Copy link

Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury

Last updated: 02/19/2025

Key Points

- Pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI) can occur via accidental or nonaccidental trauma (NAT).

- Specific evidence-based guidelines exist for perioperative TBI in the pediatric population.

- The goals of intraoperative anesthetic management are to attenuate primary injury, cerebral edema, and elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) and to prevent secondary injury from hypoxemia and hypotension.

Definition and Classification

- TBI is the leading cause of disability and death in children, with specific and distinctive characteristics attributable to age-related differences in anatomy, physiology, and types of injury.1-3

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 475,000 people in the United States between 0 and 14 years sustain a TBI annually, with the majority (90%) returning home with mild injuries. However, 37,000 are hospitalized, and 2,685 die due to injuries.

- Children aged 0-1 years had the highest rate of emergency evaluation (1,035 per 100,000), and 80 per 100,000 were hospitalized. Only 5 per 100,000 died from their injuries, with a higher rate observed in 5–14 year olds. This may be reflective of NAT injuries as approximately 30 of every 100,000 infants younger than 1 year old were hospitalized with TBI related to NAT. Adolescents are the most common age group to be hospitalized (129 per 100,000). Falls are the leading cause of TBI in all age groups. Motor vehicle accidents, other transportation-related accidents, and NAT are other leading causes.

- Regardless of injury type, TBI consists of a two-hit phenomenon, with the first hit being direct neuronal injury and the subsequent hit due to additional hypoxemia and hypotension which exacerbate cellular and physiologic changes.4

- TBI can be classified based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (see Traumatic Brain Injury OA summary for more details).

- The GCS is commonly used to rapidly evaluate trauma patients. See Initial Evaluation of Trauma Patients OA summary for more details). Table 1 lists a modified GCS scoring system for pediatric use.

Table 1. Modified pediatric Glasgow coma scale. Adapted from James HE, Trauner DA. The Glasgow coma scale. In: James HE, Anas NG, Perkin RM, eds. Brain insults in infants and children. Orlando: Grune & Stratton; 1985: 179- 182.5

Elevated ICP Definition

- Intracranial pressure (ICP) is the pressure within the cranial vault. The pressure, measured in mmHg, usually is less than 20 mm Hg. However, in the setting of TBI, cytotoxic and vasogenic swelling can occur.

- Because the cranium has a fixed bony container (e.g., the skull), ICP can increase as edema or bleeding accumulates. As pressure exceeds the normal ICP, cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) and venous blood flow move down the spinal column to allow for arterial blood flow. When ICP exceeds mean arterial pressure (MAP), tissue perfusion is compromised. Decreasing elevated ICP and increasing MAP to maintain cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is the cornerstone of management to prevent a second hit to neuronal health.

- See Elevated Intracranial Pressures OA summary for more details.

Management of Pediatric Severe TBI

- A summary of the Guidelines for the Management of Pediatric Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Third Edition: Update of the Brain Trauma Foundation Guidelines is listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of recommendations per the Guidelines for Management of Pediatric Severe Traumatic Brain Injury.6,7 Abbreviations: ICP, intracranial pressure; ICH, intracranial hypertension; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; HTS, hypertonic saline

Anesthetic Considerations

Goals

Maintaining adequate CPP by maintaining or elevating MAPs and lowering ICPs.

Additional insults (listed below) should be avoided.

- Seizures

- Coagulopathy

- Hypoglycemia

- Hypoxemia

- Hypotension

- Extremes of ventilation/carbon dioxide

Airway Management

Early intubation is recommended in patients with TBI. Criteria include:

- GCS less than 8

- GCS falling by more than 3 points between serial clinical exams

- Hypoxia despite supplemental oxygen

- Apnea

- Hypercarbia

Monitoring

- Standard American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) monitors should be used.

- An arterial line should be placed as soon as possible to monitor CPP closely.

- Central venous access may be required to augment MAPs to support CPP.

Induction of Anesthesia

- Assume full stomach prior to induction, maintain cervical stabilization, and maintain CPP while avoiding further increases in ICP

- Masking may be difficult in the setting of associated facial polytrauma.

- Benzodiazepines should be avoided as they may interfere with postoperative exams.

- Succinylcholine can briefly increase ICP but can be used without other absolute contraindications.

- Awake intubations are unlikely to be tolerated in patients with worsening mental status due to TBI.

Maintenance of Anesthesia

- Sub-mean alveolar concentrations of inhaled anesthetic can be coupled with short-acting opiates to facilitate postoperative neurologic exams.

- Total intravenous anesthesia can be performed so long as CPP is maintained, and a neurologic exam can be performed quickly after the conclusion of the procedure.

Seizure Prophylaxis

- Protocolized use of antiepileptics often includes levetiracetam or fosphenytoin.

- While the choice of medication is usually hospital protocol-specific, these should be continued in the postoperative period.

Fluids and Electrolytes

- Mannitol and hypertonic saline may be used to acutely lower ICP. Repeated dosing of mannitol is not recommended as it can result in intravascular volume contraction.

- The blood-brain barrier is altered following TBI, and colloids can extravasate, worsening cerebral edema. Colloids, including albumin, should be avoided.

- The use of warmed nonglucose-containing fluids is recommended to maintain total body fluid status.

- Blood product transfusions should be administered for clinical status changes due to patient-level factors, including ongoing bleeding. Maintain Hgb more than 7 g/mL.

Cerebral Perfusion Pressure Goals

- CPP=MAP-ICP

- Goal CPP more than 50 mmHg in age 6-17 years

- Goal CPP more than 40 mmHg in age 0-5 years

- In lieu of ICP monitoring, goal systolic blood pressure more than 75th percentile for age

Table 3. Estimated cerebral perfusion pressure and corresponding mean arterial pressures by age

Monitoring for Increased ICP

- Patients with a GCS of less than 8 should have invasive ICP monitoring.

- EVDs have the advantage of monitoring ICP and the ability to drain CSF directly.

- Non-EVD monitors can monitor ICP, and some can monitor tissue oxygenation.

Patient Positioning

- Patients should be positioned at 30 degrees head up to optimize venous draining while limiting gravitational effects on MAP.

- The neck should remain neutral, with the cervical spine collar snug enough to maintain support but loose enough not to impede drainage.

Intraoperative Interventions for Elevated ICP

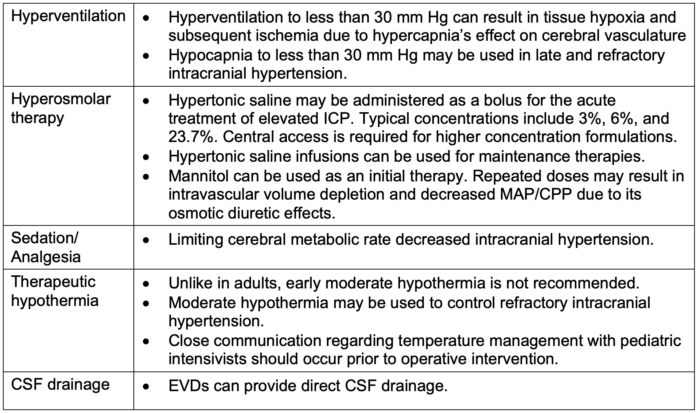

- Recommendations for the intraoperative management of severe TBI are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Recommendations for the intraoperative management of severe TBI

Definitive Therapy: Decompressive Craniectomy

- When other interventions have failed to adequately reduce intracranial pressure, either a bifrontal or a large unilateral frontotemporoparietal decompressive craniectomy may be used.

- Without the fixed volume compartment (skull), the brain may expand caudally, and initial medical therapies may be weaned to normal parameters.

- Mortality outcomes can be as high as 30%, but early decompression may afford improved survival and functionality.

References

- TBI data in the United States. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. Link

- Araki T, Yokota H, Morita A. Pediatric traumatic brain injury: Characteristic features, diagnosis, and management. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2017;57(2):82-93. PubMed

- Maas AIR, Menon DK, Manley GT, et al. Traumatic brain injury: progress and challenges in prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(11): 1004-60. PubMed

- Traumatic brain injury. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. 2024. Link

- James HE, Trauner DA. The Glasgow coma scale. In: James HE, Anas NG, Perkin RM, eds. Brain insults in infants and children. Orlando: Grune & Stratton; 1985: 179- 182.

- Kochanek PM, Tasker RC, Carney N, et al. Guidelines for the management of pediatric severe traumatic brain injury, third edition: Update of the Brain Trauma Foundation Guidelines, Executive Summary. Neurosurgery. 2019;84(6):1169-78. PubMed

- Kochanek P, Tasker RC, Bell MJ, et al. Management of pediatric severe traumatic brain injury: 2019 Consensus and guidelines-based algorithm for first and second tier therapies. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019; 20(3): 269-79. PubMed

Other References

- Hardcastle N, Benzon HA, Vavilala MS. Update on the 2012 guidelines for the management of pediatric traumatic brain injury - information for the anesthesiologist. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014;24(7):703-10. PubMed

- Ocasio-Rodríguez CM, Puig-Ramos A, García-De Jesús R. Long-term pediatric outcomes of decompressive craniectomy after severe traumatic brain injury. P R Health Sci J. 2023;42(2):152-7. PubMed

- Lee, JK, Brady K, Deutsch N. The anesthesiologist’s role in treating abusive head trauma. Anesth Analg. 2016; 122(6): 1971-82. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.