Copy link

Noonan Syndrome

Last updated: 04/23/2025

Key Points

- Noonan syndrome is a genetic condition with characteristic features that evolve over time, such as wide-set eyes, low-set ears, short neck, and short stature. Anatomic abnormalities such as micrognathia, shorter neck, and pectus deformities can present increased airway and ventilation difficulties.

- Congenital heart defects are common and include pulmonic valve stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and atrial/ventricular septal defects. Noonan syndrome is the second most common syndromic cause of congenital heart disease after Down syndrome.

- Additional anesthetic considerations include coagulopathies, musculoskeletal issues, and increased risk of malignant hyperthermia in a certain subset of patients.

Introduction

- Noonan syndrome is a genetic condition that affects multiple organ systems, often presenting with a combination of physical, developmental, and medical challenges. Often, there are no clinical manifestations at birth. Distinctive physical features, including a broad forehead, wide-set eyes, a short neck, and low-set ears, usually manifest starting in early childhood.1

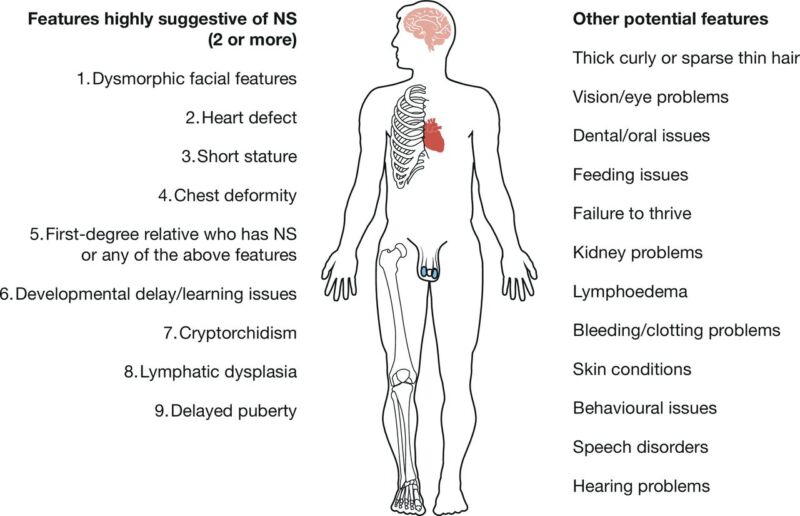

Figure 1. Common clinical features of Noonan syndrome. Source: Zenker M, et al. Arch Dis Child. 2022.2 CC BY SA 4.0.

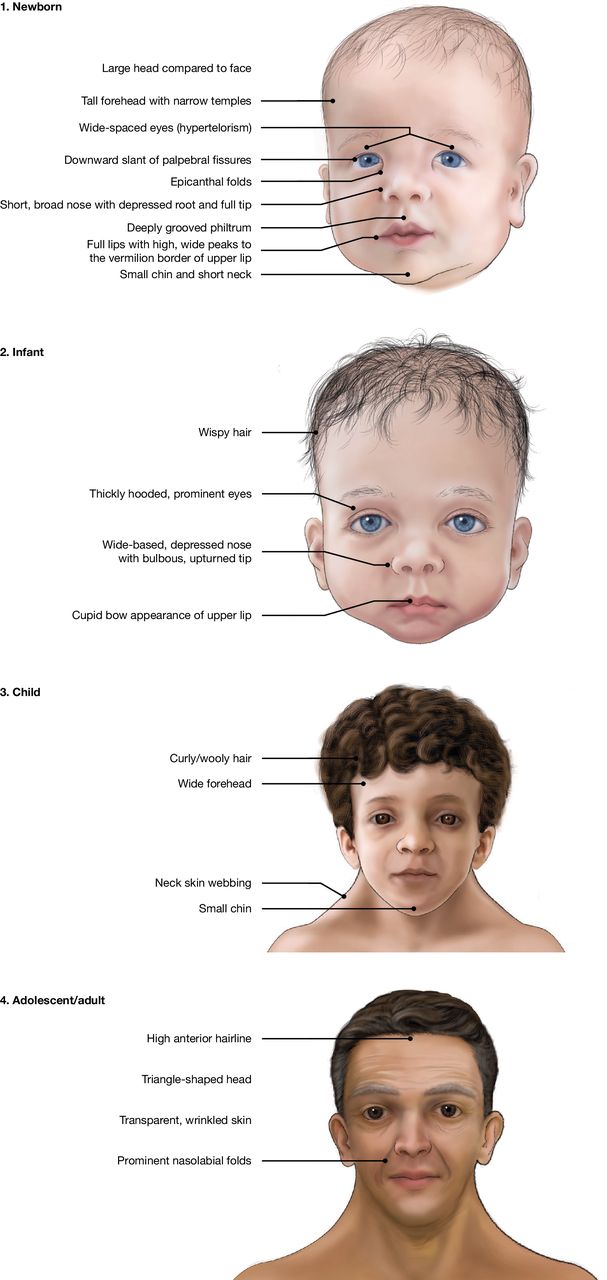

Figure 2. Characteristics of individuals with Noonan syndrome over time. Public domain images from the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

- Growth delays are common in those with Noonan syndrome, with many affected individuals having short stature. While some individuals may experience mild to moderate intellectual disabilities, cognitive function is often within the normal range, and people with Noonan syndrome can achieve developmental milestones at their own pace.

- Heart defects are one of the most common and serious aspects of the condition, with structural heart problems, such as pulmonary valve stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and atrial/ventricular septal defects, being prevalent in affected individuals.2 These cardiac issues may require ongoing monitoring and treatment, impacting long-term health.

Etiology

- Noonan syndrome is part of a group of disorders known as RASopathies, which result from mutations in genes involved in the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway, a key pathway that regulates cell growth, differentiation, and survival. Other common RASopathies include cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, Costello syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), and LEOPARD syndrome.1

- Noonan syndrome is linked to mutations in several genes involved in the RAS/MAPK signaling pathway, with the PTPN11 gene being the most frequently implicated (around 50% of Noonan diagnoses).3 It is a pleomorphic autosomal dominant inherited disease, although it can commonly arise from de novo mutations and has been associated with advanced maternal age.

Anesthetic Considerations

- Anesthetic management of patients with Noonan syndrome requires special consideration due to the variety of anatomic and physiologic challenges associated with the condition. Key anesthetic concerns include the following:

Cardiovascular Issues

- One of the most significant anesthetic concerns for individuals with Noonan syndrome is the presence of congenital heart defects, which are common in this population. In fact, Noonan syndrome is the second most common syndromic cause of congenital heart disease after Down syndrome.4 The most frequently encountered heart abnormalities include:

- Pulmonic valve stenosis (PS)

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

- Atrial septal defect (ASD)

- Ventricular septal defect (VSD)

Management Tips

- Preoperative: In addition to the usual preanesthetic assessment, a thorough cardiac evaluation, including an electrocardiogram and echocardiogram, should be performed to assess for any structural heart defects, valve function, and overall cardiac function.

- Intraoperative: Anesthetic considerations and hemodynamic goals depend on the patient’s congenital heart defect. Depending on the severity of the defect, invasive blood pressure monitoring via an arterial line or central line may also be warranted.

- PS:

- Heart rate, contractility, preload, and afterload should be maintained to promote adequate right-sided cardiac output and pulmonary perfusion.

- Pulmonary vascular resistance should be maintained by avoiding hypoxia, hypercapnia, and high peak airway pressures.

- HCM:

- Heart rate and contractility should be low or maintained.

- Preload and afterload should be high or maintained.

- ASD/VSD:

- Careful attention should be exercised while administering IV medications to prevent air embolism.

Airway Management

- Many patients with Noonan syndrome have physical features that can complicate airway management and make intubation/ventilation more challenging. These include

- Triangular facies

- Micrognathia

- Short neck

- Cervical spine abnormalities

- Pectus chest deformities

Management Tips

- Preoperative: It is important to assess the airway anatomy carefully and be ready to utilize fiberoptic intubation or other advanced airway techniques as needed. Infants with Noonan syndrome can have feeding difficulties, reflux, recurrent vomiting, and failure to thrive, which may necessitate a rapid sequence induction.

- Intraoperative: Extra attention should be given to positioning the patient during induction to optimize airway access and minimize potential complications. Furthermore, given altered lung volumes from chest deformities, anticipate possible ventilatory challenges.

Coagulopathies

- Some individuals with Noonan syndrome may have associated monocytosis, thrombocytopenia, and myeloproliferative disorders. This may require additional consideration in patients undergoing procedures where bleeding is a concern.

Management Tips

- Preoperative: It is highly recommended to obtain a full complete blood count, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time tests, and assess results for any signs of coagulopathy or abnormal bleeding, since bleeding disorders have been reported in up to 89% of cases.

- Intraoperative: Estimated blood loss should be closely monitored during surgery, and appropriate interventions (such as administering blood products) should be readily available if needed. Any neuraxial interventions should also be carefully considered in the setting of the patient’s coagulation studies.

Musculoskeletal Considerations

- Some patients with Noonan syndrome may experience musculoskeletal issues, such as joint contractures, scoliosis, or hypermobility. These conditions can complicate positioning on the operating table and potentially increase the risk of nerve damage during surgery.

Management Tips

- Preoperative: Identifying musculoskeletal limitations and planning for safe positioning during surgery is important.

- Intraoperative: Extra care should be taken during positioning to avoid unnecessary stress on joints and the spine, and to minimize the risk of nerve injury.

Malignant Hyperthermia Risk

- While most patients with Noonan syndrome are not at an elevated risk of malignant hyperthermia (MH), there are some patients with a specific diagnosis of “Noonan-like syndrome” (SHOC2 S2G mutation) who may be at elevated risk for MH.5

- These individuals may present with loose anagen hair, myopathy, normal to moderately elevated creatine kinase levels and HCM. In these cases, extra care should be exercised to avoid administering triggering anesthetic agents, including all inhaled anesthetics (except nitrous oxide) and succinylcholine.6 A complete flush of the anesthesia machine to eliminate residual inhaled volatile anesthetics should be performed and charcoal filters should be used to further reduce the risk of exposure to triggering agents.

References

- Allen MJ, Sharma S. Noonan Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Jan 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Link

- Zenker M, Edouard T, Blair JC, Cappa M. Noonan syndrome: improving recognition and diagnosis. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2022;107(12): 1073-8. PubMed

- National Human Genome Research Institute. About Noonan syndrome. Genome.gov. Published 2013. Link

- Roberts AE, Allanson JE, Tartaglia M, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome. The Lancet. 2013;381(9863):333-42. PubMed

- Ramos J, Laochamroonvorapongse D. Noonan Syndrome: Clinical Features and Considerations for Anesthetic Management. Society for Pediatric Anesthesia News. 2017; 30(4). Link

- Safe and Unsafe Anesthetics - MHAUS. www.mhaus.org. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.