Copy link

Neuropathic Pain: Treatment

Last updated: 02/13/2024

Key Points

- Tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and gabapentinoids should be used as first-line treatment for neuropathic pain.

- Lidocaine patches, capsaicin patches, and tramadol are considered second-line treatments, and botulism toxin A and opioids are considered third-line treatments for neuropathic pain.

- Nonpharmacological therapies, including psychological and physical therapies, have been used effectively to treat neuropathic pain.

Introduction

- According to the International Association for the Study of Pain, neuropathic pain is a clinical description (not a diagnosis) of pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central or peripheral somatosensory nervous system.1

- Lesions or diseases of the somatosensory nervous system result in altered and disordered transmission of sensory signals to the spinal cord and brain. Common conditions associated with neuropathic pain include postherpetic neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, painful radiculopathy, human immunodeficiency virus infection, leprosy, amputation, central poststroke pain, etc.2

- Please see the OA summary on the etiology, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of neuropathic pain. This summary will focus on the treatment of neuropathic pain.

Treatment Approach

- The management of neuropathic pain focuses on managing the symptoms.2

- Patients with neuropathic pain typically do not respond to commonly used analgesics, such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or weak opioids (codeine).

- Usually, pharmacological and complementary therapies are used before interventional strategies. However, pharmacological treatments are effective in less than 50% of patients, and their side effects limit their clinical utility.2

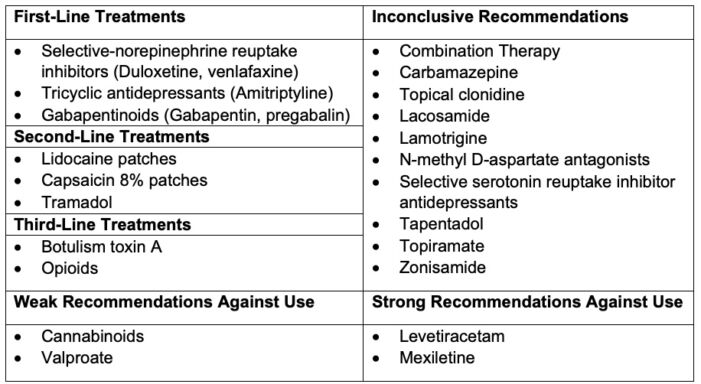

- In 2015, a special interest group of the International Association for the Study of Pain performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 229 studies and published recommendations for the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain3 (Table 1).

Table 1. Pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain

First-Line Treatments

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) should be used as first-line treatment for neuropathic pain.3

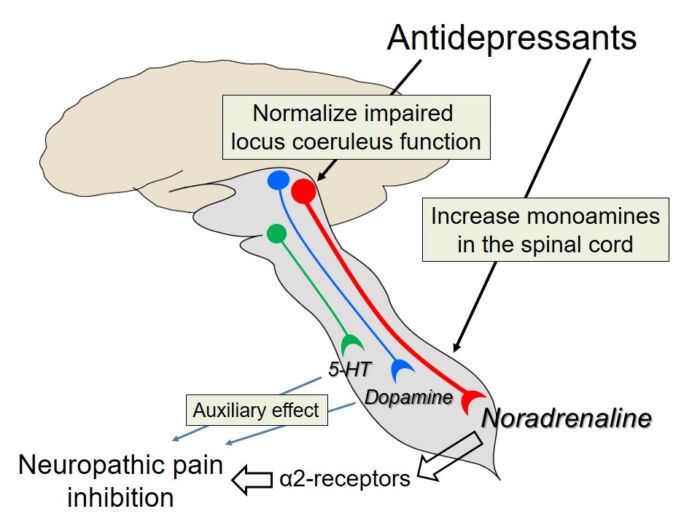

- TCAs and SNRIs inhibit the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin (5-HT), increasing their levels in the synaptic clefts. In the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, norepinephrine enhances analgesia through ɑ-2 adrenergic receptors by activating the impaired descending noradrenergic inhibitory pathways.4

- 5-HT and dopamine are thought to play less important roles than norepinephrine in the inhibition of neuropathic pain, but increased 5-HT and dopamine levels in the central nervous systems may enhance the inhibitory effects of norepinephrine in an auxiliary manner.4 Additionally, TCAs and SNRIs reactivate impaired locus ceruleus function.

- Of note, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are not effective for neuropathic pain.3

Figure 1. Common clinical syndromes causing peripheral neuropathic pain. Source: Obata H. Analgesic mechanisms of antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Int J Mol Sci. 2017; 8(11): 2483. Open Access.

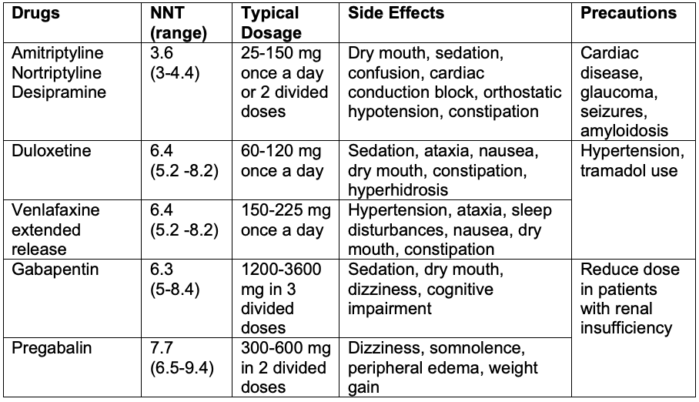

- The typical dosage and side effects of commonly used SNRIs and TCAs are listed in Table 2. Among the SNRIs, duloxetine is the most studied and commonly used.3

- TCAs generally have similar efficacy to SNRIs. Tertiary-amine TCAs (amitriptyline, imipramine, and clomipramine) are not recommended at doses greater than 75 mg/day in adults older than 65 years secondary to major anticholinergic and sedative side effects and the potential risk of falls.3 An increased risk of cardiac death has been reported with TCAs at doses greater than 100 mg/day.3

- Gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin) are antiepileptics and exert their analgesic effects by decreasing central sensitization through binding to the ɑ2δ subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channels and modulation of central nervous system gamma amino butyric acid activity. They are more effective for peripheral neuropathic pain than central etiologies.

- In patients with moderate or severe neuropathic pain from postherpetic neuralgia or painful diabetic neuropathy, oral gabapentin (1200-3600 mg/day for 4-12 weeks) was associated with pain reduction of at least 50% in 14-17% more patients than placebo.

- Other antiepileptics, carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, are used as first-line treatment for trigeminal neuralgia (See OA Summary on trigeminal neuralgia Link). Their mechanism of action is by blocking voltage-gated sodium channels.

- Gabapentin is typically started on a dose of 300 mg orally once daily on day 1, twice daily on day 2, three times daily on day 3, and increased by 300 mg daily. Pregabalin is structurally related to gabapentin and has a greater affinity for the receptor site. Dose escalation can be achieved faster than with gabapentin.

Table 2. First-line treatments for neuropathic pain. NNT refers to the number of patients necessary to treat to obtain one responder with more than 50% pain relief.2,3

Second-Line Treatments

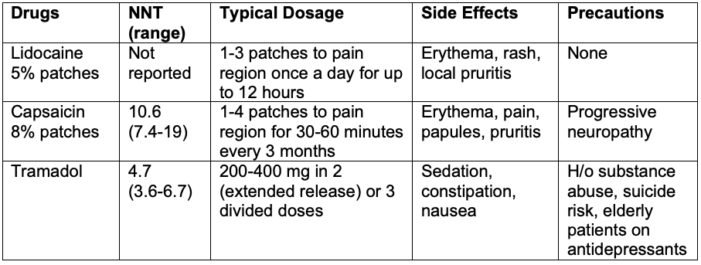

- Lidocaine patches, capsaicin patches, and tramadol are considered second-line treatments.3

- Lidocaine acts by blocking sodium ion channels and thereby blocking action potentials. Capsaicin is a highly selective agonist of the transient receptor potential vanilloid receptor, subtype 1 (TRPV1) channel, leading to a decrease in nociceptive fiber firing activity. Capsaicin is an effective and well-tolerated treatment in patients with postherpetic neuralgia, peripheral nerve injury, and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. In the United States, capsaicin is only approved for postherpetic neuralgia6 (Table 3).

- Tramadol is a centrally acting, u-opioid receptor agonist with SNRI activity.3 There is an increased risk of seizures in patients with epilepsy or who are taking drugs that reduce the seizure threshold, such as TCAs. The potential for abuse and side effects, such as serotonin syndrome, should be weighed when considering its use.

Table 3. Second-line treatments for neuropathic pain. NNT refers to the number of patients necessary to treat to obtain one responder with more than 50% pain relief.2,3

Third-Line Treatments

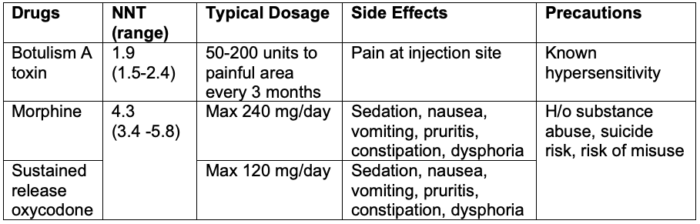

- Botulism toxin A, a potent neurotoxin that is commonly used to treat trigger points, has a beneficial role in the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain, such as diabetic neuropathic pain, postherpetic neuralgia, and trigeminal neuralgia.3

- Opioid agonists, such as oxycodone and morphine, are mildly effective. Maximum effectiveness has been associated with 180 mg morphine or equivalent, with no additional benefit with higher doses3 (Table 4). In addition to common side effects of opioids, other concerns include opioid-associated overdose, misuse, and diversion.

Table 4. Third-line treatments for neuropathic pain. NNT refers to the number of patients necessary to treat to obtain one responder with more than 50% pain relief.2,3

Nonpharmacological Therapies

- Psychological interventions, including relaxation techniques, hypnosis, cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) have been shown to improve outcomes. CBT is the most researched option and refers to a group of techniques that addresses mood (typically anxiety and depression), function (including disability), and social engagement.3

- Physical interventions, such as physical therapy, exercise, and movement representation techniques (mirror therapy), are beneficial for neuropathic pain.3 Other options include transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acupuncture.

Interventional Therapies

- Interventional therapies provide alternative treatment strategies in patients with refractory neuropathic pain.2 A few options are listed below.

- Epidural steroid injections for cervical and lumbar radiculopathies

- Sympathetic ganglion blocks for complex regional pain syndrome

- Spinal cord stimulation

- Dorsal root ganglion blocks

- Epidural and transcranial cortical neurostimulation

- Deep brain stimulation

- Intrathecal morphine and ziconotide (an N-type calcium channel antagonist)

References

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. International Association for the Study of Pain Terminology Working Group. Definition of pain. IASP. Publish date 1994. Updated 2022. Accessed December 28th, 2023. Link

- Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017; 3:17002. PubMed

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2): 162-73. PubMed

- Obata H. Analgesic mechanisms of antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Int J Mol Sci. 2017; 8(11): 2483. PubMed

- Moore A, Derry S, Wiffen P. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain. JAMA. 2018; 31998): 881-9. PubMed

- Burness CB, McCormack PL. Capsaicin 8% patch: A review in peripheral neuropathic pain. Drugs. 2016; 76(1): 123-34. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.