Copy link

Sickle Cell Disease: Perioperative Management

Last updated: 08/14/2024

Key Points

- Patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) are at risk for vaso-occlusive events such as acute chest syndrome (ACS) and acute pain crises throughout the perioperative period.

- Perioperative management should involve a collaborative effort from the consultant hematologist, anesthesiologist, surgeon, and acute pain service to prevent complications associated with transfusion and postoperative pain.

- Efforts should be taken to minimize the risk of precipitating vaso-occlusive crises by avoiding hypoxemia, acidosis, hypothermia, dehydration, and excessive pain.

- This is part 2 of a two-part series that will review key aspects of the perioperative management of SCD. Please see Part 1 for a review of the pathophysiology, variants, and systemic effects of SCD.

Introduction

- SCD refers to a group of hemoglobinopathies characterized by the formation of long chains of hemoglobin when they become deoxygenated within capillary beds. This results in sickle-shaped red blood cells (RBCs), which in turn cause vaso-occlusion and, subsequently, multiorgan dysfunction.

- The complications of SCD result from two overlapping subtypes: vaso-occlusion and chronic hemolysis.

- Patients with SCD may experience recurrent episodes of one or more types of crises. These crises include severe pain crisis, ACS, priapism, aplastic crisis, and splenic sequestration. Other complications include pulmonary hypertension, chronic pain, kidney injury, avascular necrosis of the femur, strokes, leg ulcers, gallstones, etc.

- Surgery is associated with an increased risk of sickle-related complications such as ACS, pain crisis, stroke, and acute renal failure. Patients also have an increased risk of surgical complications such as infection and venous thrombosis. This summary will focus on the perioperative management of patients with SCD.

Preoperative Considerations

- Preoperative planning for patients who present for elective surgery should include input from the hematologist, anesthesiologist, surgeon, acute pain service, blood bank, and transfusion service. The multidisciplinary team should establish a plan for perioperative transfusion and pain management based on the patient’s baseline hemoglobin, expected blood loss, current pain regimen, and expected degree of postoperative pain.1

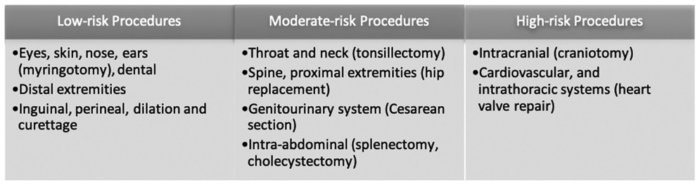

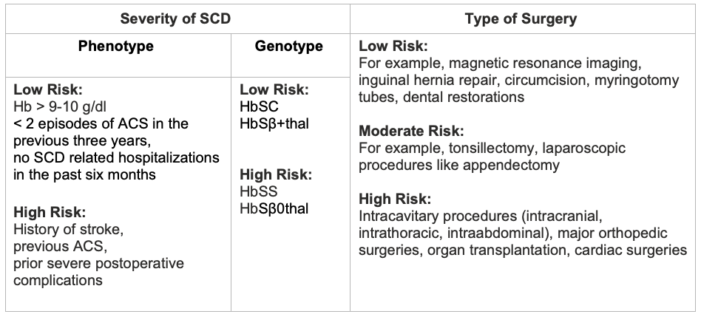

- Preoperative assessment should aim to determine the risk of perioperative SCD complications. The risk of complications is based on variables including type of surgical procedure (Table 1), severity of SCD, frequency of sickle cell complications, current organ dysfunction, and other comorbidities.1

Table 1. Risk stratification based on the type of surgery. Used with permission from Azbell RCG et al. Current evidence and rationale to guide perioperative management, including transfusion decisions, in patients with SCD. Anesth Analg. 2023.1

- A focused history should be taken to evaluate the patient’s baseline functional status, the severity of chronic pain, and the effects of SCD and its therapy on all systems, with an emphasis on neurologic, pulmonary, cardiac, and renal. A history of prior blood product transfusions, antigen and antibody detection, transfusion reactions, and alloimmunization is also very important. Preoperative laboratory workup should include a complete blood count, electrolytes, antibody screen, extended phenotyping, and cross-matching of packed RBC prior to surgery.1,2

- Preoperative transfusion decisions should be based on the patient’s baseline hemoglobin, comorbidities, and type of surgery.1 The prior history of packed RBC (PRBC) transfusions, transfusion reactions, and the presence of alloimmunization will play a role in making individualized transfusion decisions3 (see below).

- Efforts should be made to have patients scheduled early on the operating list to avoid prolonged starvation and dehydration, both of which can precipitate vaso-occlusive crises.

- Given the risk for severe complications, elective surgery should be delayed if the patient has a fever or signs of active vaso-occlusive crises.

- A thorough pain management plan should be established before surgery. Preoperative multimodal analgesia with nonopioid adjuncts (such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be used to reduce perioperative opioid consumption. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be used with caution in this patient population because SCD can result in acute and chronic renal dysfunction. When indicated, regional nerve blocks should be considered for postoperative pain control. Some patients may be on chronic opioids, and this will affect the postoperative pain management regimen.

- A multidisciplinary team comprised of the anesthesiologist, hematologist, and acute pain service should be involved in creating an individualized plan for postoperative pain control.

Preoperative Transfusion

- Surgery in patients with SCD is associated with an increased risk of ACS and painful vaso-occlusive crisis in the postoperative period.

- Preoperative transfusion is one of the commonly used optimization strategies because it helps to decrease vaso-occlusive crises by diluting the sickled RBCs and increasing the hematocrit.

- However, packed RBC transfusion in patients with SCD entails unique risks, listed below.

- Hyperviscosity: In patients with SCD, raising hemoglobin to greater than 11 g/dl can lead to vaso-occlusive complications due to increased viscosity.1

- Alloimmunization3

- It occurs when the immune system generates antibodies against minor blood group antigens found on donor RBCs, which are not present in the recipient’s cells.

- RBC alloimmunization is a serious and possibly life-threatening complication of transfusion in any chronically transfused patient. Two factors are thought to make SCD patients even more prone to alloimmunization. First, there is an antigen mismatch between the predominantly Caucasian donor pool and the predominantly African American recipient pool. Second, patients with SCD are in a chronic hyperinflammatory state, especially when they need transfusions.

- Alloimmunization increases the risk of life-threatening complications such as hyperhemolytic and delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions (DHTR).

- Alloimmunization makes it more difficult to find compatible RBCs for future transfusions.

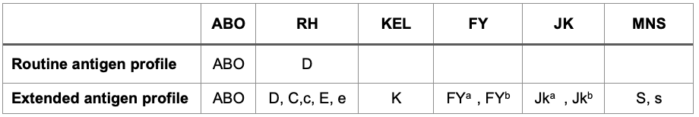

- To reduce this, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) recommends an extended recipient antigen profile test for at least the C, E, and Kell antigens to be done, ideally before the first transfusion, and donor RBCs to be chosen accordingly2 (Table 2).

Table 2. RBC antigen profile

-

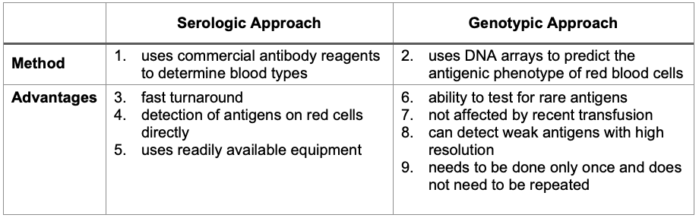

- The extended profile may be determined by serology or by genotyping, but genotyping is preferred (Table 3).

Table 3. Serologic and genotypic approaches to blood group antigen typing

DHTR and Hyperhemolytic Transfusion Reactions

DHTR2,4

- The ASH defines DHTR as a significant decrease in hemoglobin levels within 21 days of a transfusion, which is accompanied by an accelerated increase in HbS and a decrease in HbA. Reticulocytopenia and elevation in lactate dehydrogenase levels may also occur. Progression to multiorgan failure can occur with DHTR.

- DHTR can be difficult to diagnose in the SCD population because the symptoms mimic those of a vaso-occlusive crisis, including pain, fever, anemia, and hemoglobinuria.

- Some experts recommend checking total hemoglobin, HbS, and HbA levels within 48 hours after a transfusion so that a diagnosis of DHTR can be made should the patient develop signs and symptoms several days after the transfusion.

Hyperhemolysis

- Hyperhemolysis is a phenomenon in which the patient’s own RBCs undergo hemolysis after a transfusion, and the posttransfusion hematocrit may be lower than that before the transfusion.2,4

- Patients who receive transfusion in an urgent situation are at greater risk of developing hemolytic reactions.

- Immunosuppressive therapies like steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and/or rituximab may be administered for the prevention of hemolytic transfusion reactions in the following groups of patients:

- those who need a transfusion acutely;

- those at high risk for a hemolytic reaction; or

- those with a history of life-threatening or multiple DHTR.

- The ASH 2020 guideline for transfusion support for SCD suggests the same medications (steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and/or rituximab) and/or eculizumab for the treatment of DHTR and ongoing hyperhemolysis.2

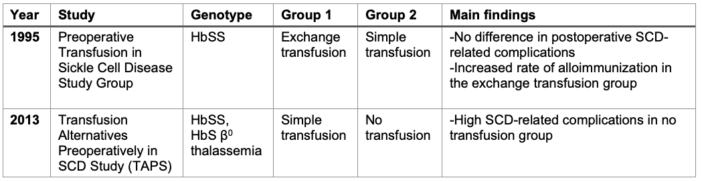

- Despite the increased risk of blood transfusion in SCD patients, numerous studies support its use in the perioperative period due to its efficacy in reducing the risk of developing ACS. Two landmark studies that contributed to this understanding are listed below (Table 4).

- A prospective observation study (Preoperative Transfusion in Sickle Cell Disease Study Group)5 from 1995 compared a conservative (simple transfusion aiming for Hb of 10 mg/dl) and an aggressive (exchange transfusion aiming for Hb of 10 mg/dl and HbS <30%) transfusion strategy. The study found no significant differences in postoperative ACS and painful crisis rates between the two groups. However, it identified an elevated risk of alloimmunization in the aggressively transfused group. The conclusion was that a conservative regimen provides comparable outcomes with fewer complications.

- Subsequently, a randomized controlled trial known as the Transfusion Alternatives Preoperatively in Sickle Cell Disease Study (TAPS)6 in 2013 aimed to compare preoperative transfusion (target Hb-10 g/dL) to no preoperative transfusion in low- and moderate-risk surgical procedures for patients with HbSS or HbSβ0 thalassemia. The study demonstrated an increased incidence of serious adverse events, particularly ACS, in the no-transfusion group, leading to the premature termination of the study. These findings further underscore the critical role of preoperative transfusion in mitigating risks associated with surgical procedures in SCD patients.

Table 4. Landmark studies on blood transfusion in SCD patients

- While the current evidence supporting preoperative transfusion is of low quality, the advantages of preventing postoperative ACS outweigh the potential risks.

- The ASH’s 2020 guideline for transfusion support in SCD patients suggests that patients undergoing surgeries lasting longer than one hour under general anesthesia may benefit from a simple PRBC transfusion.2

- However, there was a low level of certainty in making this recommendation, and there is still a controversy regarding the suitable preoperative transfusion regimen for patients with SCD.

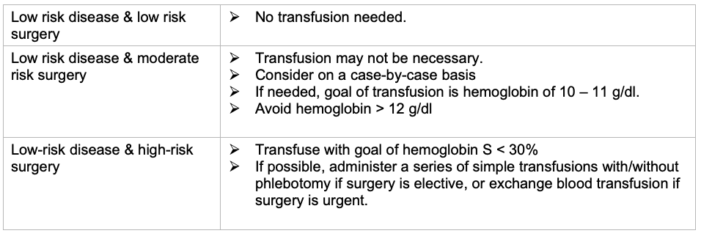

- The following factors must be considered when making the decision to transfuse a patient prior to surgery (Table 5):

- The risk level of surgery

- Baseline hemoglobin

- Severity of SCD

- Prior complications with transfusions

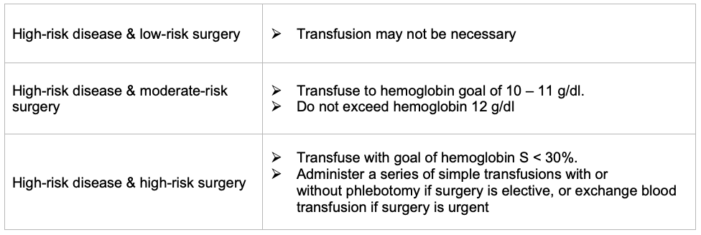

Table 5. Risk stratification based on disease severity and type of surgery

- Tables 6 and 7 summarize the different combinations of disease and surgery severity and management approaches that may be chosen.

Table 6. Plan for low-risk SCD. Adapted from Quality and Safety Corner—SPA Newsletter Summer 2022 & Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Newsletter June 2024.7,8

Table 7. Plan for high-risk SCD; Adapted from Quality and Safety Corner - SPA Newsletter Summer 2022 & Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Newsletter June 2024.7,8

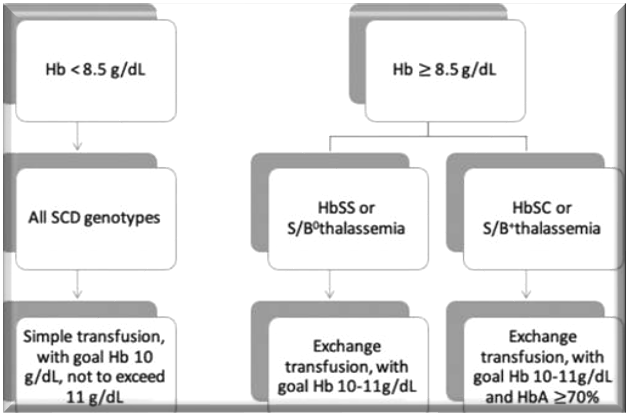

- For SCD patients with baseline hemoglobin below 8.5 g/dL, the suggested approach involves a simple transfusion with a target Hb goal of 10 g/dL, avoiding Hb greater than 11 g/dL to prevent hyperviscosity and potential vaso-occlusive crises, for surgeries lasting longer than an hour.1 (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Preoperative transfusion management in SCD patients. Used with permission from Azbell RCG et al. Current evidence and rationale to guide perioperative management, including transfusion decisions, in patients with SCD. Anesth Analg.1

- Collaboration with a hematologist familiar with the patient is advised when planning any surgical procedures for individuals with SCD.

Intraoperative Considerations

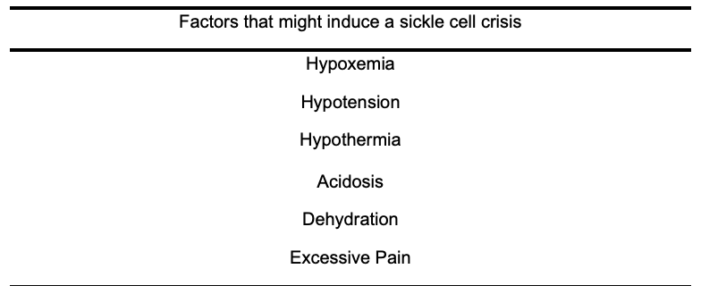

- The intraoperative phase places the patient at high risk of triggering sickling and vaso-occlusive events. Therefore, the primary objectives of care should focus on maintaining euvolemia and normothermia while avoiding hypoxemia, hypotension, and acidosis (Table 8).

Table 8. Factors that increase the risk of sickle cell crisis

Perioperative management should prioritize avoiding these precipitating events.1

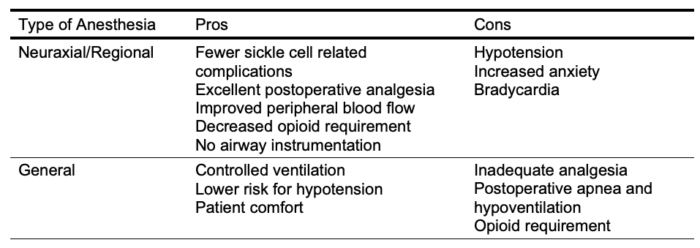

- The choice of anesthetic technique depends on considerations such as patient preference, surgical technique, and expectation of postoperative pain. Neuraxial anesthesia provides a sympathectomy and vasodilation that help lower the risk of sickle cell-related complications compared to general anesthesia. Both regional and neuraxial anesthesia provide superior analgesia (Table 9).

Table 9. Pros and cons of general anesthesia vs neuraxial/ regional anesthesia in SCD patients

- Patients with SCD have decreased renal function and impaired urinary concentrating ability, which can increase the risk of dehydration. This can result in intravascular volume depletion, increasing the risk of sickling and vaso-occlusive crisis. Conversely, excessive hydration poses an increased risk of pulmonary edema (especially in those with underlying cardiovascular disease) and an increased likelihood of ACS. Hence, careful fluid management is essential during the intraoperative phase, and opting for a balanced salt solution is a prudent choice.

- Ensure optimal oxygenation and normocarbia (if controlled ventilation) to decrease the risk of sickling.

- Cold temperatures can trigger a vaso-occlusive crisis. To maintain normothermia measures such as a warm operating room, the use of forced air heat blankets, and the administration of warm fluids are important.

- Patients on chronic opioids should continue their medications throughout the perioperative period to avoid the risk of withdrawal, wind-up pain, and postoperative hypoventilation secondary to excessive pain. Patients may require a patient-controlled analgesia technique postoperatively.

- Multimodal analgesia with nonopioid medications such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can help to reduce opioid consumption. Careful consideration is necessary with NSAIDS, given the risk of renal injury in SCD patients.

- Ketamine can also be used to help reduce opioid consumption. It can treat opioid tolerance in addition to reducing opioid-induced hyperalgesia.1

Tourniquet Use

- The use of tourniquets can increase the risk of sickling in the ischemic extremity.9 Tourniquets can also induce a sickle cell crisis because of the acid that enters the circulation upon deflation. In one report, the oxygen tension decreased from 45-24mmHg at 30 min to 20mmHg at 60 min and 4 mmHg at 120 min in the ischemic extremity. In an in vitro study, 90% of homozygous sickle cell RBCs demonstrated sickling at an oxygen tension of 25 mmHg. However, in RBCs with sickle cell trait, sickling occurred only when the oxygen tension decreased to 15mmHg.

- Most guidelines discourage the use of tourniquets in this population. However, tourniquets provide a bloodless surgical field, decrease the duration of surgery, and reduce blood loss, so they might be needed for certain procedures.

- There are no randomized, prospective studies on the use of tourniquets in patients with SCD or sickle cell trait. However, case reports and case series suggest that if used, the complications are not very common and can be managed.

- Adequate hydration and hyperoxygenation prior to tourniquet application might help optimize the chances of a good outcome. Careful and complete exsanguination of the extremity with an Esmarch bandage should be performed prior to inflation of the tourniquet. Inflation to higher pressures than necessary should be avoided.

- There are no specific recommendations regarding preoperative transfusion in the setting of planned tourniquet use for patients with SCD or sickle cell trait.

Cardiopulmonary Bypass

- Cardiac surgery, and especially cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), places patients with SCD under conditions that promote sickling of RBCs, such as hypothermia, cross-clamping, low flow, circulatory arrest, acidosis, and possible exposure to cold cardioplegia.10

- Being a major surgery in patients with SCD or sickle cell trait, guidelines suggest that HbS levels should be less than 30% prior to surgery. If hypothermia or cold cardioplegia will be employed, then a HbS level of about 10%-20% is reasonable. Other reasonable targets during CPB include oxygenating the circuit to a PaO2 greater than 375mmHg prior to and maintaining this level during surgery. Maintaining a venous oxygen saturation of 75%-80% and pH between 7.34-7.44 has also been suggested.10

- HbS levels less than 10-30% may be achieved with exchange transfusions prior to surgery. Alternatively, an exchange transfusion can be performed using the bypass circuit on the day of surgery.

- These patients often will need multiple transfusions and appropriately cross-matched products should be available.

Postoperative Considerations

- Following surgery, SCD patients are at increased risk of vaso-occlusive crises such as ACS, severe pain, acute kidney injury, stroke, and venous thromboembolism. Given this risk, they may require higher acuity units, as opposed to floor management, for postoperative recovery.

- Multidisciplinary care with the anesthesiologist, acute pain service, and hematologist is optimal. A hematologist should continue to follow the patient throughout their postoperative course to manage the need for transfusion and evaluate the patient for SCD-related complications.

- Postoperative pain should be managed based on the established multidisciplinary care plan. Opioids are considered a first-line agent for postoperative pain and should be administered based on the patient’s baseline opioid requirements and expected postsurgical pain. Adjuvant analgesics should be used judiciously to prevent respiratory depression and the likelihood of hypoxia.

- Oxygen saturations should be monitored continuously until it is maintained at baseline on room air. Supplemental oxygen should be administered as needed.

- Supportive care, such as early mobilization, physiotherapy, and incentive spirometry, is an important component of postoperative management. It helps prevent complications such as venous thromboembolism, wound infections, ACS, and acute and pulmonary infections.

References

- Azbell RCG, Lanzkron SM, Desai PC. Current evidence and rationale to guide perioperative management, including transfusion decisions, in patients with sickle cell disease. Anesth Analg. 2023;136(6):1107-14. PubMed

- Chou ST, Alsawas M, Fasano RM, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: transfusion support. Blood Adv. 2020;4(2):327-55. PubMed

- Yazdanbaksh K, Ware RE, Noizat-Pirenne F. Red blood cell alloimmunization in sickle cell disease: pathophysiology, risk factors, and transfusion management. Blood. 2021;120(3): 528-37. PubMed

- Fasano RM, Miller MJ, Chonat S, et al. Clinical presentation of delayed hemolytic transfusion reactions and hyperhemolysis in sickle cell disease. Transfus Clin Biol. 2019;26(2):94-8. PubMed

- Vichinzky EP, Haberkern CM, Neumayr L, et al. A comparison of conservative and aggressive transfusion regimens in the perioperative management of sickle cell disease. The preoperative transfusion in sickle cell disease study group. N Engl J Med. 1995; 33394): 206-13. PubMed

- Howard J, Malfroy M, Llewelyn C, et al. The transfusion alternatives preoperatively in sickle cell disease (TAPS) study: a randomized, controlled, multicentre clinical trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9870): 930-8. PubMed

- Baijal R, Dalal P, Kanjia M. What are the indications for preoperative blood transfusion and children with sickle cell disease? Society for Pediatric Anesthesia Newsletter Quality and Safety Corner. Summer 2022.35(2). Link

- Baijal R, Dalal P, Kanjia M. Preoperative Transfusion and Sickle Cell Disease in the Pediatric Patient. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Newsletter 2024. Link

- Pignatti M, Zanella S, Borgna-Pignatti C. Can the surgical tourniquet be used in patients with sickle cell disease or trait? A review of the literature. Expert Rev Hematol. 2017;10(2):175-182. PubMed

- Daaboul, DG, Yuki K, Wesley MC, et al. Anesthetic and cardiopulmonary bypass considerations for cardiac surgery in unique pediatric patient populations: sickle cell disease and cold agglutinin disease. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2011;2(3): 364-70. PubMed

Other References

- Ross F. Perioperative management of sickle cell disease. OA Ask the Expert Podcast. 2019. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.