Copy link

Perioperative Medication Errors

Last updated: 08/21/2024

Key Points

- Magnitude of Medication Errors: Medication errors represent a significant threat to patient safety, ranking as the third leading cause of death in the United States, with approximately 250,000 deaths annually.1

- Prevalence in the Operating Room (OR): Intraoperative medication errors occur at alarming rates, ranging from more than 1 in 20 medication administrations (4.2%)2 to 1 in 11 medication administrations (9.1%),3 contributing to patient harm and more than $270 per operation in additional cost of care.4

- Challenges in the Perioperative Setting: The operating room environment presents unique challenges with high-acuity patients and a fast-paced care delivery system. These factors lead to a higher number and severity of medication errors compared to non-OR settings.

- Prevention Techniques: Various medication error prevention techniques have been used, including standardization, cultural shifts, and technology interventions such as barcode-assisted labeling tools and clinical decision support (CDS) software.

Introduction

- A medication error is a failure to complete a required action in the medication use process or the use of an incorrect plan or action to achieve a medication-related patient care aim.2

- Medication errors in the OR are common and have a high potential for patient harm. The most common intraoperative medication errors are wrong dose (31%) and wrong medication (24%).5 Between 1 in 20 perioperative medication administrations (4.2%)2 and 1 in 11 medication administrations (9.1%) in the OR involve an error.2 Half of medication errors lead to observed adverse medication events (patient harm), and the remainder has the potential for patient harm.2

- The downstream consequences of intraoperative medication errors are substantial, with an annual additional cost of care of $5.3 billion (more than $270 per operation, on average).4,6

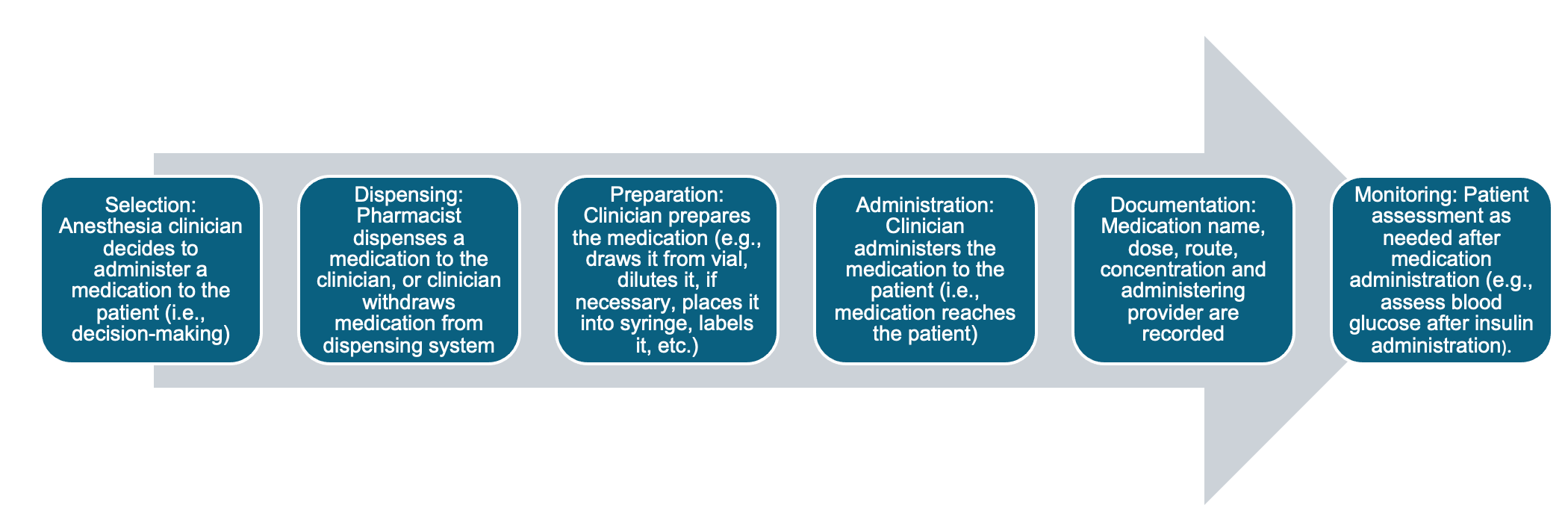

Figure 1. Medication use process. Used with permission from Amici LD et al. Clinical decision support as a prevention tool for medication errors in the operating room: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Anesth Analg.2024.7

Examples of Medication Error Types and Etiologies

Medication Error Types

- Wrong medication (e.g., a medication is administered to a patient who has a known allergy to the medication)

- Wrong dose (e.g., too much local anesthetic is administered to a patient based on their weight)

- Omitted medication (e.g., an antibiotic is not redosed at the appropriate time interval)

- Documentation error (e.g., a medication is administered but not documented)

- Inadvertent bolus (e.g., a medication bolus is administered in the same intravenous line as a vasopressor infusion, inadvertently blousing the vasopressor)

Etiologies

- The OR environment has high-acuity patients and fast-paced care delivery with the real-time completion of the medication use process.

- The OR is the only location in the hospital where a single clinician is responsible for each step in the medication use process without external safety checks or prospective electronic orders.2

- Changes in manufacture labels, packaging, and drug shortages can make look-alike, sound-alike medications a dynamic issue at institutions.

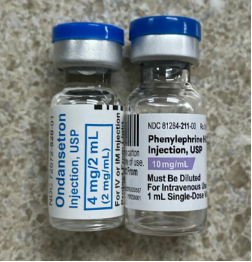

- Look-alike medications (similar in physical appearance, as shown in Figure 2) and sound-alike medications (whose names are identical in spelling or phonetic pronunciation) are frequently involved in medication errors.8

Figure 2. Look-alike medications commonly used in the perioperative setting. Reproduced and modified with permission from the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Myer TA, McAllister RK, 2023;38(2); 47.8

Prevention Techniques

Standardization

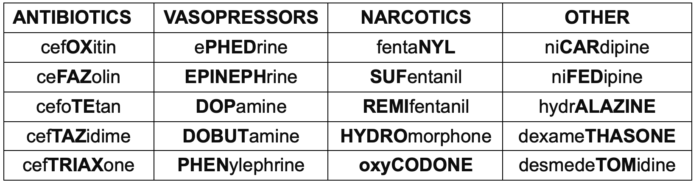

- The tall man lettering system uses uppercase lettering on medication labels to draw attention to the parts of the medication names that are dissimilar,8 which has the following benefits:

- It helps differentiate look-alike and sound-alike medications, reducing the risk of medication errors.

- Enhances readability and recognition (see Table 1)

- Adheres to Food and Drug Administration and The Joint Commission recommendations for using tall man lettering to mitigate the potential for confusion and improve patient outcomes8

Table 1. Tall man lettering of drugs used in the perioperative setting

- Prefilled syringes eliminate the need for manual preparation of medications and streamline the medication use process.

- The benefits include minimizing labeling and dilution errors, improving efficiency and sterility, reducing waste, reducing preparation time, and enhancing patient safety.9

- Disadvantages include increased cost, which can be offset by waste reduction and efficiency gains.3,8

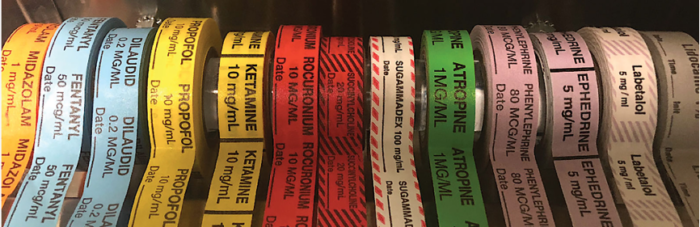

- Color-coding of high-risk medications, as shown in Figure 3, is widely used to classify medications with nine colors, each corresponding to a different medication class. However, professional organizations differ regarding the benefits of color coding for patient safety.10,11

- Advantages include faster medication identification, redundancy cues confirming a medication by name and class/color, and prevention of between-class syringe swaps.10

- Disadvantages: a false sense of security may deter anesthesia clinicians from reading the label, and there is a lack of efficacy for preventing within-class syringe swaps. Colorblind clinicians are at increased risk for misidentifying a label.11

Figure 3. Color-coded labels used in the perioperative setting. Reproduced and modified with permission from the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Janik LS, Vender JS, MD, FCCM;2019; 33 (3); 72.10

- A culture of safety plays a pivotal role in addressing medication errors and includes:

- an environment where individuals feel empowered to report errors without fear of retribution;

- open communication to identify system issues and implement preventive measures;

- a nonpunitive approach focuses on learning from mistakes and improving processes to prevent future errors instead of blaming individuals;

- teams that engage in root cause analysis to understand the underlying factors contributing to errors, whether they stem from communication breakdowns, workflow inefficiencies, or system failures; and

- promoting transparency, accountability, and continuous improvement prioritizes patient safety and reduces the incidence of medication errors.

Technology

- Barcode-assisted medication labeling standardizes medication labels and increases compliance with labeling requirements when prefilled syringes are unavailable.

- During medication preparation, the medication vial barcode is scanned to generate a syringe label. Some labeling technologies also include an auditory readback of the medication name as an additional safety check.12

- Advantages: increased compliance with labeling requirements from regulatory agencies such as The Joint Commission.13

- Disadvantage: has not been shown to prevent medication errors.

- Barcode-assisted medication administration (BCMA) is a technology that allows the medication barcode to be scanned immediately before administration, providing a double check.

- BCMA may also document the medication in the electronic medical record (EMR). While primarily used in inpatient wards, the use of BCMA intraoperatively has increased.14

- Smart infusion pumps are mechanical devices that infuse intravenous medications and may incorporate alerting algorithms to help reduce medication errors.

- Advantages: Features such as minimum and maximum dose alerts, concentration alerts, and drug libraries can help reduce medication errors such as incorrect pump programming and keystroke errors.

- Disadvantages: These features must be appropriately used by clinicians (and not bypassed) to prevent medication errors. Alarm fatigue and the labor-intensive process of building/maintaining custom drug libraries differ between institutions.15

- Clinical decision support software (CDS) involves comprehensive algorithms that provide evidence-based information to clinicians at the point of care to enhance decision-making and prevent errors.7

- CDS can be integrated into the EMR and is typically used with BCMA to improve safety by targeting each step of the medication use process. The anesthesia clinician confirms the medication dose and documents it automatically in the EMR.

- Emerging data show that CDS can potentially prevent 95% of intraoperative medication errors.7 Perioperative CDS technologies have been shown to reduce costs and prevent medication errors, improve quality of care and workflow efficiency, and reduce costs.4,7

Professional Recommendations

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice (ISMP) 2022 Guidelines: Link

- The best medication labeling and storage practices include covering essential elements such as medication standardization and utilization of medication delivery devices.

- Challenge conventional practices that may compromise the effectiveness of safety technologies like smart infusion pumps.

- Recommend widespread adoption of barcode scanning technology and CDS to facilitate real-time medication checks and automated documentation, thereby enhancing medication safety in perioperative and procedural settings.

- Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) 2022 Recommendations: Link

- Use prefilled syringes and pre-prepared infusions to reduce errors and waste

- Implement electronic medication scanning at the point of care with CDS.

- Use standardized medication vials and color-coded labels to enhance identification

- Adopt standard medication concentrations across different care areas

- Develop online resources tailored to anesthesia professionals working in settings with limited resources, such as surgery centers and community hospitals, to promote best medication safety practices

References

- Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016; 353: i2139. PubMed

- Nanji KC, Patel A, Shaikh S, et al. Evaluation of perioperative medication errors and adverse drug events. Anesthesiology. 2016;124(1):25-34. PubMed

- Merry AF, Webster CS, Hannam J, et al. Multimodal system designed to reduce errors in recording and administration of drugs in anaesthesia: prospective randomised clinical evaluation. BMJ. 2011;343: d5543. Link

- Langlieb ME, Sharma P, Hocevar M, et al. The additional cost of perioperative medication errors. J Patient Saf. 2023;19(6):375-8. Link

- Bowdle T. Drug administration errors from the ASA Closed Claims Project. Link

- Nanji KC, Shaikh SD, Jaffari A, et al. A Monte Carlo simulation to estimate the additional cost associated with adverse medication events leading to intraoperative hypotension and/or hypertension in the United States. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(8): e758-e764. PubMed

- Amici LD, Van Pelt M, Mylott L, et al. Clinical decision support as a prevention tool for medication errors in the operating room: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Anesth Analg. Link

- Meyer TA, McAllister RK. Medication errors related to look-alike, sound-alike drugs—How big is the problem and what progress is being made? Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Accessed April 17, 2024. Link

- Malik P, Rangel M, VonBriesen T. Why the utilization of ready-to-administer syringes during high-stress situations is more important than ever. J Infus Nurs Off Publ Infus Nurses Soc. 2022;45(1):27-36 Link

- Janik LS, Vender JS. Pro/Con Debate: Color-Coded Medication Labels - PRO: Color-Coded Medication Labels Improve Patient Safety. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Accessed April 20, 2024. Link

- Grissinger M, Litman RS. Pro/Con Debate: Color-Coded Medication Labels - CON: Anesthesia Drugs Should NOT Be Color-Coded. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Accessed April 20, 2024. Link

- Jelacic S, Bowdle A, Nair BG, et al. A system for anesthesia drug administration using barcode technology: The Codonics Safe Label System and Smart Anesthesia ManagerTM. Anesth Analg. 2015;121(2):410-21. PubMed

- National Patient Safety Goals Effective January 2024 for the Ambulatory Health Care Program. Link

- Poon EG, Keohane CA, Yoon CS, et al. Effect of bar-code technology on the safety of medication administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(18):1698-1707. PubMed

- Vanderveen T, O'Neill S, Beard JW. How can we tell how “smart” our infusion pumps are? Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Published February 2020. Accessed April 20, 2024. Link

- Nanji KC, Garabedian PM, Langlieb ME, et al. Usability of a perioperative medication-related clinical decision support software application: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2022;29(8):1416-24. PubMed

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.