Copy link

Prematurity

Last updated: 03/27/2024

Key Points

- Prematurity is classified by age from conception or birth weight.

- Prematurity is associated with many comorbidities of which the most common are necrotizing enterocolitis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and retinopathy of prematurity.

- The complications of prematurity can have anesthetic implications in the short and long term, including challenging venous access, pharmacologic dosing adjustments, and sometimes a need for prolonged respiratory support.

Introduction

- Prematurity is defined as an infant born prior to 37 weeks or 259 days of gestation.

- Prematurity can be classified by age from conception.

- Late (34 to <37 weeks)

- Moderate (32 to 34 weeks)

- Early (28 to 32 weeks)

- Extreme (<28 weeks, also known as micro-premies).1

- Prematurity may also be classified by birth weight.

- Low birth weight (< 2500 grams)

- Very low birth weight (< 1500 grams)

- Extremely low birth weight (< 1000 grams)

- Maternal risk factors for preterm birth can be demographic or obstetric/gynecologic in nature.2

- Demographic risk factors in the mother include but are not limited to:

- Older age

- Race and ethnicity: non-Hispanic, Black women’s risk is 50% higher than that of non-Hispanic, White, or Hispanic women’s risk of having a premature baby.3

- Smoking

- High body mass index

- Depression or anxiety

- Poverty and/or low education level

- Obstetric risk factors include but are not limited to:

- Short interval between pregnancies (<18 months)

- Prior preterm delivery

- Uterine surgical history (i.e., cesarean section or curettage)

- Uterine abnormalities (i.e., fibroids, uterine septum)

- Cervical conditions (short cervix)

- Demographic risk factors in the mother include but are not limited to:

Prematurity Associated Morbidities

- Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), also known as respiratory distress syndrome, is a chronic lung disease of prematurity that requires supplemental oxygen beyond 28 days after birth.4

- Premature infants are deficient in type 2 alveolar pneumocytes due to lung immaturity and have less surface area for gas exchange, decreased lung compliance, and loss of functional residual capacity.

- This manifests as tachypnea, grunting, nasal flaring, chest wall retractions, and accessory muscle use.

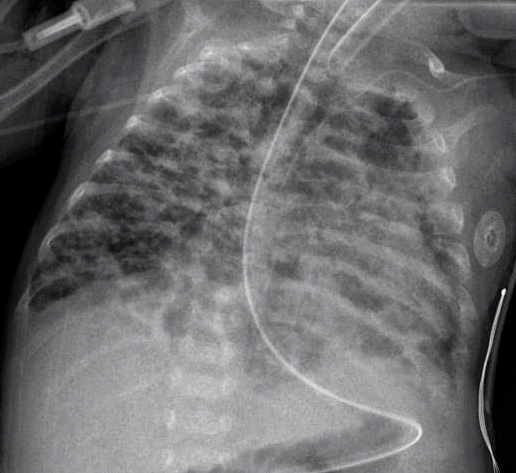

- A chest x-ray will display a “ground glass” appearance, an arterial blood gas (ABG) will demonstrate hypercarbia, hypoxemia, and respiratory acidosis, and there will be a substantial V/Q mismatch (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Radiograph of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (Source: Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED)

-

- Initial treatment includes supplemental oxygen with an arterial oxygen (PaO2) target between 55 and 70 mmHg and O2 saturation between 90-94%.

- Early and aggressive use of continuous positive pressure support via nasal continuous positive airway pressure is recommended to maintain oxygenation.4

- Inability to maintain PaO2 of 50 mmHg on 100% O2, a pH persistently < 7.2, or apnea unresponsive to pharmacotherapy may require mechanical ventilation with permissive hypercapnia, minimized inspired oxygen concentrations, and smaller tidal volumes.

- Hypoxia can increase the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis and mortality, while iatrogenic hyperoxia can result in an increased risk of developing retinopathy of prematurity. See ROP for more details.

- Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is associated with the disruption or arrest of neurovascular growth within the immature retina in prematurely born neonates and can be characterized by two phases.5

- Phase 1: Normal retinal vessels are arrested prematurely, which results in revascularized areas in the retinal periphery.

- Phase 2: Neovascularization/abnormal vascular growth occurs in the devascularized area. The new growth areas have increased risk of hemorrhage and edema, which results in scarring and potential blindness.

- Risk factors for the development of ROP include:6

- Prematurity (inversely related to gestational age)

- Low birth weight (inversely related to birth weight)

- Hyperoxia and need for supplemental oxygen

- Need for mechanical ventilation

- Hypoglycemia/increased use of exogenous glucose

- Infection

- Postnatal hypotension

- The risk of ROP can be reduced by carefully titrating the inspired concentrations of oxygen when supplementation is required.7

- Mild to moderate disease may resolve without intervention but advanced disease may require the following treatment options.

- Laser photocoagulation (most common, least side effects)

- Cryotherapy to the avascular retina

- Scleral buckling surgery with or without vitrectomy (for severe disease)

- Injection of antivascular endothelial growth factor antibodies and vitrectomy

- Long-term follow-up into adulthood is necessary, especially in moderate to severe cases of ROP.

- Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is a disease of the bowel that leads to a breakdown of the bowel wall and ultimately to bowel necrosis.8 (see Figures 2 and 3)

- NEC is seen in 5-11% of premature and low birth weight infants and causes 10-50% mortality.

- The cause is not well understood, is multifactorial, and relates to a lack of fully developed bowel, alterations in normal bowel flora, and bowel inflammation.

- Physical exam findings can be divided into early and late symptoms.

- Early symptoms include bradycardia, poor oral intake, temperature irregularity, apnea, lethargy, bloody stools, and mild abdominal distension.

- Late and severe symptoms include tachycardia, hypotension, acidosis, moderate abdominal distension, and peritonitis with or without sepsis.

- Xray findings include ileus, dilated bowel loops, and pneumatosis intestinalis, which is pathognomonic for NEC.

- Initial therapy is conservative and requires bowel rest, gastric suction for decompression, broad-spectrum antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, and correction of metabolic and electrolyte derangements.

- Vasopressor support is often needed, as well as prolonged ventilation as cardiac and respiratory failure can occur. In severe cases, premature neonates require urgent exploratory laparotomy, possible bowel resection and even massive volume and blood resuscitation.

- Complications include hypotension requiring vasopressor support, hemorrhage, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, multisystem organ failure, need for surgery, bowel resection, and death.

Figure 2. Bowel inflammation and necrosis in NEC; Photo Credit Dr. Douglas Katz, Cooper University Hospital, Camden, NJ

Figure 3. Bowel necrosis and pneumatosis intestinalis in NEC; Photo Credit Dr. Douglas Katz, Cooper University Hospital, Camden, NJ

Anesthetic Implications of Prematurity

- Prematurity impacts pharmacologic principles in multiple ways.

- Liver metabolism, renal excretion, and protein binding are all reduced from baseline.

- Increased total body water results in an increased volume of distribution.

- The combination of reduced metabolism/excretion and increased volume of distribution results in higher doses early on that need to be titrated to effect in smaller doses.

- In addition to a detailed review of the medical history, physical exam and supporting data, the following additional considerations should be made in the preoperative period.

- All electrolytes should be reviewed and corrected. Volume status and glucose requirements should be assessed.

- Complete blood count should be reviewed to ascertain presence of anemia and thrombocytopenia and ensure the availability of blood products, if needed.

- A cardiac exam should be performed, and any cardiology consultation/recommendations should be reviewed in the event there is concomitant congenital heart disease.

- If intubated, ventilatory support parameters, imaging and ABG trends should be reviewed and followed closely.

- Because venous access can be challenging, necessary venous access should be obtained ahead of time.

- Intraoperative considerations include the following.9,10

- Maintenance of core temperature by warming the environment, using additional warming devices, and measuring core temperatures

- Cautious mask ventilation, specifically to avoid insufflation of air into the abdominal cavity, which may lead to abdominal competition to ventilation

- Availability of video laryngoscopy and other difficult airway adjuncts for intubation, if not already intubated

- Continuation of preoperative glucose-containing fluids with regular glucose monitoring to prevent hypo- or hyperglycemia

- Measurement of urine output if large fluid shifts are expected

- Postoperative considerations include the following.

- Accommodations for the risk of postoperative apnea in the prematurely born infant (details addressed in a separate summary) Link

- Possibility of postoperative intubation and transport directly to the neonatal intensive care unit after major surgeries

References

- Glass HC, Costarino AT, Stayer SA, et al. Outcomes for extremely premature infants. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(6):1337-51. PubMed

- Cobo T, Kacerovsky M, Jacobsson B. Risk factors for spontaneous preterm delivery. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020; 150(1):17-23. PubMed

- Johnson JD, Green CA, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Racial disparities in prematurity persist among women of high socioeconomic status. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2(3):100-4. PubMed

- Sweet DG, Carnielli V, Greisen G, et al. European consensus guidelines on the management of respiratory distress syndrome: 2022 update. Neonatology. 2023;120(1):3-23. PubMed

- Cayabyab R, Ramanathan R. Retinopathy of prematurity: therapeutic strategies based on pathophysiology. Neonatology. 2016;109(4):369-76. PubMed

- Fagerholm R, Vesti E. Retinopathy of prematurity – from recognition of risk factors to treatment recommendations. Duodecim. 2017;133(4):337-44. PubMed

- McCann ME, Lee JK, Inder T. Beyond anesthesia toxicity: Anesthetic considerations to lessen the risk of neonatal neurological injury. Anesth Analg. 2019; 129(5):1354-64. PubMed

- Spaeth JP, Lam JE. The extremely premature infant (micropremie) and common neonatal emergencies. In: Cote CJ, Lerman J, Anderson BJ. A practice of anesthesia for infants and children. 6th edition. Philadelphia, PA; Elsevier; 2019: 841-67

- Macrae J, Ng E, Whyte H. Anaesthesia for premature infants. BJA Educ. 2021;21(9):355-63. PubMed

- Subramaniam R. Anaesthetic concerns in preterm and term neonates. Indian J Anaesth. 2019;63(9):771-79. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.