Copy link

Process Improvement

Last updated: 09/11/2024

Key Points

- Medical errors are largely prevented from harming patients due to barriers, recoveries, and redundancies in the healthcare system.

- The Anesthesia Incident Reporting System (AIRS) is a national reporting system for adverse anesthesia events created by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA).

- Debriefing is underutilized following adverse anesthesia events.

- Root cause analyses should look past unintentional human errors to identify system issues leading to adverse anesthesia events.

- Several implementation systems exist to improve safety and anesthetic quality, including the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle, Six Sigma, and Lean.

Introduction

- Anesthesiology is a field in which providers perform several complex tasks.

- Data collection is required in virtually every setting where anesthesia is delivered to keep patients safe and facilitate billing for medical services.

- As with other specialties, rapid improvements in data usage have given rise to formal processes, known as process improvement, by which medical systems can reduce errors and improve quality.

Medical Error

- Though anesthesia providers are vigilant by nature, eliminating the profession’s inherent risk and all errors from practice is unreasonable.

- Human errors in both manual and cognitive tasks occur several times daily within each anesthesia delivery system.

- No anesthesia provider, regardless of experience level, is immune to making an error.

- These errors are largely prevented from harming patients due to barriers, recoveries, and redundancies in the system that make the system in which providers work resilient.1

- Viewing errors as morally neutral and assessing the individual’s intention of harm before assigning blame creates a just work culture by which accountability is appropriately balanced between the individual and the system.1

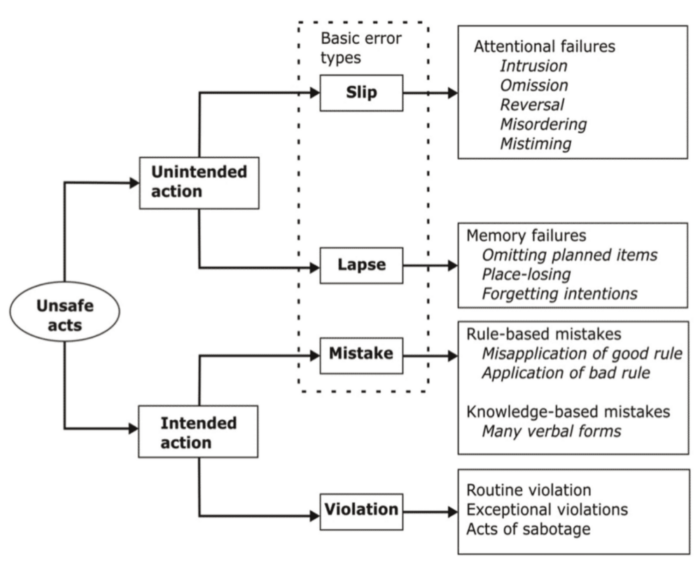

- Figure 1 illustrates possible error types based on intentionality.

Figure 1. Medical error types. Used with permission from Reason J. Human Error. Cambridge University Press. 1990 p 207.2

- The degree to which an error harms a patient ranges from no harm (“near miss”) to some harm (“preventable adverse event”) to severe harm or death (“sentinel event”).

- Because several near misses often precede preventable adverse events and sentinel events, it is essential to search for opportunities for improvement when any error is recognized. The process starts with reporting the adverse event.

Reporting Systems

- Adverse event reporting systems in anesthesiology exist from the institutional to national levels.

- Barriers to reporting include concerns about litigation, fear of disciplinary action, lack of support from colleagues, and not wanting to discuss the case in meetings.3

- Strategies to improve reporting include creating a supportive and just work culture, having senior role models, creating confidentiality, and affording legal protection for reported events.

- Institution-specific systems vary, but they should be confidential, include instructions on how to report and when to report, and provide timely feedback, including an action plan for reported events.

- These systems are essential in identifying issues requiring more extensive investigation and helping to compare and benchmark patient safety data over time and with other institutions.

National Reporting Systems in Anesthesiology

- The ASA created the Anesthesia Quality Institute (AQI) in 2008 “to be the primary source of information for quality improvement in the clinical practice of anesthesia”.4

- The AQI reporting system, which focuses on collecting data about adverse events, is the AIRS. AIRS reports can be made confidentially or anonymously, and reports are protected from use in legal proceedings.

- Adverse event reports can be made on the AQI website.

- The National Anesthesia Clinical Outcome Registry (NACOR) is the AQI reporting system focused on quality.

- NACOR tracks safety and value during anesthesia administration based on best-practice evidence.

- This allows participating groups to identify quality care gaps, negotiate reimbursement with insurance companies using data, and compare themselves to national benchmarks.

- The last ASA-funded reporting system related to patient safety is the Closed Claims Project, which started in the 1980s and works with malpractice insurance companies to review cases of adverse events involving anesthesiologists.

- All these national reporting systems help to demystify the practice of anesthesiology by recognizing ubiquitous complications to avoid and identifying quality benchmarks.

Debrief

- Once the adverse event is reported, a debrief is a helpful starting point toward process improvement. It should occur following any major adverse event in which a patient is harmed, whether preventable or non-preventable.

- Some indications for a debrief include intraoperative death, major intraoperative cardiopulmonary event, unanticipated difficult intubation, aspiration, significant drug error, equipment failure resulting in patient harm, surgical fire, wrong-sided nerve block, and wrong-sided surgery.

- The debrief is a reflective discussion of the actions and thought processes of the medical professionals involved in promoting learning and improving clinical performance.5

- The process should be confidential, respectful, and voluntary, occurring soon after the adverse event.

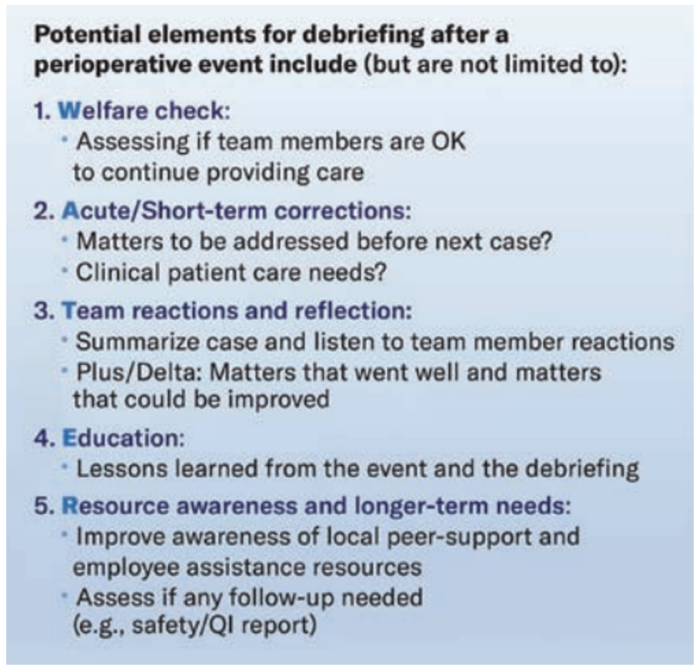

- Figure 2, from an ASA Monitor article, provides an example of elements to consider when debriefing.

Figure 2. Recommended elements of a debrief. Used with permission from Chen YK et al. Crisis checklists in emergency medicine: another step forward for cognitive aids. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2021; 30:689-93.6

- Literature about debriefing in anesthesiology is sparse.

- A recent single-center retrospective study suggests debriefing is underutilized and occurs less than 50% of the time following major adverse events, particularly when the adverse event contained a critical communication breakdown.7

- Another small study using debriefing in simulated emergency scenarios showed no significant improvement in the performance of the debriefed participants compared to the control group.8

- Finally, a large survey study found that the emotional toll on anesthesiologists following a major adverse event is high and that they were more likely to agree with statements about needing support following the event.9

- Following an adverse event or sentinel event in anesthesia, debriefing is likely an underutilized technique to mitigate the emotional and mental toll on the providers involved to potentially make the system safer.

Root Cause Analysis

- After the debrief, the next important step in preventing serious medical errors from reoccurring is a root cause analysis (RCA).

- The RCA team is encouraged to look past human errors, which are devoid of harmful intent, to identify systems issues that could have contributed to the adverse event.

- When an adverse event arises to the level of a sentinel event, organizations in the United States are strongly encouraged to report to the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) and are required to perform an RCA.11

- Sentinel event criteria identified by JCAHO include unexpected patient death, wrong site surgery, administration of blood causing severe harm, unintended retention of a foreign body, OR fire, and fall resulting in severe harm.

- The RCA and a corrective action plan must be completed within 45 days following the occurrence of a sentinel event for all JCAHO-accredited organizations, regardless of whether or not the event is reported.11

- Further information can be found in a separate root cause analysis summary.

Implementation Systems

- Implementation systems should be used as part of the action plan for an RCA or when performing quality improvement for identified systems issues.

- Several models, including the PDSA cycle, Six Sigma/Define-Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control (DMAIC), and Lean, have been used in anesthesia to improve safety and quality.

- The concept of Lean stems from the Toyota Production System and focuses on creating system efficiency by eliminating waste, inconsistency, and overburden.12

- Six Sigma focuses on decreasing variability in system processes using statistical analysis to find and fix specific issues. It uses the DMAIC method pictured below in Figure 3 to improve healthcare processes that have already been implemented.12

-

- In this method, the problem in the process is defined first, the whole process is measured, and the process is often analyzed using an RCA. Improvements are implemented to fix the root causes, and finally, controls are put in place so the interventions are sustained.

- By combining the elements of event reporting, debriefing, RCA, and implementing change, healthcare systems can continuously improve the process of anesthesia delivery and become more resilient to medical errors.

References

- Cohen JB. Achieving a successful patient safety program with implementation of a harm reduction strategy. APSF Newsletter. 2023; 38:93–95. Link

- Reason J. (1990). Human Error. Cambridge University Press. p 207. Link

- Heard GC, Sanderson PM, Thomas RD. Barriers to adverse event and error reporting in anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(3):604-14. Link

- AQI - Anesthesia Quality Institute. www.aqihq.org. Accessed April 16, 2024. Link

- Arriaga AF. Looking out for your colleagues: Real-time debriefing after critical events. ASA Monitor. 2021; 85:42–43. Listen

- Chen YK, Arriaga AF. Crisis checklists in emergency medicine: another step forward for cognitive aids. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2021; 30:689-93. Link

- Arriaga AF, Sweeney RE, Clapp JT, et al. Failure to debrief after critical events in anesthesia is associated with failures in communication during the event. Anesthesiology. 2019;130(6):1039-48. Link

- Morgan PJ, Tarshis J, LeBlanc V, et al. Efficacy of high-fidelity simulation debriefing on the performance of practicing anaesthetists in simulated scenarios. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103(4):531-7. PubMed

- Heard GC, Thomas RD, Sanderson PM. In the aftermath: Attitudes of anesthesiologists to supportive strategies after an unexpected intraoperative patient death. Anesth Analg. 2016;122(5):1614-24. PubMed

- Charles R, Hood B, Derosier JM, et al. How to perform a root cause analysis for workup and future prevention of medical errors: a review. Patient Saf Surg. 2016;10:20. Link

- Sentinel Event Policy (SE). Comp Accr Man for Amb Care. 2022. Link

- Barr E, Brannan GD. Quality Improvement Methods (LEAN, PDSA, SIX SIGMA). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.