, special tables (Jackson) optimize surgical exposure while minimizing abdominal compression of the inferior vena cava (IVC). IVC compression causes preload variability, hemodynamic instability, and shunting of blood through the epidural plexus leading to increased surgical blood loss.

- Eyes must be checked frequently (often every 15 minutes) to ensure the orbits are free of pressure to decrease the risk of blindness and retinal ischemia (see Postoperative Visual Loss summary).

- All pressure points must be padded.

- Attention must be taken to meticulously secure the endotracheal tube and prevent tongue compression ischemia during motor evoked potentials (MEPs) or neck flexion.

- Positioning of arms and legs should be neutral.

Maintenance

- Total intravenous anesthesia is typically used for the optimization of evoked potentials.

- Volatile anesthetics (>0.5 MAC) and muscle relaxants should be avoided or reversed after endotracheal intubation as they can affect evoked potential monitoring.

Fluid Management

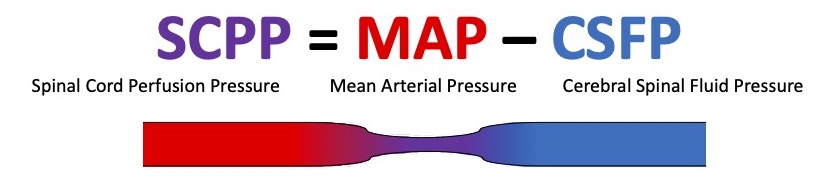

- Patients should be kept euvolemic to maintain a normal mean arterial pressure (MAP) and, therefore, spinal perfusion pressure (SPP). (See below)

- Volume status may be assessed by integrating clinical findings like MAP, pulse pressure variation, blood gases, urine output, estimated blood loss, and central venous pressure trends.

- Balanced crystalloids are often preferred to maintain plasma sodium and acid-base balance within normal ranges. Supplementing with colloids can replete intravascular volume while minimizing interstitial edema from excessive fluid administration.

Transfusion of Blood Products

- Transfusion thresholds are patient-specific and must consider comorbidities like ischemic heart disease.

- Generally, blood transfusions are recommended for hemoglobin less than 9 g/dL during surgeries with active bleeding and less than 8 g/dL postoperatively.3

- Consider tranexamic acid and cell saver for longer surgeries with high blood loss.

- Consider checking hemostatic parameters such as thromboelastography or coagulation studies for longer surgeries with high blood loss.

Pain Management

- Spine surgeries often result in significant pain, which can limit physical rehabilitation in the postoperative period.

- A multimodal pain regimen to limit the side effects of opioids is recommended. Long-acting opioids (e.g., sufentanil, hydromorphone) work synergistically with analgesic sedatives (e.g., dexmedetomidine, ketamine), scheduled acetaminophen, and lidocaine infusions. Celebrex and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications may be discouraged due to impaired bone healing.

- Consider enhanced recovery after surgery protocols utilizing modalities such as physical therapy and peripheral nerve blocks, although evidence is limited.

Blood Pressure Management

- To preserve SPP and prevent ischemia, MAPs should be maintained at the patient’s normal preoperative levels (Figure 2).

- A MAP of 80 – 90 mmHg in patients with spinal cord injuries and myelopathy should be targeted.1

- For lower-risk patients, MAP within 20% of the patient’s baseline should be maintained.

- Low dose phenylephrine infusions may be used after euvolemia is achieved.

Figure 2. Schematic of spinal cord perfusion pressure

Evoked Potentials

- Somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs) and MEPs are recommended during spine surgery to help detect impending injury to the sensory and motor pathways.4

- Electromyography (EMG) can identify injury to nerve roots during pedicle screw placement and other surgical maneuvers.

- Myelopathy causes a decrease in amplitude and an increase in latency of SSEP and MEPs.

- Early improvement in SSEPs and MEPs during decompression is associated with improved postoperative outcomes in patients with preexisting deficits.

- Please see the Evoked Potentials summaries for a detailed review.

Specific Considerations: Cervical Spine Surgery

- Airway management – see above

- Anterior cervical discectomies require retraction of the airway and cranial nerves, which could result in airway compression, swelling, or recurrent laryngeal nerve injuries.

- Endotracheal tube cuff pressure check during retraction may help reduce the risk of ischemia to the tracheal mucosa.

Specific Considerations: Thoracic and Lumbar Spine Surgery

- Restrictive lung disease – Patients with severe scoliosis may exhibit signs of restrictive lung disease. Pulmonary function tests may be warranted in some patients.

- Blood loss – Tumor resections, redo instrumentation, and multilevel procedures (e.g., congenital scoliosis) are often associated with increased blood loss.

- One-lung ventilation (OLV) – OLV may be requested in some thoracic spine surgeries, which can be achieved with the use of double-lumen endotracheal tubes and bronchial blockers. Please see the One-Lung Ventilation summary for a more detailed review.

- Air embolism – Specialized surgical tables are designed to minimize IVC compression and subsequently the pressure in the epidural veins. Although rare, a low central venous pressure can lead to an air embolism.

- Postoperative vision loss (POVL) – POVL is a rare complication of spine surgery. Risk factors include intraoperative hypotension, increased blood loss, prone positioning, increased surgery duration, use of a Wilson frame, administering a high ratio of crystalloids to colloids, advanced age, preoperative anemia, obesity, vascular disease, and male gender.5 Please see the POVL summary for a more detailed review.

References

- Gropper MA, Cohen NH, Eriksson LI, et al. Miller’s Anesthesia. Ninth edition. 2020. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc; Pages 1262-3, 1876, 1905-7.

- Kunam VK, Velayudhan V, Chaudhry ZA, et al. Incomplete cord syndromes. Clinical and imaging review. Radiographics. 2018; 38: 1201-22. PubMed

- Barrie U, Youssef CA, Pernik MN, et al. Transfusion guidelines in adult spine surgery: a systematic review and critical summary of currently available evidence. The Spine Journal. 2022; 22(2): 238-248. PubMed

- MacDonald DB, Skinner S, Shils J, Yingling C. Intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring – A position statement by the American Society of Neurophysiological Monitoring. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2013; 124: 2291-2316. PubMed

- Practice advisory for perioperative visual loss associated with spine surgery 2019: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force on perioperative visual loss, the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society, and the Society for Neuroscience in Anesthesiology and Critical Care. Anesthesiology. 2019; 130: 12-30. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.