Copy link

Pectus Excavatum

Last updated: 03/21/2025

Key Points

- Pectus excavatum is a common chest wall deformity characterized by a concave sternum creating a depression of the chest wall.

- Surgical correction is possible either through open or minimally invasive repair, the latter of which is more common.

- A thorough preoperative evaluation should be performed to assess each patient’s cardiac and pulmonary status prior to surgery.

- Postoperative pain is the most common factor influencing a patient’s length of stay.

- Thoracic epidurals have historically been the most common choice to treat pain. However, cryoablation has emerged as an alternative strategy for postoperative pain control.

Introduction

- Pectus excavatum is the most common congenital chest wall deformity. It is characterized by the sunken appearance of the sternum, causing concavity of the chest (Figure 1).

- Most cases are idiopathic, although it is associated with some conditions, such as Marfan’s syndrome and other connective tissue disorders.

- Pectus excavatum most commonly presents in males, with a male-to-female ratio of 4:1.1

- The clinical presentation depends on the severity of the defect. If a minimal defect is present, children may be asymptomatic.

- Symptoms are mainly related to the compression of the thoracic cavity, affecting cardiac and pulmonary physiology. Common symptoms include exercise intolerance, shortness of breath, palpitations, and chronic chest pain.2,3

Figure 1. Chest picture of an adolescent affected by a moderate/severe form of pectus excavatum. Written consent was obtained from the patient and the patient’s parents for publication of this image. Source: Pediatr Rep. 2013;5(3): e15. Link

Surgical Indications and Work-Up

- Surgical intervention is typically performed in the adolescent and teen years before skeletal maturity and prior to their pubertal growth spurt to ensure proper healing and continued growth after the intervention.

- While there is not a set of standard guidelines for intervention, common indications include a combination of the following:2

- Cosmetic dissatisfaction

- Exercise intolerance

- Cardiac and/or pulmonary compression

- Restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing

- Haller index of 3.25 or greater

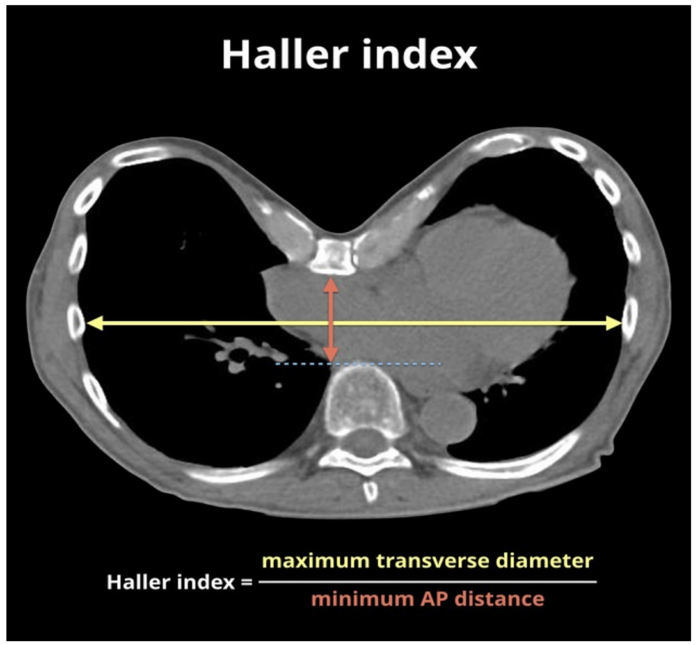

- The Haller index is a measurement used to help gauge the severity of pectus excavatum. It is calculated using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the chest, creating a ratio of the maximum transverse diameter over the anterior to posterior diameter at the point of highest concavity (Figure 2).

- If the Haller index is greater than 3.25, surgical intervention may be indicated.2,3

- In addition to a standard electrocardiogram to evaluate for electrical arrhythmias, patients should also receive a transthoracic echocardiogram to evaluate for other common sequelae of PE, including mitral valve prolapse secondary to compression of the mitral valve annulus, right ventricular compression or outlet tract obstruction, and aortic root dilation.2

- If pulmonary function testing is obtained, a restrictive pattern may be present with a reduced total lung capacity and forced vital capacity but increased forced expiratory volume.3

Figure 2. Technique for measuring Haller index on CT of the chest. Source: Gaillard F, Haller index. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 02 Dec 2024) Link

Surgical Approaches to Repair

- Pectus excavatum can either be corrected via open surgery, known as the Ravitch repair, or via a minimally invasive approach, known as the Nuss procedure or MIRPE (minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum).1

- Ravitch repair

- This open surgical procedure involves a sternal incision to manually reposition the chest wall. Bars may be placed to aid in maintaining the shape of the chest wall while it heals.1

- An open approach may be necessary in cases of severe deformity or asymmetry.

- Nuss procedure/MIRPE

- The majority of cases are now performed using this approach. It involves a thoracoscopically assisted placement of transverse retrosternal bar(s) to support and lift the sternum.1

- Patients may require more than one bar to be placed to correct deformity.

- Bars typically stay in place for 2-4 years before removal. Removal too soon can lead to the recurrence of pectus deformity, while delaying removal may lead to challenging bar extraction due to bar ossification.2

- Given that the bars remain in place for an extended period of time, it is important to consider metal allergy, bar displacement, and infection as potential complications.2

Anesthetic Considerations

Preoperative Considerations

- It is important to review relevant imaging prior to treating a patient with PE to assess the severity of the defect and its impact on the cardiac and pulmonary systems.

- As mentioned earlier, patients often have an echocardiogram prior to surgical intervention. An exercise stress test could also be considered prior to surgery if the defect is severe.1

- Premedication strategies exist to combat postoperative pain early.

- Gabapentin prior to surgery has been shown to be effective in reducing opioid use as well as postoperative pain scores.1,3

- Benzodiazepines may also play a role in decreasing postoperative pain scores.3

Intraoperative Considerations

- Monitors

- If the patient is found to have significant cardiopulmonary sequela during perioperative evaluation, invasive blood pressure monitoring with an arterial line should be considered.

- Transesophageal echocardiogram may be a useful tool intraoperatively if the patient is known to have significant cardiac compression to allow for close volume assessment and cardiac function during the procedure.3

- Access

- Large bore vascular access should be secured due to the potential risk of hemorrhage.

- Airway

- Lung isolation is normally indicated to allow for optimal visibility during the cryoablation portion of the procedure.

- Single lung ventilation can be achieved using either a double-lumen tube (DLT) or bronchial blocker.

- Placement of DLT can be difficult in younger and smaller patients, so a bronchial blocker may be favorable in these cases. Placement should be confirmed with a fiberoptic scope.4

- Maintenance

- Cases are performed under general anesthesia with an inhalational agent or total intravenous anesthesia.

- Nitrous oxide is contraindicated in these procedures due to the risk of expanding pneumothoraxes that could be created as a result of the surgical technique.3

- Emergence

- Deep extubation can be considered to limit coughing during emergence.3

Postoperative Considerations

- Postoperative concerns include postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and pain associated with the procedure.

- Sixty percent of patients have been shown to have PONV after pectus excavatum repair. It is important to treat PONV early using common antiemetics such as ondansetron, dexamethasone, and a scopolamine patch.3

- Pain can be severe regardless of surgical approach. Patients are typically admitted following surgery to help manage pain, and it is a significant contributor to hospital length of stay.2

- Many strategies exist to target pain:

- Thoracic epidurals

- Thoracic epidurals have historically been the most common choice for addressing pain related to surgical correction.

- Epidurals are placed in the T3-T6 region to provide pain control during surgery and postoperative period. However, they can be difficult to place and lead to longer hospital stays and delayed ambulation.1,3

- Cryoablation

- Cryoablation is becoming a popular choice for pain control following surgery. It requires isolated lung ventilation and is performed during the surgery, which can prolong intraoperative time.1,3

- Bilateral intercostal nerves 3-7 are targeted to provide adequate coverage.5

- The first intercostal nerve is excluded to avoid the potential for Horner’s syndrome.4

- Overall, cryoablation leads to shorter hospital stays, decreased opioid requirements, and faster ambulation.3

- The onset of relief may take up to 24 hours, so it is important to be proactive in treating pain in the immediate postoperative period.3

- Patient-controlled analgesia, regional nerve blocks, and multimodal pain medications are all options to consider for managing pain in the early postoperative phase while cryoablation begins to take effect.5

- Intercostal nerves typically regenerate in 4-6 weeks, providing long-lasting pain relief.3,5

- Regional anesthesia

- Different regional blocks have been considered to cover pain following surgical repair. The most common blocks include the erector spinae plane block, the paravertebral block, and the serratus anterior block.

- Regional blocks are generally not the first choice for pain control as they need to be performed bilaterally and have variable efficacy.2

- Multimodal analgesia

- Multimodal analgesia strategies are often used alongside the options listed above. Medication classes include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, gabapentinoids, steroids, N-methyl D-aspartate antagonists, and alpha-2 agonists.5

- It is common for patients to have a continuous opioid infusion pump on the day of surgery, especially when waiting for cryoablation to take effect.3

- Dexmedetomidine specifically has been seen to decrease emergence delirium and pain scores.3

- Thoracic epidurals

References

- Ghafoor T, Edsell M, Hunt I. Anaesthesia for the surgical correction of chest wall deformities. BJA Educ. 2020;20(8):287-93. PubMed

- Scalise PN, Demehri FR. The management of pectus excavatum in pediatric patients: a narrative review. Transl Pediatr. 2023;12(2):208-20. PubMed

- Brussels AR, Kim MS. Perioperative considerations in anesthesia for minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum, Nuss procedure. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2024;33(5):151459. PubMed

- McCoy N, Hollinger L. Cryoanalgesia and lung isolation: A new challenge for the Nuss procedure made easier with the EZ-Blocker™. Front Pediatr. 2021; 9:791607. PubMed

- Chiu M, Li R, Koka A, Demehri F. Pain management after pediatric minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum: A narrative review. Translational Pediatrics. 2024;13(12):2267-81. PubMed

Other References

- Ambardekar A. Pectus excavatum. OA Pediatric Vodcast. June 2022. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.