Copy link

Mitral Stenosis: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Symptomatology

Last updated: 12/11/2024

Key Points

- Mitral stenosis (MS) is most commonly caused by rheumatic disease with characteristic mitral commissural fusion, thickened and immobile mitral valve leaflets, and fibrotic, shortened, calcified chordae tendineae.

- There is an increased incidence of MS in aging patients due to mitral annular calcification (MAC).

- Reduction of the mitral valve area impedes flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle, resulting in an atrioventricular pressure gradient, elevated left atrial pressure, and pulmonary hypertension.

- Dyspnea is often the presenting symptom in MS, but fatigue, hemoptysis, chest pain, and signs of right-sided heart failure may also be present.

Etiology

- The etiology of MS is primarily rheumatic (85.4%), followed by degenerative (includes calcific) (12.5%), other (0.9%), endocarditis (0.6%), and congenital (0.6%).1

- Other rare causes include congenital deformities (e.g., parachute mitral valve, double orifice mitral valve), polysaccharidosis, multi-system diseases (e.g., Fabry disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis), and carcinoid syndrome.2

Epidemiology

- The prevalence of rheumatic heart disease is declining in high-income countries, with an incidence of about 1 in 100,000, compared with higher prevalence in low- and middle-income countries. In Africa, the prevalence of rheumatic heart disease is estimated at around 35 in 100,000.3

- The incidence of rheumatic MS is higher in females.3

- The Euro Heart survey prospectively collected data on moderate to severe native aortic and mitral valvular disease, and MS was the least common (12.1%) left-sided valvular disease compared to aortic stenosis (43.1%), aortic regurgitation (13.3%), and mitral regurgitation (31.5%).1

Pathophysiology

Rheumatic MS

- In rheumatic heart disease, there is an autoimmune response to a group A streptococcal infection, which affects the heart due to the similarity between streptococcal M protein and cardiac myosin. This results in ongoing inflammation of the heart valves long after the initial rheumatic fever episode and is compounded by hemodynamic stresses over time, resulting in rheumatic MS.2

- The main pathological changes of the mitral leaflets in rheumatic MS are:

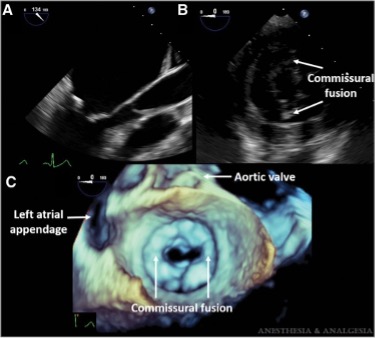

- Leaflet thickening, nodularity, and commissural fusion (Figure 1) result in a narrowing of the mitral valve area.

- Leaflets may be calcified.

- Chordae may also be fused and shortened.

- These changes may also lead to poor leaflet coaptation and resultant mitral regurgitation. This mechanism of mitral regurgitation is described as Type III dysfunction per Carpentier’s classification system or restricted leaflet motion.

Figure 1. Rheumatic mitral stenosis. A: Midesophageal long-axis view of the mitral valve (MV) showing thickened leaflets. B: Transgastric basal short-axis view showing MV leaflets with commissural fusion. C, 3D en face view of the MV seen from the left atrium demonstrating commissural fusion. Used with permission from Cherry AD et al. Anesth Analg 2016.5

Degenerative MS

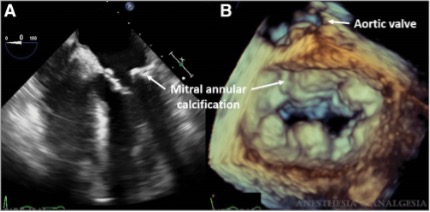

- In degenerative MS, MAC develops over time due to excess annular tension and trauma (Figure 2). It has been proposed that MAC reduces the normal annular dilation during diastole and impairs anterior mitral leaflet mobility, resulting in MS.4

Figure 2. Degenerative mitral stenosis. A: Midesophageal 4-chamber view showing extensive calcification of the mitral annulus. B: 3D en-face view of the mitral valve seen from the left atrium demonstrating calcification of the mitral annulus with relative sparing of the leaflets. Used with permission from Cherry AD et al. Anesth Analg. 2016.5

Disease Progression

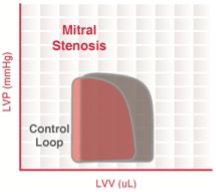

- As the mitral valve orifice narrows, a pressure gradient develops between the left atrium and left ventricle, resulting in elevated left atrial pressures, left atrial enlargement, and pulmonary congestion. As the severity of stenosis worsens, the flow restriction across the mitral valve limits left ventricular output. As a result, left ventricular end-diastolic volume and stroke volume decrease, with a reduction in cardiac output. Reduced ventricular filling also decreases ventricular wall stress, which may decrease ventricular end-systolic volume slightly. However, the net result is that end-diastolic volume decreases more than end-systolic volume, with an overall decrease in stroke volume (Figure 3).

- Increased left atrial pressures may cause postcapillary pulmonary hypertension and, over time, precapillary pulmonary hypertension/pulmonary arterial hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction.

- Up to one-third of patients with MS have also been found to have moderate to severe tricuspid regurgitation secondary to either rheumatic disease or severe pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Figure 3. Pressure-volume loop in mitral stenosis (red loop). Abbreviations: control loop in grey. LVV = left ventricular volume. LVP = left ventricular pressure. Source: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0. Link

Symptomatology

- Based on various parameters, including patient symptoms, valve anatomy, hemodynamic consequences on the left atrium, and pulmonary circulation, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) has recommended staging guidelines for MS.6

- The stages of MS as per the 2014 ACC/AHA guidelines6 are:

- Stage A: At risk of MS

- Stage B: Progressive MS

- Stage C: Asymptomatic severe MS

- Stage D: Symptomatic severe MS

- In mild disease, patients can be asymptomatic. As stenosis worsens, patients usually present with dyspnea, often during exercise or in the setting of situations that increase the heart rate or flow across the mitral valve. Other symptoms include fatigue, hemoptysis (from pulmonary venous hypertension leading to rupture of anastomoses between bronchial veins), and chest pain.

- The enlarged left atrium may impinge on the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, causing vocal cord paralysis and hoarseness, known as Ortner’s syndrome or cardiovocal syndrome.

- Atrial fibrillation occurs in 40-75% of patients who are symptomatic from MS. Occasionally, patients may first present with embolic sequelae from atrial fibrillation.

References

- Lung B, Baron, G, Butchart EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(13):1231-43. PubMed

- Chandrashekhar Y, Westaby S, Narula J. Mitral stenosis. Lancet. 2009;374(9697):1271-1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60994-6 PubMed

- Shah SN, Sharma S. Mitral stenosis. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Link

- Sud K, Agarwal S, Parashar A, et al. Degenerative mitral stenosis. Circulation. 2016;133(16):1594-1604. PubMed

- Cherry AD, Maxwell CD, Nicoara A. Intraoperative evaluation of mitral stenosis by transesophageal echocardiography. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(1):14-20. PubMed

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014; 129(23):2440-92. PubMed

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.