Copy link

Pediatric Upper Respiratory Infection and Anesthesia

Last updated: 04/06/2023

Key Points

- Upper respiratory infections (URIs) are common in children presenting for general anesthesia and increase the risk of perioperative respiratory adverse events (PRAE).

- Several independent risk factors have been identified and should be taken into consideration when deciding to cancel or postpone a child’s anesthetic.

- Certain anesthetic practices may mitigate the risk of PRAE, including an intravenous induction and the use of a supraglottic airway (SGA) or mask airway.

- Children with active or recent URIs undergoing general anesthesia are not at a higher risk of long-term sequelae.1

Prevalence and Risk of URI

- PRAE occur in 15-50% of all children undergoing general anesthesia.2

- Between 25-45% of children presenting for surgery have an active or recent URI, as defined by a parent’s report of a “cold,” which includes rhinorrhea, sneezing, cough, malaise, and/or fever.3

- Children generally have many URIs per year, leaving a narrow window of opportunity to schedule elective surgeries at a time when the child does not have an active or recent (less than 4 weeks prior) URI.

- Various studies cite differing prevalence of PRAE in the setting of URIs, such as breath holding,1,4 arterial oxygen desaturation (<90%),1,4 laryngospasm, and bronchospasm.1,2

Risk Factors

Patient Factors

- American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status greater than 1, history of prematurity (less than 37 weeks), history of reactive airway disease, parental smoking, nocturnal snoring, history of eczema1,2,4

Clinical Factors

- Parent’s belief that the child has a cold: copious secretions, nasal congestion, sputum production with coughing, dry nocturnal cough, fever4

URI 4 weeks prior to surgery1,2,4

Surgical Factors

- Airway surgery: tonsillectomy, direct laryngoscopy, and bronchoscopy1

Airway Reactivity

- Viral infection of mucosal membranes causes airway inflammation and increased secretions with increased airway susceptibility to bronchial hyperreactivity.3

- URIs cause morphological damage to respiratory endothelium which sensitize the airway to anesthetic gases. This results in activation of smooth muscle contraction in the airway.5

- Neuraminidase is produced by some viruses which inhibits muscarinic type 2 receptors which increase acetylcholine, leading to smooth muscle contraction.3

- Tachykinin and neuropeptides are released by some viruses and can lead to bronchospasm.3

Anesthetic Considerations

Airway Management

- Endotracheal intubation may increase the likelihood of PRAE in children with URIs compared to face masks or SGA.1,4

- A systematic review found that using an SGA did not decrease the incidence of PRAE compared to endotracheal tubes.6

- SGA use significantly reduces the risk of perioperative coughing compared to endotracheal tubes.6

- Airway management should be done by an experienced pediatric anesthesia provider.2

Anesthetic Agents

- Intravenous induction with propofol leads to significantly less adverse airway events than an inhalational induction with sevoflurane.7

- Maintenance with sevoflurane is associated with a lower incidence of PRAE compared to isoflurane or halothane.1

- Failure to reverse neuromuscular blockade is associated with an increased likelihood of adverse airway event.4

Bronchodilators

- Preoperative administration of albuterol has been shown to reduce PRAE.8

Lidocaine

- Intravenous lidocaine may reduce airway reactivity for a short period of time.9

- Topical lidocaine gel may be applied to the SGA to reduce the incidence of postoperative coughing.10

- Spraying aerosolized lidocaine on the vocal cords may increase the risk of laryngospasm and bronchospasm; however, studies differ on this effect.2

Timing of Surgery

- Given the prolonged period of airway hyperreactivity, there are some recommendations to delay surgery for 4-6 weeks in the setting of a URI.1-3

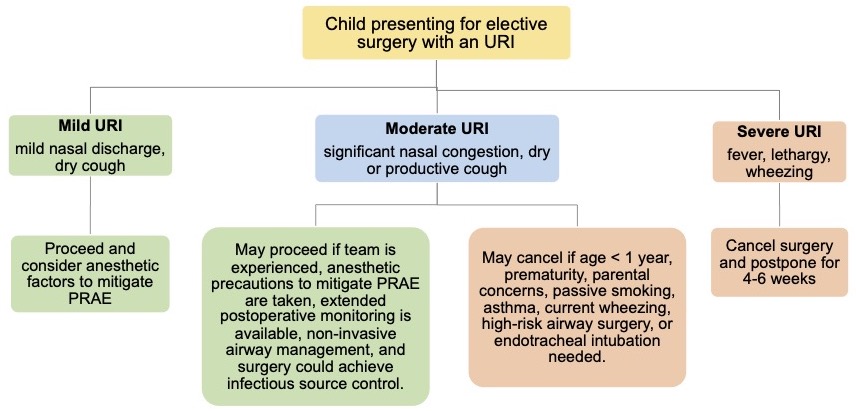

- However, an algorithm such as the one below considers the risks and benefits of cancellation on an individualized basis3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Algorithm to guide the perioperative management of children presenting for elective surgery with an URI. Adapted from Regli A, et al. An update on the perioperative management of children with upper respiratory tract infections. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30(3):362-7.3

References

- Tait AR, Malviya S, Voepel-Lewis T, et al. Risk factors for perioperative adverse respiratory events in children with upper respiratory tract infections. Anesthesiology. 2001; 95:299–306. PubMed

- von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Boda K, Chambers NA, et al. Risk assessment for respiratory complications in paediatric anaesthesia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2010; 376:773–83. PubMed

- Regli A, Becke K, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. An update on the perioperative management of children with upper respiratory tract infections. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017;30(3):362-7. PubMed

- Parnis SJ, Barker DS, Van Der Walt JH. Clinical predictors of anaesthetic complications in children with respiratory tract infections. Paediatr Anaesth. 2001;11(1):29-40. PubMed

- Little JW, Hall WJ, Douglas RG Jr, et al. Airway hyperreactivity and peripheral airway dysfunction in influenza A infection. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118(2):295-303. PubMed

- de Carvalho ALR, Vital RB, de Lira CCS, et al. Laryngeal mask airway versus other airway devices for anesthesia in children with an upper respiratory tract infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis of respiratory complications. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(4):941-50. PubMed

- Ramgolam A, Hall GL, Zhang G, et al. Inhalational versus IV induction of anesthesia in children with a high risk of perioperative respiratory adverse events. Anesthesiology. 2018;128(6):1065-74. PubMed

- von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Habre W, Erb TO, et al. Salbutamol premedication in children with a recent respiratory tract infection. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19(11):1064-9. PubMed

- Erb TO, von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Keller K, et al. The effect of intravenous lidocaine on laryngeal and respiratory reflex responses in anaesthetised children. Anaesthesia. 2013;68(1):13-20. PubMed

- Schebesta K, Güloglu E, Chiari A, et al. Topical lidocaine reduces the risk of perioperative airway complications in children with upper respiratory tract infections. Can J Anaesth. 2010;57(8):745-50. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.