Copy link

Nonobstetric Surgery in Pregnancy

Last updated: 10/16/2023

Key Points

- No currently used anesthetic agents have been shown to have any teratogenic effects in humans when used in standard concentrations at any gestational age.

- A pregnant patient should never be denied medically necessary surgery or the surgery be delayed because this can adversely affect the pregnant patient and the fetus.

- Obtaining an obstetric consultation before performing nonobstetric surgery is critical to optimize maternal-fetal well-being.

- Avoiding hypotension, hypoxia, hypercarbia, or hyper/hypothermia is critical for both fetal and maternal well-being.

- Extra care must be taken when instrumenting the airway of a pregnant patient and nasal intubation is not recommended.

Introduction

- Nonobstetric surgery may be required at any trimester during pregnancy, which carries the unique challenge of balancing maternal and fetal physiology.

- Understanding the physiological changes of pregnancy enables safe delivery of anesthesia. Both obstetric and neonatal consultations are critical to the patient’s care, regardless of the type of surgery or procedure.

- Urgent or emergent surgery should never be denied to pregnant patients. However, elective surgeries should be postponed until 6 weeks postpartum.1

First Trimester (Weeks 1-12)

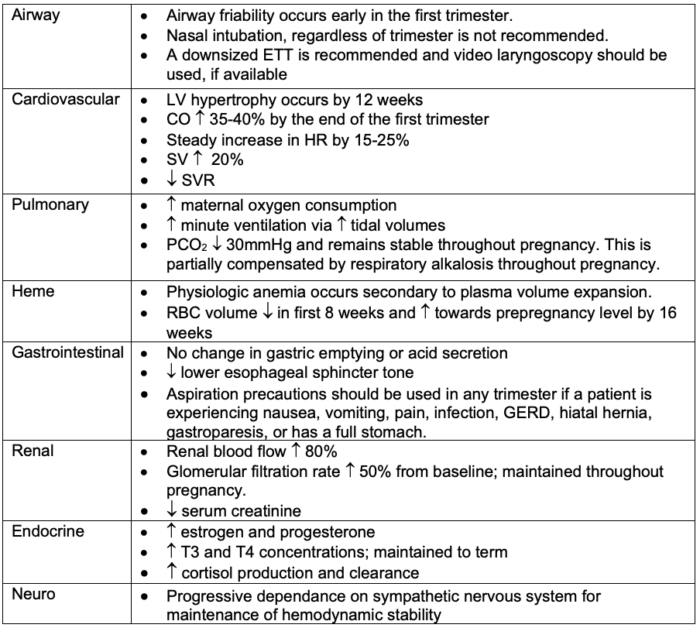

Maternal Physiologic Considerations (Table 1)

Table 1. Maternal physiological considerations during the first trimester of pregnancy

Abbreviations: ETT, endotracheal tube; LV, left ventricular; CO, cardiac output; HR, heart rate; SV, stroke volume; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; RBC, red blood cell; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease

Fetal Considerations

• There is no conclusive link between anesthetic agents and fetal teratogenesis.

• Benzodiazepines in limited quantities can be safely offered without concern for cleft palate.2

• Major embryonic development is complete by the eighth week of gestation; however, neurologic and pulmonary development are ongoing.1-5

• Prolonged hypotension, hypoxia, hypercarbia, or hyper/hypothermia should be avoided.2,3

Second Trimester (Weeks 13-26)

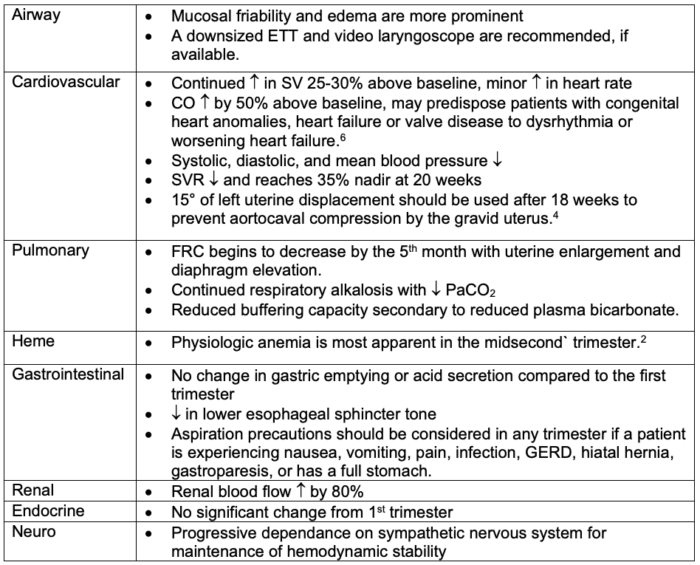

Maternal Physiologic Considerations (Table 2)

Table 2. Maternal physiological considerations during the second trimester of pregnancy

Abbreviations: ETT, endotracheal tube; CO, cardiac output; SV, stroke volume; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; FRC, functional residual capacity; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease

Fetal Considerations

- The second trimester is preferred for non-elective surgery as patients are considered to be at the lowest risk for preterm delivery.4,5

Third Trimester (Weeks 27-40)

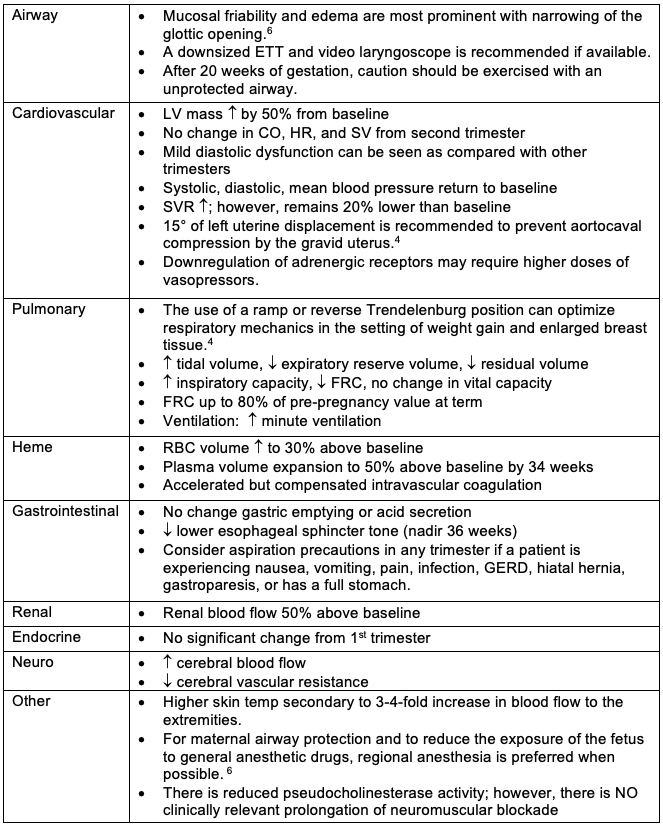

Maternal Physiologic Considerations (Table 3)

Table 3. Maternal physiological considerations during the third trimester of pregnancy

Abbreviations: ETT, endotracheal tube; LV, left ventricular; CO, cardiac output; HR, heart rate; SV, stroke volume; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; FRC, functional residual capacity; RBC, red blood cell; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease

Fetal Considerations

- Once the fetus is viable, corticosteroid administration should be considered to facilitate fetal lung maturity and should be discussed with a consulting maternal-fetal medicine provider.1

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications should be avoided after 32 weeks of gestation secondary to concerns for premature patent ductus arteriosus closure.3

Anesthetic Considerations

- Maternal airway

- The risk of difficult intubation and difficult mask ventilation is increased. Loss of airway control is the most common cause of anesthesia-related maternal mortality.7,8 The authors recommend utilizing video laryngoscopy whenever available.

- Advanced airway devices should always be readily available.2

- A downsized ETT is recommended. Nasal intubation is NOT recommended at any stage.

- Mallampati classification is more predictive of difficult intubation in pregnancy than in nonpregnant patients and the incidence of class IV airways is increased by 34% in pregnant patients.2

- Please review the Obstetric Anaesthetist’s Association and Difficult Airway Society recommendations for the difficult obstetric airway. Link

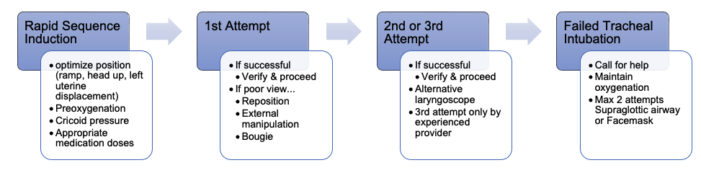

Figure 1. Management of the difficult and failed tracheal intubation in a pregnant patient

- Sedative effects of all anesthetics may be observed at lower doses than in nonpregnant patients, thus decreasing minimum alveolar concentration requirements.4

- A 2019 Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology consensus statement recommended against the use of sugammadex during pregnancy in nonemergent circumstances, secondary to concerns of progesterone binding.9

- Fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring can be useful in optimization of maternal positioning and hemodynamics; however, there is no consensus on how and when fetal monitoring should be done and may be guided by institutional protocols. Intraoperative fetal monitoring has not shown an improvement in maternal or fetal outcomes.4

- General guidelines for FHR monitoring are as follows.1

- If the fetus is previable, the FHR can be measured by Doppler before and after the procedure.

- If the fetus is viable, electronic FHR and contraction monitoring should be performed before and after the procedure.

- Intraoperative electronic FHR monitoring may be appropriate when all of the following apply.

- The fetus is viable.

- Intraoperative electronic FHR is physically possible.

- An obstetric care provider with cesarean delivery privileges is readily available.

- The pregnant patient has provided informed consent for emergency cesarean delivery, if needed.

- The planned surgery will allow the safe interruption to perform emergency cesarean delivery.

References

- ACOG Committee. Opinion No. 775: Nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 133(4): e285-6. PubMed

- Reitman E, Flood P. Anaesthetic considerations for non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy. Br J Anaesth. 2011; 107(S1): i72-8. PubMed

- Upadya M, Saneesh PJ. Anaesthesia for non-obstetric surgery during pregnancy. Indian J Anaesth. 2016; 60: 234-41. PubMed

- Haggerty E, Daly J. Anaesthesia and non-obstetric surgery in pregnancy. BJA Educ. 2021;21(2):42-3. PubMed

- Okeagu CN, Anandi P, Gennuso S, et al. Clinical management of the pregnant patient undergoing non-obstetric surgery: review of guidelines. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020; 34: 269-81. PubMed

- Kacmar RM, Gaiser RG. Physiologic changes of pregnancy. In: Chestnut DH, Wong CA, Tsen LC et al., editors. Chestnut’s obstetric anesthesia: principles and practice. 6th Ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019.13-37

- Mushambi MC, Kinsella SM, Popat M, et al. Obstetric Anaesthetists’ Association and Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 2015; 70: 1286-306. PubMed

- Hawkins JL, Chang J, Palmer SK, et al. Anesthesia-related maternal mortality in the United States: 1979–2002. Obstet Gynecol. 2011; 117: 69–74. PubMed

- Willett, et al. Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology. Statement on sugammadex during pregnancy and lactation. Published April 22, 2019. Accessed October 16, 2023. Link

Other References

- Daly J. Managing the pregnant patient for nonobstetric surgery. A PBLD approach. OA-SOAP Fellows Webinar Series, 2020. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.