Copy link

Spinal Anesthesia in Adults: Anatomy, Indications, and Physiological Effects

Last updated: 12/19/2023

Key Points

- Spinal anesthetics can often be used as the sole anesthetic, whereas epidural anesthetics are often used as an adjunct to spinal or systemic anesthesia.

- Absolute contraindications to neuraxial anesthesia include patient refusal, allergy to medication used, infection at the site, and severe coagulation abnormalities.

- Physiologic effects of spinal anesthesia can be profound and are related to the blockade of autonomic fibers.

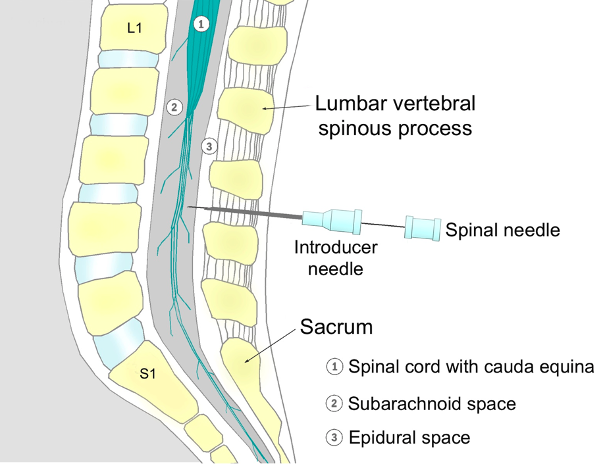

Anatomy

- The vertebral column consists of 33 bones, including 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 fused sacral, and 3 to 5 (most commonly 4) fused coccygeal vertebrae.1,2

- Spinal anesthetics target the lumbar and caudal regions, whereas epidurals have a wider range of applicability and include the thoracic space.

- Total cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume in adults is approximately 150 mL or 1.5-2 mL/kg. The spinal subarachnoid space is continuous with the intracranial space, and CSF flow is slow and idiosyncratic, relying on bulk flow and oscillation.1

- Ligaments provide support and stability for the spinal column. These structures are typically thicker and stronger lower in the column. Notably, the ligamentum flavum, a longitudinal structure along the dorsal spinal column, is thicker and more complete in the lumbar region.1

- The spinal cord thins from a cranial to caudal direction, with the cord terminating in adults at L1/2 and the dural sac at S2.1

- The epidural space is bounded by the bony structures of the spinal column, excludes the contents of the dura, and communicates with the paravertebral spaces via the spinal foramina, from which nerve roots exit.1

- The depth of the epidural space is maximal in the lumbar spine. In about 80% of adults, the distance from the skin to ligamentum flavum is 3.5-6 cm.1

- The Artery of Adamkiewicz (supplying the anterior spinal cord) is highly variable but most commonly enters the canal at the left L1 foramen.1

- The internal venous plexus, which drains the cord, is prominent in the lateral epidural space and ultimately empties into the azygous system.1,3

Figure 1. Principles of performing a spinal anaesthesia, by PhilippN, 2007, Wikipedia Commons.

Indications and Contraindications

Indications

- Spinal anesthetics can often be used in isolation as the sole anesthetic or with sedation for patient comfort.

- Typical surgical indications for spinal anesthesia include lower abdominal, perineal, and lower extremity surgery.1

- Epidural anesthetics are often used as an adjunct to spinal or systemic anesthesia and can include thoracic, abdominal, or lower extremity surgery. This can be performed with a single procedure known as a CSE (combined spinal-epidural).1

Contraindications

- Absolute contraindications

- Patient refusal, allergy to medication used, infection at the site, and severe coagulation abnormalities1

- Critical/severe aortic stenosis and high intracranial pressure1

- Spinal Metastases near the level of approach

- Relative contraindications

- Spinal abnormalities, previous spine surgery at the desired target, coagulopathy, fixed cardiac output states, and active infections1

- Autoimmune neurologic disorders may pose an undue risk, and careful consideration of risks and benefits must be weighed.1

Physiological Effects of Spinal Anesthesia

Central Nervous System

- Physiological effects will depend on the site of neural blockade, with the least physiologically disruptive technique being a “saddle block” of sacral nerves.1

- Rapid abolition of neural transmission at injection site, which is the intended goal of the procedure

- Blockade of autonomic fibers (up to 6 dermatomal levels above the site of injection) results in many of the side effects seen in other body systems.1

- Sensory changes occur within seconds, followed by loss of proprioception and motor function. Patients often describe perineal, then lower limb, sensory changes (typically warmth) within seconds of spinal anesthetic injection. This is followed by loss of temperature sensation, pain, and two-point discrimination, then loss of vibration sense, proprioception, and motor function over several minutes. Pressure sensation, proprioception, and motor functions may be retained despite surgical anesthesia. These are signs of a less dense neural blockade.

- Please see the OA Summary on differential spinal blockade. Link

Cardiovascular

- Rapid reductions in afterload and preload occur due to the blockade of sympathetic autonomic fibers.1

- Cardiovascular collapse within seconds may result in patients with little functional reserve due to these hemodynamic changes.1

- Most patients do not experience large swings in heart rate after spinals, though reflex tachycardia can follow decreased blood pressure. However, in some cases (typically younger and healthier patients) unopposed parasympathetic tone to the sinoatrial and atrioventricular node results in bradycardia and a low cardiac output state, particularly if cardiac accelerator fibers T1-T4 are affected.1

Pulmonary

- Neuraxial blockade impairs respiratory muscle function in a level-dependent fashion.1

- Reduced forced vital capacity, vital capacity, and expiratory reserve volume leads to subjective shortness of breath and atelectasis.1

- Block height reaching C3-5 directly impairs phrenic nerve function, resulting in central apnea requiring urgent airway management and ventilation.4

- Neuraxial opioids induce hypoventilation that may be prolonged.1

Musculoskeletal

- Neuraxial anesthesia has a wide range of direct and indirect effects on the musculoskeletal system.

- Impaired thermoregulation may result in involuntary shivering.1

- Spinal anesthesia provides excellent muscle relaxation for lower abdominal and lower extremity surgery.1

Gastrointestinal

- Neuraxial anesthesia leading to sympathectomy results in increased gut motility and therefore may prevent ileus, a common development with certain surgeries.1

Renal

- Blockade of the S2-S4 nerve roots can cause inhibition of bladder detrusor function, leading to urinary retention.1

- Prolonged blockade of detrusor function may lead to bladder distension or rupture in very rare cases.

- Acute kidney injury can result from prolonged hypotension and diminished renal perfusion.

References

- Brull R, Macfarlane AJR, Chan VWS. Spinal, Epidural, and Caudal Anesthesia. In: Miller’s Anesthesia. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1413-49.

- Woon JTK, Stringer MD. Clinical anatomy of the coccyx: A systematic review. Clinical Anatomy (New York, N.Y.), 2012;25(2):158–67

- Nieuwenhuys R, Voogd J, van Huijzen C, eds. Blood Supply, Meninges and Cerebrospinal Fluid Circulation. In: The Human Central Nervous System. Springer; 2008:95-135.

- Hawkins JL, Bucklin BA. Obstetric Anesthesia. In: Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; :295-318.

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.