Copy link

Pediatric Consent and Assent

Last updated: 02/20/2025

Key Points

- Clinicians must obtain legal consent and try to gain assent from pediatric patients when appropriate.

- Clinicians should consider the rule of 7s and the basic requirements for a minor to possess the capacity to assent to medical decisions.

- Clinicians should refer to state-specific guidelines for medical decision-making processes.

Consent Versus Assent

- Obtaining consent and assent is crucial in medical and surgical procedures, but it can be complicated when a patient’s capacity is unclear.

- Consent is the legal permission required for treatment, while assent is the patient’s understanding and agreement to the process. Adults may be legally capable of consenting but might lack the ability to comprehend treatment implications due to conditions like dementia.

- Pediatric cases pose additional challenges. Children may come from unstable home environments or have parents who are unable to make informed decisions due to incarceration or incapacity.

- Even in supportive family situations, a child might be anxious or refuse treatment, raising questions about their involvement in medical decisions.

Medical Decision-Making

- There are four principles necessary for a person to be able to make their own medical decisions: understanding, reasoning, appreciation, and expressing a choice.2

- Understanding involves having the intellectual capacity to comprehend a proposed plan and recognize that a choice must be made. For adult patients, this requires fluency in the language. Minors must be old enough to listen, process information, form complete thoughts, and communicate effectively. Basic language skills usually develop in the first few years of life. To truly understand, one also needs to pay direct attention to information and develop the ability to form and recall memories. These memory skills typically develop between the ages of 7 and 12 years.2

- Reasoning refers to the ability to consider different options and anticipate possible outcomes. For instance, if a patient has a high familial risk of colon cancer and needs routine screening, they must understand that choosing not to undergo the procedure could lead to a late diagnosis and treatment of a potentially lethal and also treatable condition. Generally, children begin to reason around the ages of 6 to 8 years. However, more advanced reasoning skills evolve as children gain experience and learn to weigh risks and benefits more effectively.

- Appreciation, or understanding the implications of a situation, is more challenging to define within a specific age range. A person’s ability to appreciate a situation is heavily influenced by their previous experiences. For example, children as young as 3 or 4 can appreciate simple consequences, such as feeling pain after touching a hot stove. However, understanding more complex, abstract situations requires advanced thinking and the ability to foresee the potential consequences of decisions.

- Expressing a choice requires the ability to communicate a preference, usually through verbal language. This ability develops in early childhood but can vary significantly from person to person and may be influenced by underlying medical conditions.

- There are various approaches to determining medical surrogacy, including the best interest standard, the harm principle, constrained parental autonomy, and shared family-centered decision-making.

- Typically, legal guardians or parents serve as the primary decision-makers, as they are expected to understand the child best and act in their best interests. This aligns with the best interest standard.1

- The harm principle offers more flexibility in deciding which options are acceptable. Clinicians establish a harm threshold, below which parental decisions are generally tolerated. As long as these limits are not exceeded, a single treatment approach does not have to be strictly applied, which can be too restrictive for a particular child.1

- For example, a parent may insist on being present during induction, believing it will reduce the child’s anxiety. While studies have indicated this may not be effective, it could be permitted under this philosophy as long as it does not cause harm. However, if a parent’s presence during induction interferes with a clinician’s intervention — such as during a laryngospasm — the medical team has the authority to remove the parent from the operating room to ensure the child’s safety and appropriate care.

Rule of 7s

- The “age of majority” refers to the legal threshold at which a person is recognized as an adult and can consent to medical interventions. This age varies by jurisdiction, but it is set at 18 years in most states in the United States.

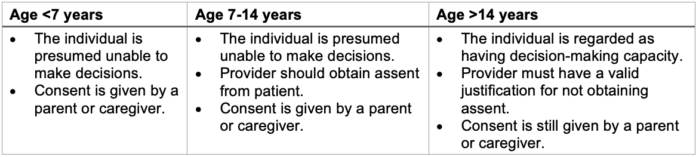

- In the 1987 case Cardwell v. Bechtol, the Tennessee Supreme Court applied the “rule of sevens” to affirm the decision-making capacity of a 17-year-old girl undergoing spinal manipulation.1 According to this guideline, children younger than 7 years are considered to lack decision-making capacity. For children aged 7 to 14 years, there is a presumption of a lack of capacity, but healthcare providers are encouraged to seek their assent. Adolescents older than 14 years are treated as having decision-making capacity, even if a legal guardian’s consent is needed.2

Table 1. Rule of 7s: considerations for determining the involvement of a minor in decision-making.2

Pediatric Assent

- Pediatric providers should be skilled in communicating with pediatric patients using language appropriate for the individual’s developmental stage. Diagrams and videos can help illustrate what the child can expect at each treatment step.

- Cautiously explaining potential feelings and emotions—both positive and negative—is crucial for maintaining trust. A relationship built on trust and respect fosters developmental growth and autonomy in children from a young age.

- There are varying perspectives on what pediatric assent entails.

- A stricter interpretation suggests that a patient must be able to understand and make an informed decision on par with an adult. This view inherently excludes younger children from being able to provide assent.1

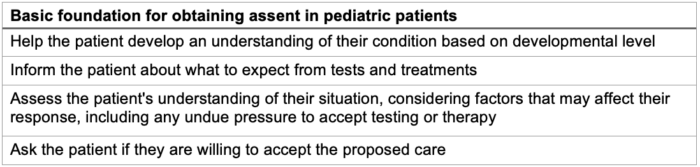

- A more liberal approach emphasizes assessing a minor’s developmental stage and adjusting expectations accordingly. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, assent should include the minimum elements listed in Table 2.1

Table 2. Practical aspects of obtaining assent in pediatric patients. Adapted from Katz AL, et al. Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2016.1

Case Scenario

- A 15-year-old female presents for septoplasty with her mother, appearing calm but nervous about her first surgery. In the preoperative area, she declines anxiolytics and engages in discussions with the anesthesiologist, who obtains consent. However, once in the operating room (OR), she panics and refuses to move to the OR table, stating she no longer wants the surgery. The surgical team is not present yet, and the anesthesiologist faces a decision. Should he insist she transfer to the table, remind her of her mother’s consent, and her initial agreement, or respect her refusal and take her back to the preoperative area?

- Inducing anesthesia on a clear-minded adolescent who is refusing surgery raises ethical concerns.

- The surgeon likely has several surgeries booked that day, or other cases are scheduled in that room. Going back to the preoperative area and having a multidisciplinary discussion with the patient and her mom will delay the start of the case and subsequent cases. This will affect other patients whose care is now delayed.

- Bringing a panicking 15-year-old through the preoperative area exposes other pediatric patients awaiting surgery to the anxiety that surgery/anesthesia can cause. This may affect how other patients feel and cause increased anxiety for those patients.

- Same-day surgery cancellation imposes financial costs on the surgical center or hospital.

- Though this is an elective surgery, the patient’s noisy breathing must be affecting her life in some capacity, so delaying surgery delays fixing the problem. This experience may also affect the patient in a way that future surgeries/anesthetics are feared.

- Lewis et al. surveyed pediatric anesthesiologists to determine their actions when faced with adolescent dissent. Of the respondents, 45% reported having canceled a case due to adolescent patient refusal during their career. Similarly, only 2% of respondents felt comfortable using physical restraints for a child older than 11 years, with 12 years being the average age that anesthesiologists felt that the adolescent’s refusal should halt a procedure.2

The Law and Parental Consent

- When raising children, parents are viewed as partners by the State. This partnership aims to achieve similar goals; society relies on developing healthy, responsible, and successful individuals, making it in the State’s best interest to ensure good access to healthcare for children.

- As a result, the law supports ensuring that parents make reasonable and safe decisions regarding medical care. One controversial example of government involvement is childhood vaccination requirements before school entry. Another instance occurs when a child is determined to be in danger, whether from an abusive environment or medical neglect.

- Progression of societal and cultural norms has created a need to modernize medical care and legal practices. Topics such as contraception, abortion, and mental health remain controversial, and many individuals feel that access to appropriate treatment is lacking. Additionally, younger generations are increasingly exploring these issues, often feeling uncomfortable discussing sensitive topics with their parents. While many agree that preventing unwanted teen pregnancies is beneficial for both individuals and society, teens may face obstacles in accessing contraception due to parental refusal or lack of knowledge.

- For instance, in Ohio, “statutory exceptions” allow minors to consent to certain medical treatments. These exceptions include:3

- Consent for an examination to gather physical evidence of an alleged sexual offense, such as rape

- Diagnosis or treatment of any venereal disease by a licensed physician

- Diagnosis or treatment for conditions believed to result from drug abuse or alcohol

- Consent for an HIV test for diagnosing AIDS or related conditions

- Donation of blood to a nonprofit voluntary program (if the individual is at least 17 years old)

- Receiving mental health treatment (if the individual is at least 14 years old) for a limited number of sessions or outpatient services, except for medication

- Receiving an abortion after applying to the local juvenile court, which can grant permission to bypass parental notification if it finds “good cause.”

- A parent or legal guardian usually consents to a minor’s evaluation and treatment, but there are three exceptions: emancipation, the mature-minor exception, and specific medical conditions.4

- A minor may be considered emancipated if they are married, self-supporting, living independently, or on active military duty. In some states, pregnant minors or those with children are also considered emancipated. Emancipated minors can consent to their own medical treatment.4

- Mature-minor exception applies to minors (typically aged 14 years and older) who can demonstrate maturity and understanding of their medical condition and treatment options. A physician’s assessment or a judicial declaration is needed to confirm this capability.4

- In specific cases like mental health services, substance abuse treatment, contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, and pregnancy-related care, minors may receive evaluation and treatment without parental consent. The rules regarding these exceptions vary by state, so professionals should consult state laws.4

Recommendations

- Each clinical situation is unique, and every minor should be treated as an individual with distinct needs. The main principle behind these decisions should be to act in the patient’s best interest, which involves fostering a sense of autonomy and empowerment.

- Clinicians should apply the rule of 7s and ensure that a minor can assent to medical decisions. To confirm that the minor fully understands the situation, they should be able to explain the plan and its importance in their own words.

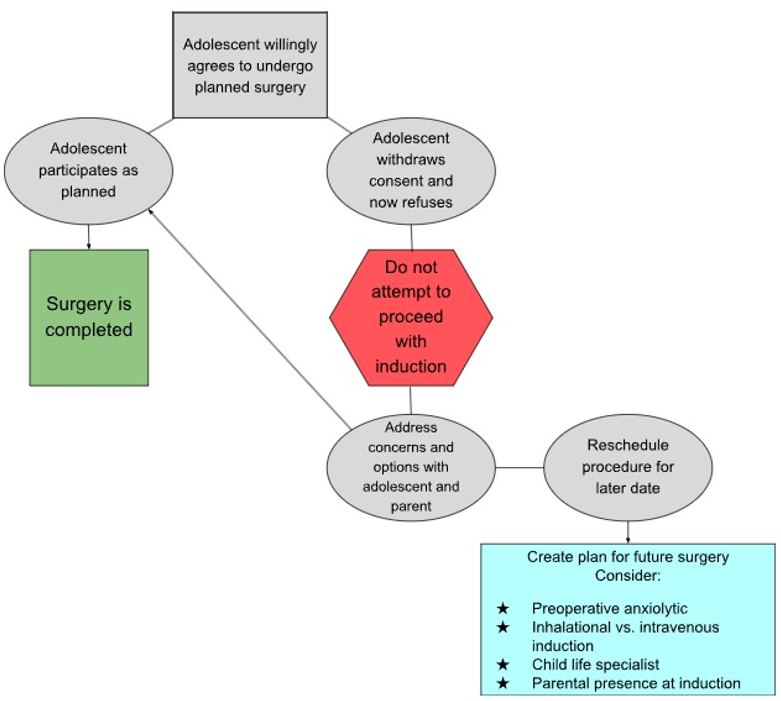

- Recommendations for handling medically necessary, nonemergent cases are outlined in Figure 1 below, aligned with the American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement on decision-making in pediatric patients, published in 2016.2

Figure 1. Flowchart for cases when adolescents withdraw assent. Adapted from Bryant BE et al. “You can’t make me!” Managing adolescent dissent to anesthesia. Pediatr Anaesth. 2021; 31:397–403.2

References

- Katz AL, Macauley RC, Mercurio MR, et al. Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2016; 138 (2): e20161485. PubMed

- Bryant BE, Adler AC, Mann DG, et al. “You can’t make me!” Managing adolescent dissent to anesthesia. Pediatr Anaesth. 2021; 31:397–403. PubMed

- Glyptis P. Most minors need parental consent for medical treatment. Ohio Bar. Published 15 Apr. 2016, Accessed 22 Oct 2024. Link

- Sirbaugh PE, Diekema DG. Consent for Emergency Medical Services for Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011; 128 (2): 427-433. Link

Other References

- Chatterjee D. “You Can’t Make Me!” Managing adolescent dissent to anesthesia. Pediatric Anesthesia Podcast. 2021. Accessed October 10, 2024. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.