Copy link

Pharmacological Changes with Aging: Inhalational and Intravenous Anesthetics

Last updated: 01/27/2023

Key Points

- Elderly patients have increased sensitivity to volatile anesthetics. The minimum alveolar concentration (MAC) required to produce anesthesia decreases by about 6% per decade.

- Elderly patients have increased body fat and decreased lean body mass, muscle mass, and total body water, which results in the accumulation of lipid-soluble volatile anesthetics. This results in increased body stores of anesthetics, which can potentially prolong emergence.

- The effects of propofol are more pronounced in elderly patients, resulting in higher plasma levels, increased sensitivity, and decreased drug clearance. Dosing of propofol infusions and boluses should be adjusted accordingly to avoid prolonged recovery times.

- Etomidate is considered the induction agent of choice in elderly patients, especially those with cardiac disease, due to a minimal reduction in systemic vascular resistance (SVR), and no effect on myocardial contractility, heart rate (HR), and cardiac output (CO).

- Due to its sympathomimetic effects, ketamine should be used with caution in elderly patients, especially those with coronary artery disease (CAD). However, it may be of use in elderly patients with reactive airway disease or hemodynamic compromise caused by hypovolemia or cardiomyopathy (in the absence of CAD).

Introduction

- It is important to differentiate between normal physiological changes with aging and pathologic states such as atherosclerosis. While increased age is a risk factor for many pathologies, not all aging adults develop pathologic changes. In this summary, we will focus on the pharmacological issues associated with normal physiologic aging and not with pathologic changes that may occur with aging.

Volatile Anesthetics

- Volatile anesthetics have altered pharmacokinetics in elderly patients for multiple reasons. Elderly patients have:

- decreased total body weight and lean body mass;

- increased percentage of body fat (by 50-70%);

- decreased total body water, and;

- increased solubility of volatile anesthetics.

- These changes result in an increased volume of distribution.

- Decreased hepatic function and decreased pulmonary gas exchange secondary to lower metabolic rate may also decrease anesthetic clearance. Decreased CO in certain older adults with heart disease decreases tissue perfusion, increases tissue time constants, and may also be associated with an altered regional distribution of anesthetics.1

- These changes lead to more accumulation of lipid-soluble volatile anesthetics, thereby prolonging emergence.2

- There is no change in the blood-gas solubility of volatile anesthetics with aging.3 However, postmortem studies have shown that tissue solubility increases with aging.

- Of the currently used volatile anesthetics, sevoflurane undergoes the greatest amount of hepatic metabolism via cytochrome P450 2E1 to produce fluoride ions. This had previously been thought to cause subclinical renal impairment, but multiple studies have failed to support this finding. While elderly patients have impaired renal function, none of the volatile anesthetics have been shown to cause renal impairment.3

- While age-related ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch could theoretically influence the uptake of volatile anesthetics, there is currently no strong evidence that demonstrates an age-related decrease in alveolar gas-exchange surface area, and V/Q mismatching significantly influences volatile anesthetic uptake.2 However, elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or emphysema may have a slower increase in the alveolar concentration of volatile agents.4

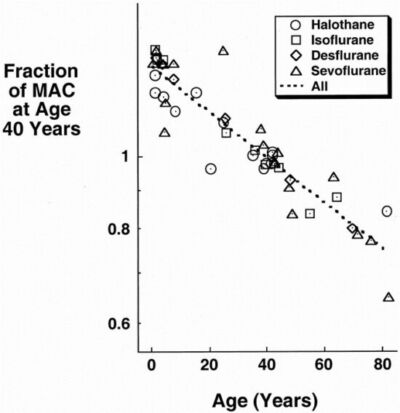

- Volatile anesthetics show increased potency with aging. MAC decreases by about 6% per decade after the age of one year.2 (Figure 1) Data from emerging studies indicates that the slope of the MAC decline is log-linear rather than purely linear.5

- Nitrous oxide was previously thought to be associated with an increased incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction (MI) and delirium in elderly patients.6 The ENIGMA trial showed that nitrous oxide use was associated with an increased long-term risk of MI but not death or stroke.7

- While receiving any inhaled anesthetic is associated postoperative cognitive dysfunction, studies have failed to show any difference between the various agents.8

Figure 1. A plot of the normalized ratios obtained by dividing the MAC at a particular age by the MAC at age 40 years. Reproduced with permission from Eger EI, Age, minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration, and minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration awake. Anesth Analg. 2001;93(4): 947-53.9

Propofol

- Administration of a large bolus of propofol may result in hypotension and lower the mean arterial pressure (MAP), therefore lowering the cerebral perfusion pressure.

- With increasing age, changes in the brain result in a relative increase in the potency of propofol. As measured by electroencephalography suppression, geriatric patients are 30% more sensitive to the effects of propofol, when compared to younger patients.9 Therefore, the bolus dose of propofol should be decreased by 40-50% to 1-1.75 mg/kg.

- The context-sensitive half-time of propofol also increases with age. Therefore, the maintenance dose of propofol infusion should also be decreased by 30-50% to avoid prolonged recovery times.

- For example, a 75-year-old patient requires only half of the maintenance infusion that a 25-year-old patient would need.10 The context-sensitive half time is ~ 20-30 mins after a 1–2-hour infusion in elderly patients, compared with 10-15 mins in younger patients.10

- In conclusion, the altered pharmacokinetics are best counteracted by administering a reduced dose of propofol for induction (by 40-50%), slower induction (over 30 sec), and preadministration of a vasoconstrictor (such as phenylephrine) to counteract hypotension that may result.11

- Age-associated decreases in renal function and glomerular filtration rate are associated with decreased propofol clearance.12

- The closing capacity of the aging lungs eventually exceeds functional residual capacity, causing apneic patients to desaturate faster than their younger counterparts. This should be taken into account when administering propofol boluses due to the resulting apnea. Elderly patients also have a decreased cough reflex and therefore, are less able to clear their secretions. This impairment is further worsened by propofol administration, which blunts the airway reflexes and could potentially increase aspiration risk in elderly patients.11

Etomidate

- While both propofol and etomidate act at gamma amino butyric acid receptors, elderly patients do not display the increased sensitivity to etomidate that is seen with propofol administration.4 Thus, any alterations in the dosing of etomidate in elderly patients are due to changes in the pharmacokinetics and not pharmacodynamics.

- Etomidate is considered the induction agent of choice in elderly patients due to minimal reduction in SVR and no effect on myocardial contractility, HR, and CO. This makes etomidate the induction agent of choice in elderly patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases such as compromised intravascular stents, CAD, or poor ventricular function.13

- Decreased volume of distribution and diminished clearance result in higher plasma levels of etomidate in elderly patients.13

- Due to the altered pharmacokinetics of etomidate in elderly patients, the induction dose should be decreased from 0.3-0.4 mg/kg to 0.2 mg/kg.

Ketamine

- The dose of ketamine should be decreased in elderly patients with kidney dysfunction due to the dependence on renal excretion of an active metabolite, norketamine.11 For elderly patients with normal creatinine clearance, there is little to no evidence to suggest that the dose of ketamine should be modified.

- Ketamine exhibits sympathomimetic effects, resulting in tachycardia, increased systemic and pulmonary artery blood pressure, and increased cardiac output. Thus, ketamine should be used with caution in elderly patients, particularly those with coronary artery disease.13

References

- Strum DP, Eger EI 2nd, Unadkat JD, et al. Age affects the pharmacokinetics of inhaled anesthetics in humans. Anesth Analg. 1991;73(3): 310-8. PubMed

- Sadean MR, Glass PSA. Pharmacokinetics in the elderly. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17(2): 191-205. PubMed

- Jones AG, Hunter JM. Anaesthesia in the elderly: Special considerations. Drugs Aging. 1996;9(5): 319-31. PubMed

- River R, Antognini JF. Perioperative drug therapy in elderly patients. Anesthesiology. 2009; 110(5): 1176-81. PubMed

- Scholz AF, Oldroyd C McCarthy K, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for postoperative delirium among older patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2016; 103(2): e21-8. PubMed

- Ivashkov Y, Vitin A, Rooke GA. General Anesthesia: Intravenous induction agents, inhalational agents, and neuromuscular blockers. In: Barnett SR (Ed), Manual of Geriatric Anesthesia. New York, NY; Springer New York: 2013:93-104.

- Leslie K, Myles PS, Chan MT, t al. Nitrous oxide and long-term morbidity and mortality in the ENIGMA trial. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(2): 387-93. PubMed

- Sprung J, Abcejo ASA, Knopman DS, et al. Anesthesia with and without nitrous oxide and long-term cognitive trajectories in older adults. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(2): 594-604. PubMed

- Eger EI 2nd. Age, minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration, and minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration awake. Anesth Analg. 2001;93(4): 947-53. PubMed

- Schnider TW, Minto CF, Shager SL, et al. The influence of age on propofol pharmacodynamics. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(6): 1502-16. PubMed

- Andres TM, McGrane T, McEvoy MD, et al. Geriatric pharmacology: An update. Anesthesiol Clin. 2019;37(3): 475-92. PubMed

- Reves JG, Barnett SR, McSwain JR, et al. Geriatric Anesthesiology. Cham: Springer; 2018.

- Shafer SL. The pharmacology anesthetic drugs in elderly patients. Anesthesiol Clin North Am. 2000;18(1): 1-29. PubMed

- Das S, Forrest K, Howell S. General anesthesia in elderly patients with cardiovascular disorders: choice of anaesthetic agent. Drug Aging. 2010;27(4): 265-82. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.