Copy link

Pulmonary Aspiration

Last updated: 09/20/2023

Key Points

- Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents can lead to chemical irritation of the lung parenchyma in the first 1-2 hours, followed by an acute inflammation.

- Most aspiration events do not develop into bacterial pneumonia.

- Lung abscesses usually occur in patients with chronic aspiration.

Introduction

- Pulmonary aspiration pertains to the inhalation of substances from the oral cavity or upper gastrointestinal tract. The materials that can be aspirated range from physiological secretions such as saliva to more irritating substances such as toxins or gastric contents.

- Aspiration pneumonia is an umbrella term for the adverse pulmonary consequences from aspiration.1 It includes chemical pneumonitis and bacterial aspiration pneumonia.

- Chemical pneumonitis refers to the aspiration of substances (e.g., acidic gastric contents) that causes an inflammatory reaction in the lower airways, independent of bacterial infection.1

- Bacterial aspiration pneumonia refers to an active infection that results from inoculation of bacteria into the lungs via orogastric contents.1

- Aspiration is a common event, and it is estimated that as many as half of all adults aspirate during sleep, making it difficult to quantify the true rate of aspiration pneumonia.2

- Similarly, the outcomes of aspiration events can vary, from normal physiological responses to severe infectious complications.

- Chemical pneumonitis from aspiration was first described by Curtis Lester Mendelson in young and healthy obstetrical patients following aspiration of gastric acid under anesthesia and is sometimes referred to as Mendelson syndrome.3

- Conditions that predispose to aspiration include1

- Altered consciousness: seizures, alcoholism, head trauma, general anesthesia, drug overdose, etc.

- Neurological disorders: stroke, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, myasthenia gravis

- Advanced age

- Cardiac arrest

- Dysphagia: esophageal stricture, neoplasm, diverticula, achalasia, tracheoesophageal fistula, xerostomia, etc.

- Mechanical disruption of usual defenses: nasogastric (NG) tube, endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy, bronchoscopy, etc.

- Periodontal disease

- Others: gastric outlet obstruction, large volume NG tube feeds, recumbent position, gastroparesis, etc.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- Patients commonly present with:

- Tachypnea

- Tachycardia

- Decreased breath sounds

- Rales or diffuse crackles

- Fever or hypothermia

- Hypoxia/hypoxemia

- Cough with purulent sputum production

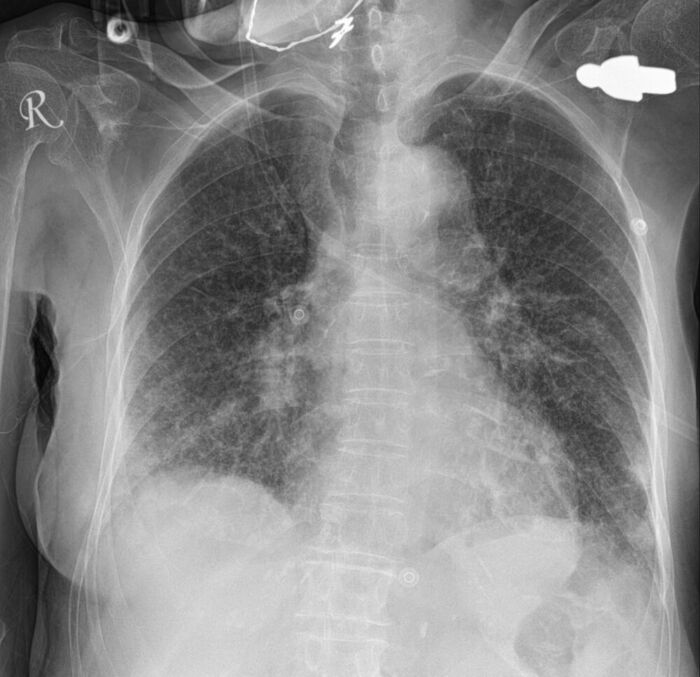

- Radiological findings can show infiltrates that are often, but not exclusively, in the dependent lung segments (Figures 1 and 2). In the setting of aspiration-related lung abscesses, cavitary lesions may be present.

Figure 1. Initial chest radiography (CXR) of a patient with suspected aspiration showing bilateral patchy infiltrates, mainly in the lower lobes. Source: Case courtesy of Bálint Botz, Radiopaedia.org. rID: 64251. Link.

Figure 2. Chest radiography (CXR) 3 days later showing improvement in the right lung. The left lung still has patchy infiltrates. Source: Case courtesy of Bálint Botz, Radiopaedia.org. rID: 64251. Link.

Pathogens

- In patients who develop aspiration pneumonia, common pathogens include respiratory flora such as S. pneumoniae or H. influenzae.

- In patients who are hospitalized or are coming from a nursing home, enteric gram-negative bacteria should also be considered in addition to respiratory flora.

Management

Immediate treatment

- In the event of pulmonary aspiration, immediate oropharyngeal suctioning should be performed. The patient should be placed in the Trendelenburg position with the head turned to the side to prevent further aspiration.1

- The patient should be intubated and the endotracheal tube should be suctioned. Bronchoalveolar lavage may be used to clear particulate matter.1

Treatment of Aspiration Pneumonitis

- Symptoms usually resolve in 24-48 hours with only supportive care that includes supplemental oxygen or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. In severe cases, intubation and invasive positive pressure ventilation may be required.

- Antibiotics are typically not indicated for most aspiration events despite radiographic findings suggesting aspiration or aspiration pneumonitis.

- Antibiotics should be considered if:

- patient is hemodynamically unstable;

- if symptoms last more than 48 hours; or

- there is another potential source of infection.

- The routine use of glucocorticoids for aspiration pneumonitis is not recommended.1

Treatment of Aspiration Pneumonia

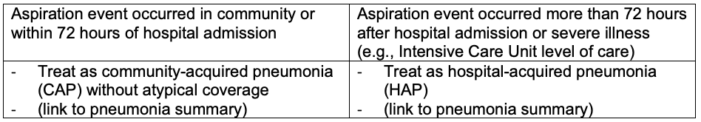

- The treatment of aspiration pneumonia is listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Treatment of aspiration pneumonia

- The Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines do not recommend adding anaerobic coverage for suspected anaerobic coverage beyond standard empiric treatment for community acquired pneumonia,4 although this is a conditional recommendation with a very low quality of evidence.

- The rationale includes:

- Older studies showed high isolation rates of anaerobic organisms, but more recent studies have shown anaerobes are uncommon in patients hospitalized with suspected aspiration.5,6

- With the increasing prevalence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens and complications of antibiotic use, antibiotic stewardship and careful consideration of therapies are warranted.

Special Considerations

- Postobstructive pneumonia can develop distal to a bronchial obstruction (e.g., malignancy).

- This is often due to accumulation of secretions rather than an acute infection.

- Discordance between organisms recovered using needle aspiration vs. recovered from sputum culture has been reported.7,8

- It should be treated as CAP or HAP depending on the severity of illness.

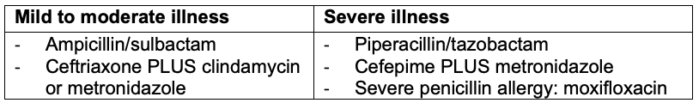

- Lung abscess/empyema

- Usually occurs in chronic aspiration and is often subacute

- Usually associated with periodontal disease and/or alcoholism

- Possible treatment regimens are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Antibiotics for lung abscess

References

- Klompas M. Aspiration pneumonia in adults. In: Post T (ed). UpToDate. 2023A. Link

- Gleeson K, Eggli DF, Maxwell SL. Quantitative aspiration during sleep in normal subjects. Chest. 1997; 111:1266–72. PubMed

- Salik I, Doherty TM. Mendelson Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Link

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7): e45-e67. PubMed

- El-Solh AA, Pietrantoni C, Bhat A, et al. Microbiology of severe aspiration pneumonia in institutionalized elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003; 167:1650–4. PubMed

- Marik PE, Careau P. The role of anaerobes in patients with ventilator associated pneumonia and aspiration pneumonia: a prospective study. Chest. 1999; 115:178–83. PubMed

- Liao WY, Liaw YS, Wang HC, et al. Bacteriology of infected cavitating lung tumor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000; 161:1750–3. PubMed

- Hsu-Kim C, Hoag JB, Cheng GS, et al. The microbiology of postobstructive pneumonia in lung cancer patients. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2013; 20:266–70. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.