Copy link

Pediatric Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy

Last updated: 03/08/2023

Key Points

- Two common indications for tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy are obstructive sleep-disordered breathing (OSDB) and recurrent throat infections.

- A multimodal analgesic approach should be used to minimize opioid use, especially in patients with OSDB, due to the higher risk of respiratory depression.

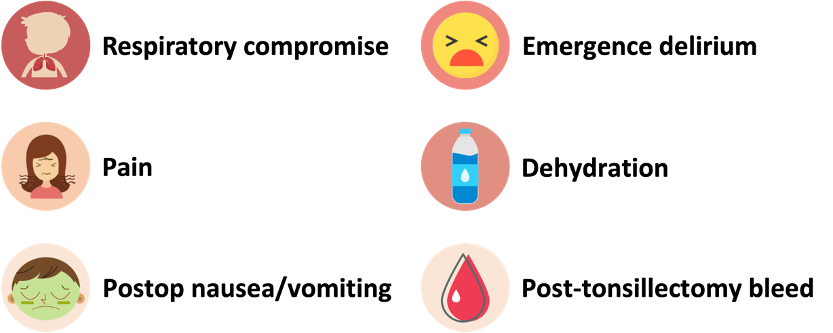

- Common postoperative complications include respiratory compromise, pain, postoperative nausea and vomiting, emergence delirium, dehydration, and posttonsillectomy hemorrhage.

Indications

- Tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy is the second most common ambulatory surgery performed on children in the United States after myringotomy and tube placement.1

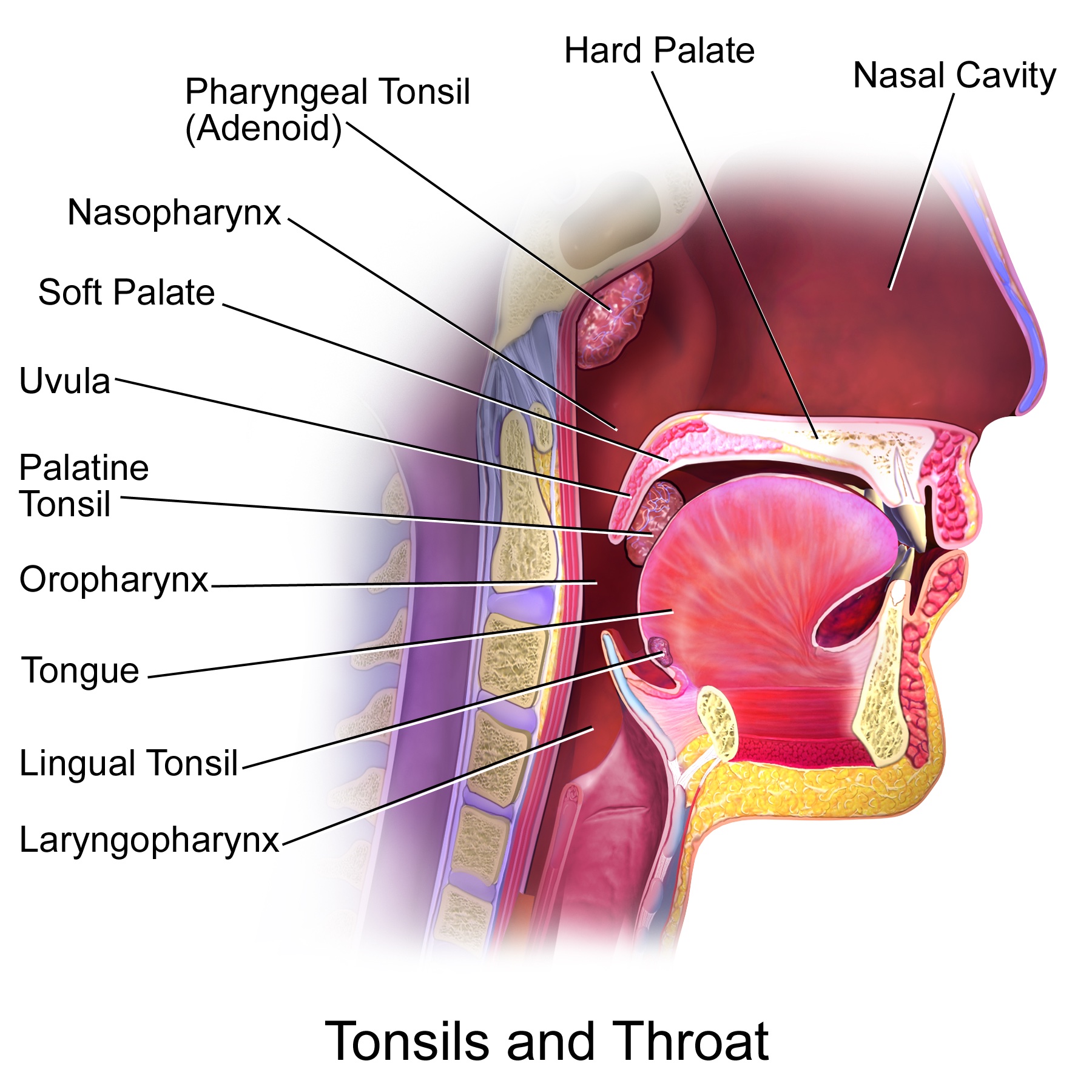

- The tonsils are a set of lymphoid organs that play an important role in the immune system. There are four different types of tonsils that make up the Waldeyer’s ring (Figure 1).

- Palatine tonsils: one on either side of the oropharynx between the palatoglossal and palatopharyngeal arches

- Adenoids or pharyngeal tonsils: located in the roof of the pharynx

- Tubal tonsils: one on either side located posterior to the opening of the eustachian tube on the lateral wall of the nasopharynx.

- Lingual tonsils: located behind the tongue

Figure 1. Tonsils and throat anatomy. Source: Wikimedia. BruceBlaus. Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014. CC BY 3.0 Link

- Two common indications for tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy are obstructive sleep-disordered breathing (OSDB) and recurrent throat infections.

- OSDB: A spectrum of disorders ranging from snoring to hypoventilation and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). About 40% of children with OSBD exhibit behavioral problems (enuresis, hyperactivity, aggression, anxiety, depression, and somatization). OSA can be associated with poor school performance.

- Recurrent throat infections (tonsillitis, pharyngitis, peritonsillar abscess): Sore throat caused by viral or bacterial infections of the pharynx, palatine tonsils or both, which may or may not be cultured positive for group A streptococcus. Tonsillectomy is recommended for recurrent throat infections with a frequency of

- at least seven episodes in the last year;

- at least five episodes per year for two years; or

- at least three episodes per year for three years.1

Preoperative Evaluation

- History: Upper respiratory infections (URI), signs or symptoms of OSA, bleeding disorders

Children can have frequent URIs, and airway reactivity can persist for 2-4 weeks after the resolution of symptoms. - The STBUR questionnaire (Snoring, Trouble Breathing and Un-Refreshed) is a practical tool to identify children with OSDB who may be at an elevated risk of perioperative respiratory adverse events:2

“While sleeping, does your child…

1) … snore more than half the time?

2) … snore loudly?

3) … have trouble breathing or struggle to breathe?

4) Have you ever seen your child stop breathing during the night?

5) Does your child wake up feeling unrefreshed in the morning?”

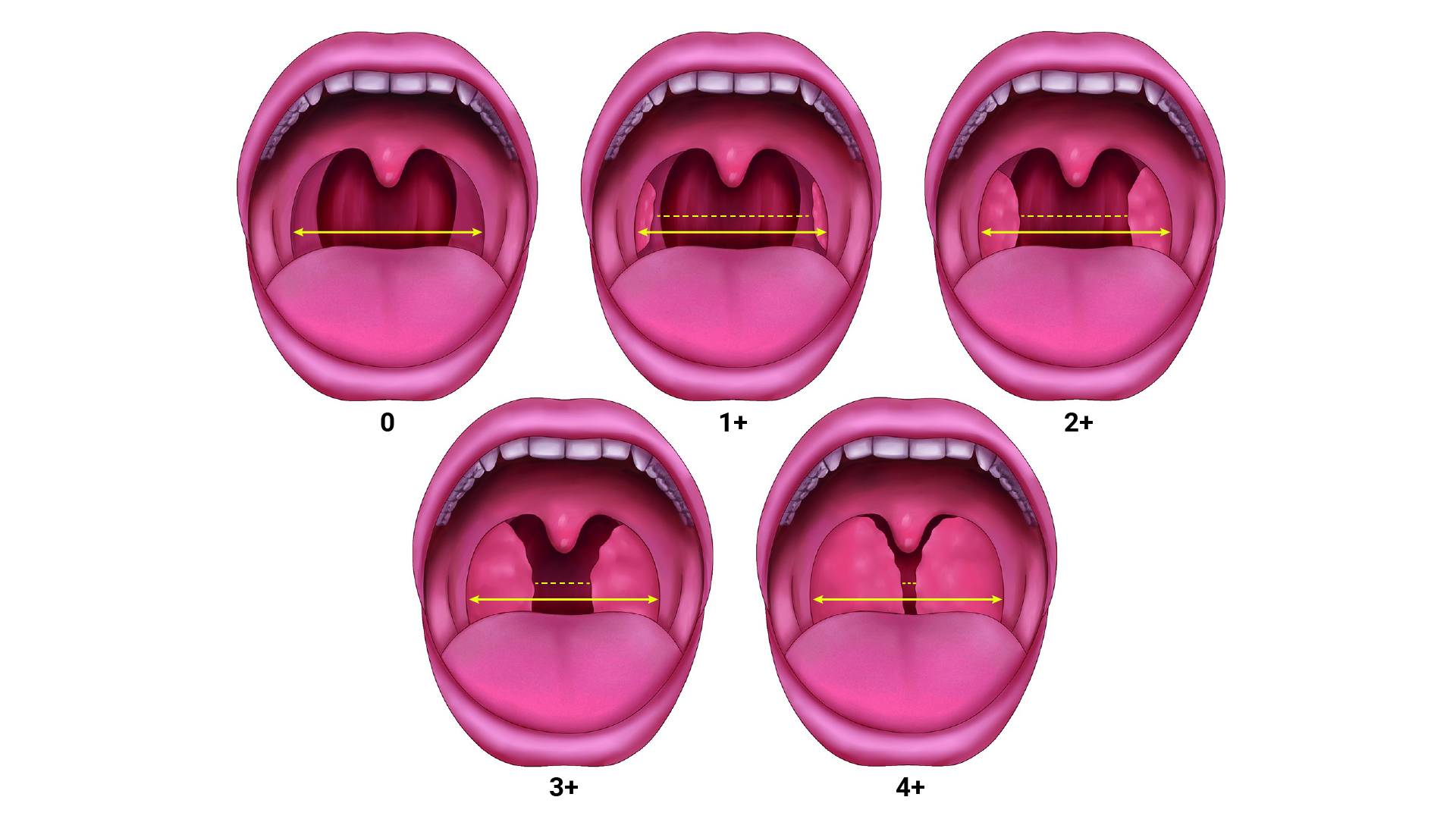

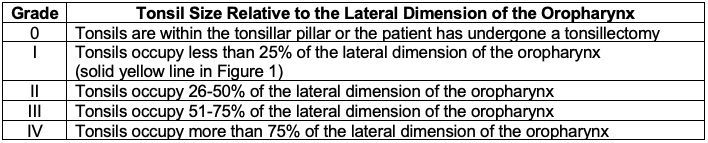

* Presence of any three positive STBUR symptoms increased the risk of a perioperative airway event by 3-fold, and if all five STBUR symptoms, the risk increases by 10-fold. - Physical examination: Focused airway exam, including tonsil size (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2. Grading of tonsil size relative to the lateral dimension of the oropharynx. Adapted from Drutz JE. The pediatric physical examination: HEENT. In: Duryea TK, ed. UpToDate; 2022. Accessed Dec 23rd, 2022.

Table 1. Grading of tonsil size.

- Indications for polysomnography in children with OSDB include

- less than two years of age;

- obesity;

- Down syndrome;

- craniofacial abnormalities;

- neuromuscular disorders;

- sickle cell disease; and

- mucopolysaccharidoses.

- Hematologic evaluation is not necessary unless family or patient history is concerning for a bleeding disorder.

Anesthetic Considerations

- The 2018 guidelines developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAOHNS) provide evidence-based recommendations for the pre-, intra- and postoperative care to optimize safety.1

- Risks of general anesthesia after a current or recent URI include laryngospasm, bronchospasm, stridor, cough, hypoxia, and unanticipated admission or need for intensive care. Patient-specific risk factors include a history of prematurity, younger age (1 year), reactive airway disease, and exposure to smoke. Surgeries requiring endotracheal intubation and those involving the airway are associated with a higher risk.

- Preoperative albuterol has been shown to reduce the occurrence of respiratory adverse events in children undergoing tonsillectomies.3

- The severity of OSDB remains a major risk factor for the development of perioperative respiratory events (postoperative pulmonary edema, pneumonia, airway obstruction). Obesity appears to be the most significant factor associated with OSA in children.4 Patients with OSDB tend to have increased analgesic sensitivity to opiates.5

- The inspired oxygen concentration (FIO2) should be maintained less than 30% to prevent airway fires.

- A cuffed oral Ring Adair, and Elwyn (RAE) tube is typically used for endotracheal intubation to allow the use of a Davis Crowe mouth gag or similar device for surgical suspension.

- In patients with Down syndrome or those with atlantoaxial instability (e.g., mucopolysaccharidoses, achondroplasia, etc.), neck extension should be minimized.

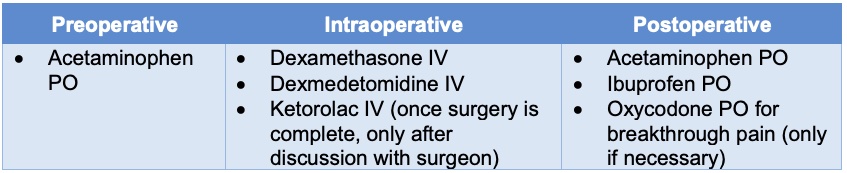

- A multimodal analgesic approach should be used to minimize opioid use, especially in patients with OSDB, due to the higher risk of respiratory depression (Table 2).

Table 2. Sample opioid-sparing multimodal analgesic approach for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Adapted from Franz et al. The development of an opioid sparing anesthesia protocol for pediatric ambulatory tonsillectomy and adenotonsillectomy surgery: A quality improvement project. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019;29(7):682-9.6

- A single intraoperative dose of intravenous dexamethasone is strongly recommended for analgesia and the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV).1 Higher doses of dexamethasone can also decrease airway swelling.

- Dexmedetomidine is a selective alpha adrenoreceptor agonist with both analgesic and sedative properties. Intraoperative dexmedetomidine (0.5-1 mcg/kg IV) is associated with an overall perioperative opioid-sparing effect without respiratory depressant effects.7 Higher doses (> 1 mcg/kg) can cause sedation and prolonged PACU stay. The incidence and duration of emergence agitation was also lower when an intraoperative dexmedetomidine dose was given.8

- Intraoperative ketorolac is not widely administered since nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs inhibit platelet aggregation and prolong bleeding time, which could cause increased posttonsillar bleeding. Despite numerous reviews of randomized controlled trials, there remains insufficient evidence to exclude an increased risk of bleeding with ketorolac administration.9

- The use of at least two antiemetic agents is recommended due to the high risk of PONV.

- The high risk of laryngospasm and increased airway reactivity make emergence from anesthesia after tonsillectomy challenging. The oropharynx should be carefully suctioned prior to extubation for removal of blood and secretions. The surgeon or anesthesiologist may use an orogastric tube to empty the stomach.

- There is varying practice around awake vs. deep extubation. Awake extubation assures protection from airway obstruction and aspiration, but may be associated with coughing and bucking, with a potentially higher risk of postoperative bleeding, wound dehiscence, and desaturation. Deep extubation removes the coughing stimulus, but leaves the patient with an unprotected airway, potentially increasing the risk of airway obstruction and aspiration.10 Careful patient selection is key to a successful extubation strategy.

Postoperative Complications

- Although a common procedure, tonsillectomy with or without adenoidectomy is not without significant risk ranging from minimal to life-threatening complications.

- Common postoperative complications include:

- The surgical approach can affect the level of postoperative pain and post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage. Tonsillotomies tend to have the lowest rate of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage and less postoperative pain (Table 3).7

Table 3. Surgical approaches to tonsillectomy

- Commonly used indications for overnight admission for monitoring include1,12

- patients younger than three years;

- severe OSA (apnea-hypopnea index ≥10 obstructive events/hour, oxygen saturation nadir <80%, or both);

- obesity: body mass index greater than 95th percentile;

- Trisomy 21;

- craniofacial anomalies;

- Sickle cell disease;

- neuromuscular disorders;

- mucopolysaccharidoses; and

- bleeding diathesis.

References

- Mitchell RB, Archer SM, Ishman SL, et al. Clinical practice guideline: Tonsillectomy in children (Update)—Executive summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160(2):187-205. PubMed

- Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Christensen R, O'Brien LM. The STBUR questionnaire for predicting perioperative respiratory adverse events in children at risk for sleep-disordered breathing. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(6):510-6. PubMed

- von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Sommerfield D, Slevin L, Drake-Brockman TFE, Zhang G, Hall GL. Effect of albuterol premedication vs placebo on the occurrence of respiratory adverse events in children undergoing tonsillectomies: The REACT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(6):527-33. PubMed

- McGuire SR, Doyle NM. Update on the safety of anesthesia in young children presenting for adenotonsillectomy. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;7(3):179-85. PubMed

- Brown KA, Laferriere, A, Lakheeram I, et al. Recurrent Hypoxemia in Children Is Associated with Increased Analgesic Sensitivity to Opiates. Anesthesiology. 2006; 105(4): 665-9. PubMed

- Franz AM, Dahl JP, Huang H, et al. The development of an opioid sparing anesthesia protocol for pediatric ambulatory tonsillectomy and adenotonsillectomy surgery-A quality improvement project. Paediatr Anaesth. 2019;29(7):682-9. PubMed

- Olutoye OA, Glover CD, Diefenderfer JW, et al. The effect of intraoperative dexmedetomidine on postoperative analgesia and sedation in pediatric patients undergoing tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(2):490-5. PubMed

- Di M, Han Y, Yang Z, et al. Tracheal extubation in deeply anesthetized pediatric patients after tonsillectomy: a comparison of high-concentration sevoflurane alone and low-concentration sevoflurane in combination with dexmedetomidine pre-medication. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17(1):28. PubMed

- Lewis SR, Nicholson A, Cardwell ME, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and perioperative bleeding in paediatric tonsillectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(7):CD003591. PubMed

- Baijal RG, Bidani SA, Minard CG, et al. Perioperative respiratory complications following awake and deep extubation in children undergoing adenotonsillectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(4):392-9. PubMed

- Francis DO, Fonnesbeck C, Sathe N, et al. Postoperative bleeding and associated utilization following tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(3):442-55. PubMed

- Nardone HC, McKee-Col KM, Friedman NR. Current pediatric tertiary care admission practices following adenotonsillectomy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142(5): 452-6. PubMed

Other References

- Sinskey JL. Tonsillectomy with or without Adenoidectomy. OpenAnesthesia. Published August 1, 2020. Accessed March 8, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.