Copy link

Pierre Robin Sequence

Last updated: 01/12/2023

Key Points

- Patients with Pierre Robin sequence (PRS) often have associated anomalies or syndromes.

- Both mask ventilation and laryngoscopy are often difficult in patients with PRS.

- Physicians should limit direct laryngoscopy attempts in patients with PRS and introduce alternative intubation techniques early.

Introduction

- As described by Dr. Pierre Robin in 1923,1,2 PRS refers to the clinical triad of:

- micrognathia (small, symmetrically receded mandible);

- glossoptosis (downward and backward displacement of the base of the tongue);

- and airway obstruction.

- Although a cleft palate is common (up to 90% of cases), it is not required for the diagnosis.2

- The primary pathogenetic event that leads to PRS is unknown but generally accepted to be micrognathia causing upward and posterior displacement of the tongue, preventing closure of the palatine shelves before the 10th week of gestation.2

- PRS is termed a sequence because one anomaly (micrognathia) leads to a sequential chain of events causing the other anomalies.3 In clinical syndromes, a set of anomalies arise separately due to a common underlying pathogenesis.

- Incidence of PRS ranges from 1:5000 to 1:85,000 secondary to tremendous heterogeneity in clinical presentation and lack of uniform diagnostic criteria.1,2

- Although no clear genetic abnormality has been identified, the etiology of the micrognathia may be different for syndromic and nonsyndromic PRS. More than half of PRS newborns have an associated syndrome, chromosomal abnormality, or other additional anomalies.2

- More than 40 clinical syndromes have been associated with PRS.2

- Most common: Stickler syndrome, velocardiofacial (22q, 11.2 deletion, DiGeorge) syndrome.

- Less common: skeletal dysplasias, dysmorphic monogenic conditions such as Treacher-Collins syndrome, intrauterine exposures such as fetal alcohol syndrome, and maternal diabetes.

Clinical Presentation

- There is wide variability in the clinical presentation depending on the degree of micrognathia and airway obstruction. Obvious airway anomalies include a small chin and cleft palate (Figure 1).

- Breathing difficulty is secondary to partial (retraction, stridor, stertor) or complete airway obstruction that may be severe enough to require endotracheal intubation.

- Feeding difficulty: PRS patients are unable to coordinate suck and swallow and breathing due to airway obstruction and/or concomitant cleft palate. This often does not resolve with correction of airway obstruction and leads to failure to thrive without intervention.

Figure 1. Neonate with PRS. Source: Bütow KW, Zwahlen RA, Morkel JA et al. Pierre Robin sequence: Subdivision, data, theories, and treatment - Part 1: History, subdivisions, and data. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2016 Jan-Jun; 6(1): 31–34. CC BY SA 3.0.

- Prenatal diagnosis is based on the detection of micrognathia on ultrasonography and maternal polyhydramnios. Advanced imaging (fetal magnetic resonance imaging) allows calculation of jaw index and referral to a tertiary care center.

Evaluation and Medical Management

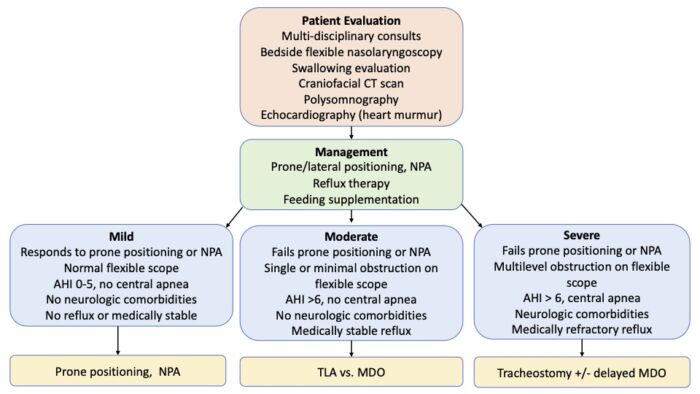

- Patients with PRS should be admitted to the neonatal ICU for further evaluation and management (Figure 2).

- A multidisciplinary consultation should include neonatology, craniofacial/plastics, otolaryngology, genetics, nutrition, speech pathology, and occupational therapy.2

- A flexible nasolaryngoscopy is often performed at the bedside to evaluate the degree of airway obstruction. A micro laryngoscopy/bronchoscopy in the operating room may also be considered.

- Relieving the airway obstruction is a priority.2 Options include:

- prone positioning which allows the mandible and tongue to fall forward, thereby reducing airway obstruction;

- nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) or distal end of a modified endotracheal tube placed intranasally and positioned in the distal oropharynx;

- endotracheal intubation and tracheostomy.

- A fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) is commonly performed, and if needed, supplemental feeding may be administered via a nasogastric tube.

- Gastroesophageal reflux therapy should be initiated, and the presence of associated anomalies and syndromes should be ruled out.

Figure 2. Clinical care pathway for the evaluation and management of patients with PRS. Abbreviations: NPA = nasopharyngeal airway, AHI = apnea-hypopnea index, TLA = tongue lip adhesion, MDO = mandibular distraction osteogenesis. Adapted from Cladis F, et al. Anesth Analg. 2014.2

Surgical Management

- Surgeries to relieve airway obstruction include:1,2

- Glossopexy (tongue-lip adhesion) is decreasing in popularity and involves anchoring the anterior tongue to the lower lip and the posterior tongue to the mandible. It is typically “taken down” before a year of age.

- Mandibular distraction osteotomy (MDO) involves bilateral mandibular osteotomies and placement of distraction devices that are gradually distracted (1-2 mm/day).

- Tracheostomy is reserved for patients with severe multilevel airway obstruction, those who fail other surgical interventions, the presence of syndromic PRS, or neurologic comorbidities such as central apnea.

- Other common surgeries performed in patients with PRS include palatoplasty, gastrostomy tube placement, Nissen fundoplication, dental and orthodontic procedures.

Anesthetic Considerations and Management

- Airway obstruction in patients with PRS may occur at multiple levels, including oropharyngeal obstruction from glossoptosis to hypopharyngeal obstruction secondary to the collapse of the epiglottis and base of the tongue (EBT).2 In addition, laryngomalacia, subglottic or tracheal pathology may also be present.

- In nonsyndromic PRS, there is often catch-up growth of the mandible, and the airway obstruction improves with age. This is not necessarily the case in syndromic PRS.

Preoperative Evaluation

- A detailed birth history, APGAR scores, apnea/cyanotic episodes or feeding difficulties in the early neonatal period should be obtained.2

- The clinician should enquire about the need for prone positioning.

A focused physical examination of airway should be performed, including the degree of micrognathia, presence of cleft palate, glossoptosis, airway obstruction in different positions, presence of heart murmur, etc. - The presence of associated anomalies or syndromes should be ruled out.

- The results of flexible nasolaryngoscopy should be reviewed, which is often performed at the bedside to identify the presence of patent choanae, degree of oropharyngeal obstruction, EBT collapse, laryngeal abnormalities, etc.2

- Previous airway management techniques should be reviewed, if applicable, such as difficulty with mask ventilation, intubation, what technique worked, etc.

- Diagnostic studies should be reviewed: CT craniofacial skeleton, polysomnography, echocardiography (if heart murmur present), etc.

Preoperative Set-Up

- The availability of difficult airway equipment should be ensured, including an assortment of NPAs, supraglottic airways (SGA), video laryngoscope, flexible bronchoscope, etc.

- Requesting the presence of the ENT surgeon and an additional anesthesiologist during induction should be considered.

Induction

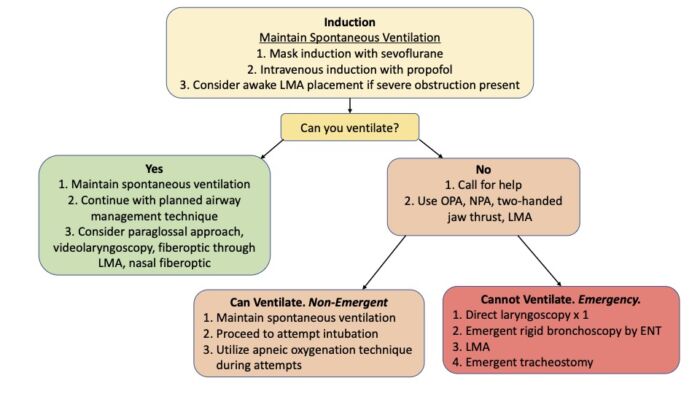

- A variety of airway management techniques have been used successfully in patients with PRS.2 These have been performed with minimal sedation, no sedation, or following induction of general anesthesia. Regardless of the approach, maintaining spontaneous ventilation is critical.

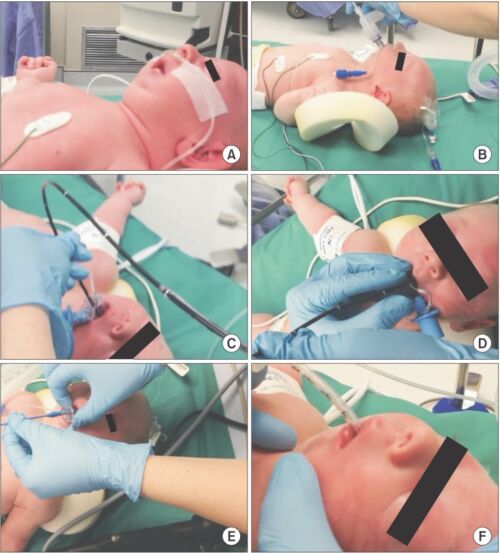

- An algorithm for the airway management of patients with PRS is shown in Figure 3. Fiberoptic intubation through an SGA is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Algorithm for airway management in patients with PRS. Abbreviations: OPA = oropharyngeal airway, NPA = nasopharyngeal airway, LMA = Laryngeal Mask Airway. Adapted from Cladis F, et al. Anesth Analg. 2014.2

Figure 4. Steps of fiberoptic intubation through an SGA in an infant with PRS. (A) PRS infant prior to induction; (B) Laryngeal mask airway (LMA) Classic™ inserted awake; (C) Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope (FFB) placed through Air-Q® 1.0; (D) Endotracheal tube (ETT) placed over FFB with patient induced and relaxed; (E) Air-Q® Pusher used to remove Air-Q®; (F) ETT in place.4

Maintenance and Emergence

- General anesthesia is typically maintained with a volatile anesthetic and can be supplemented with opioid and alpha-2 agonist (dexmedetomidine) infusions.2

- If tracheal extubation is planned, the patient must be fully awake before extubation.

- Most patients with PRS undergoing MDO remain intubated postoperatively for a few days while the MDO device is gradually distracted.

Postoperative Concerns

- Airway obstruction is the primary concern in the postoperative management of patients with PRS. These patients are very sensitive to opioids secondary to chronic hypoxemia and are at an increased risk for postoperative respiratory complications.2

References

- Evans KN, Sie KC, Hopper RA, et al. Robin sequence: from diagnosis to development of an effective management plan. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):936-48. PubMed

- Cladis F, Kumar A, Grunwaldt L, et al. Pierre Robin Sequence: a perioperative review. Anesth Analg. 2014;119(2):400-412. PubMed

- Diana Baxter D, Shanks AL. Pierre Robin Syndrome In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Link

- Templeton TW, Bryan YF. A two-stage approach to induction and intubation of two infants with Pierre Robin Sequence using an LMA Classic™ and Air-Q®: two case reports. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2016;69(4):390-4. CC BY NC 4.0. PubMed

Other References

- Video: Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing in a newborn with PRS. From: Cladis F, Kumar A, Grunwaldt L, et al. Pierre Robin Sequence: a perioperative review. Anesth Analg. 2014;119(2):400-412. Link

- Video: Airway obstruction in a neonate with PRS. From: Cladis F, Kumar A, Grunwaldt L, et al. Pierre Robin Sequence: a perioperative review. Anesth Analg. 2014;119(2):400-412. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.