Copy link

Provider and Patient Safety in Non-Operating Room Anesthesia Locations

Last updated: 12/04/2024

Key Points

- As technology in non-operating room anesthesia (NORA) locations has become more advanced, a larger proportion of anesthetics are being performed in the NORA environment.

- Patients in NORA locations have a higher mean age and a higher proportion of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status class III-V than patients in the operating room (OR).1

- Emergency preparation and closed-loop communication are essential in NORA locations due to the remote location and unfamiliar personnel. NORA safety time-out checklists are critical to achieving this and should be incorporated into every practice.

Definitions, Growth, and Scope of NORA

Overview of NORA

- NORA refers to the growing body of anesthesiology services provided in hospital-based and outpatient locations other than the traditional OR setting.

- These anesthetics are often defined by unique ergonomics and room layouts. For example, a case may involve large radiographic equipment during interventional radiology procedures with a difficult-to-access airway or a small procedural area in the electroconvulsive therapy suite.

- Because of these nuances, NORA cases require unique considerations, preparations, communications, and contingencies by the anesthesiologist, proceduralists, and nursing teams.

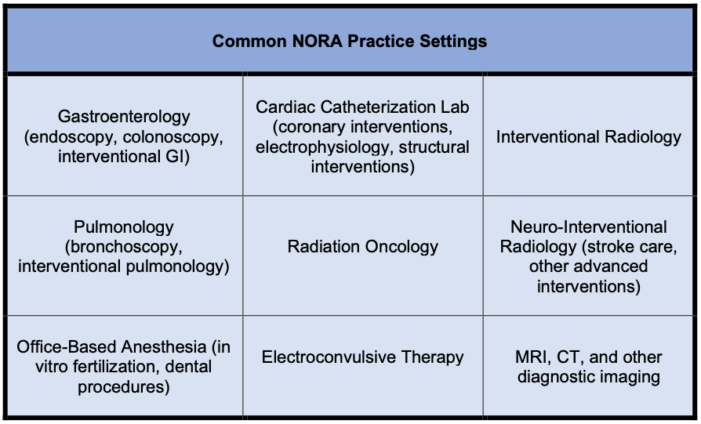

Common NORA Practice Settings (Table 1)

Table 1. Common NORA practice settings

Growth of NORA Services

- As technology in NORA locations has become more advanced, there has been a trend towards a larger proportion of anesthetics in the NORA environment.

- In the United States, NORA accounted for:1

- 28.3% of anesthetics in 2010

- 35.9% of anesthetics in 2014

- Projection: More than 50% of anesthetics within the next decade

- Therefore, it is imperative that all anesthesiologists receive the appropriate training to feel comfortable providing the same level of safe care in these less traditional spaces.

Unique Clinical Considerations in NORA

Patient and Procedure Characteristics

- Patients have a higher mean age and a higher proportion of ASA physical status class III-V compared to patients in the OR.1

- Older patients are more likely to have multiple comorbidities or be poor surgical candidates; therefore, these patients are often funneled to NORA interventions. Thus, preoperative evaluation and screening are essential.

- On average, the duration of NORA cases is about half as long as those in the OR. This creates a high turnover environment.

- NORA cases are more likely to be started later in the day, which may contribute to resource limitations for anesthesiologists.1

- Gastroenterology is the most frequent location for NORA procedures, with colonoscopy being the most frequent.

- Please see the OA summary on pediatric NORA for specific considerations in children. Link

Environmental Challenges

- Often, spaces are designed or retrofitted to hold equipment for specialized medical interventions, and the additional needs (anesthesia machines, gas supply lines) are not considered.

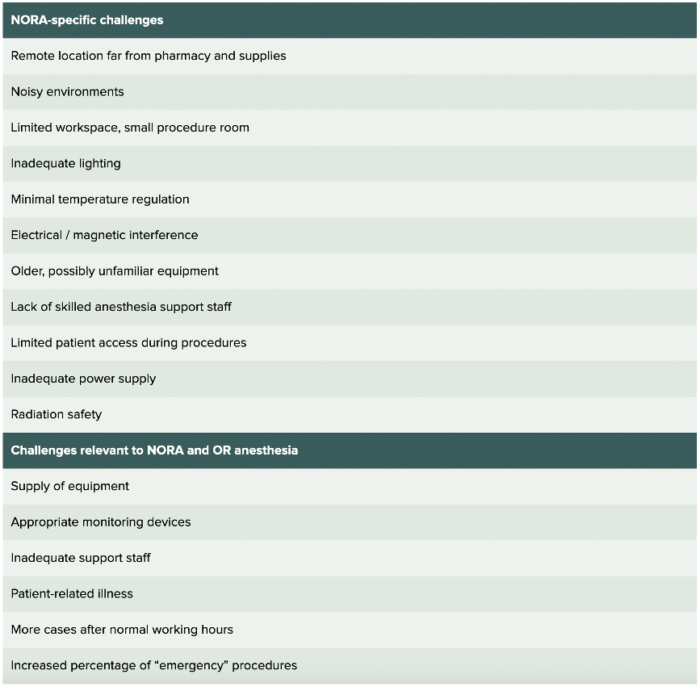

- NORA locations may have inadequate lighting (dark endoscopy room), temperature regulation, power supply, anesthetic equipment, drug supplies, or radiation safety equipment.2

- Ergonomic difficulties include small procedural rooms, limited workspace, excessive noise, and obstructions to the head of the patient.

- For example, an endoscopy suite can be as small as 180 sq. ft., with a fluoroscopy machine obstructing patient airway access.

- Remote locations can require the transport of a patient for a significant distance and being far away from backup assistance. NORA locations may be on the same or different floors from the ORs or in different facilities.3

Staffing

- A complex system of proceduralists, anesthesiologists, nursing staff, and administrators is needed for individual NORA locations. This system requires a unique patient flow consisting of preoperative screening, patient instructions, and disposition.

- Anesthesiologists are often unfamiliar with or weary of working outside the OR environment, necessitating a degree of specialization that can limit the flexibility of anesthetic care.

- Although there is an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement for an “offsite/NORA” rotation in residency, the training exposure and curriculum vary greatly across programs, further contributing to the unfamiliarity some anesthesia providers feel in NORA locations.

- With greater penetration of anesthesiology services in the NORA environment, proceduralists and nurses are unfamiliar with the needs of anesthesiologists and the basics of safe anesthesiology practice.

- NORA procedures are performed by consultants, who may not have as much background with their patients as primary care providers. This reality further highlights the need for thorough preoperative evaluation by the anesthesiology team.

Figure 1. Challenges to providing safe care in NORA setting. Reproduced with permission from the APSF. Walls JD, Weiss MS. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. APSF Newsletter June 2019.

NORA Emergency Preparedness and Response: The Importance of Safety Time-Outs and Checklists

Emergency Preparedness and Response

- Emergency preparation for patient safety events is of the utmost importance in NORA suites for reasons discussed above, namely, the often remote locations with limited resources and personnel combined with a complex patient population.3

- Closed-loop communication between the anesthesiology, procedure, and nursing teams is critical.

- Emergency contact numbers for additional providers and anesthesia technicians are essential when help is needed. This information should be readily available and easily visible to team members in an emergency.

NORA Safety Time Outs and Checklists

- While NORA safety time-out checklists may bear similarities to those of the OR, their adoption in procedural areas may be inconsistent and not as standardized as the OR.4

- NORA suites, setup, and environment may vary significantly (e.g., endoscopy vs. catheter lab), and these differences should be recognized and addressed as needed during the timeout (e.g., patient access during magnetic resonance imaging scan).

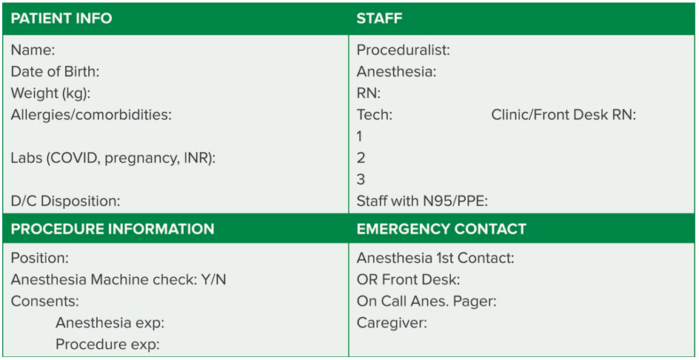

- Time-out checklists should ideally address concerns about the patient, procedure, team roles, and emergency response plan.4

- Everyone in the room should participate during the time-out to ensure patient, provider, and team safety.

- Figure 2 below is an example of a NORA timeout checklist that can be written on a whiteboard or projected on a screen.

Figure 2. NORA Time-Out Checklist: Reproduced and modified with permission from the APSF. Chang C, Dudley R. Time-out checklists promote safety in nonoperating room anesthesia (NORA). APSF Newsletter October 2021.36(3):120

References

- Nagrebetsky A, Gabriel RA, Dutton RP, Urman RD. Growth of nonoperating room anesthesia care in the United States: A contemporary trends analysis. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(4):1261-7. PubMed

- Walls JD, Weiss MS. Safety in non-operating room anesthesia (NORA). Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Accessed June 16, 2023. Link

- Beard J, Methangkool E, Angus S, et al. Consensus recommendations for the safe conduct of nonoperating room anesthesia: A meeting report from the 2022 Stoelting Conference of the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Anesth Analg. 2023;137(2):e8-e11. PubMed

- Chang C, Dudley R. Time-out checklists promote safety in nonoperating room anesthesia (NORA). Published October 2021. Accessed September 29, 2024. Link

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.