Copy link

Management of Pregnant Patients on Anticoagulation

Last updated: 10/10/2024

Key Points

- In obstetric patients receiving anticoagulation, the risk of bleeding and spinal epidural hematoma from neuraxial must be weighed against the risks inherent in general anesthesia.

- The recommended intervals between the last dose of thromboprophylaxis and neuraxial placement, catheter removal, and resumption of thromboprophylaxis depend on the drug used and its dose. These dosing intervals can minimize the risk of neuraxial placement in patients on anticoagulation.

- Multidisciplinary discussions between obstetrics, anesthesiology, and, if appropriate, hematology can help facilitate a safe plan for anticoagulation and neuraxial placement.

Introduction

- Pregnancy is a hypercoagulable state.

- Venous thromboembolism occurs in about 29.8/100,000 vaginal deliveries. Cesarean delivery has a four times higher risk of thromboembolism than vaginal delivery.1

- Embolism is the cause of 14.9% of maternal mortality in developed countries.2

- Thrombotic pulmonary embolism causes 9.3% of maternal mortality in the US.3

- Anticoagulation, either therapeutic or prophylactic, can be given to patients at an increased risk of developing thromboembolism.

Anticoagulation in Pregnancy

- The decision to start patients on thromboprophylaxis is complex and relies on various factors. The three components of a patient history considered are as follows:4,5

- History of venous thromboembolism (stratified by provoked versus unprovoked)

- Thrombophilia

- Low-risk thrombophilia: Factor V Leiden heterozygous; prothrombin G20210A heterozygous; protein C or protein S deficiency.

- High-risk thrombophilia: Antithrombin deficiency; factor V Leiden homozygous; prothrombin G20210A mutation homozygous; double heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A and factor V Leiden.

- Other risk factors

- Age older than 35 years, obesity, cesarean delivery, Black race, heart disease, sickle cell disease, diabetes, systemic lupus, tobacco use, and multiple pregnancy.

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) Guidelines6

- Therapeutic anticoagulation during pregnancy is recommended for patients with acute venous thromboembolism or those at high risk for venous thromboembolism (i.e., mechanical heart valve).

- Either prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation during pregnancy is recommended for patients with a history of thrombosis and patients at risk for venous thromboembolism.

- Patients at risk include, but are not limited to, those with thrombophilias, either acquired or inherited, and those with a history of idiopathic thrombosis.

- Thromboprophylaxis is recommended for hospitalized antepartum patients and patients at risk for venous thromboembolism after delivery.3

- Heparin products are preferred for anticoagulation in pregnancy.6

Pharmacokinetics in Pregnancy

- In pregnancy, there are changes in the pharmacokinetic profiles of heparins.

- One study found that when given a dose of subcutaneous unfractionated heparin (UFH), pregnant women in the third trimester had a lower peak plasma concentration than nonpregnant controls. Pregnant women had no significant increase in activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), unlike nonpregnant women whose aPTT increased.7

- Pregnant women who receive a single dose of UFH may not have the same response as the same dose given to nonpregnant women.

- Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is often used in pregnant patients due to better bioavailability and dosing predictability.1

- With enoxaparin, the measured antifactor Xa (anti-Xa) activity is the same at 8 hours postdose (1st/2nd trimester) and 6 hours postdose (3rd trimester) as it is 12 hours postdose in nonpregnant patients.

- ACOG Guidelines: Therapeutic LMWH should be dosed once or twice daily. UFH should be dosed every 12 hours.6

Spinal Epidural Hematoma Risk

- The risk of spinal epidural hematoma (SEH) is concerning in patients on anticoagulation.

- A systematic review of studies from 1952-2016 and the US Anesthesia Closed Claims Project Database from 1990-2013 found no case of SEH after obstetric neuraxial procedure in pregnant women receiving thromboprophylaxis.8

- The total number of these cases is unknown.

- Neither blood labs (aPTT, anti-Xa) nor viscoelastic testing (ROTEM, TEG) have been validated to assess the risk of SEH in obstetric patients on anticoagulation.1

Antepartum Management

- Multidisciplinary planning is critical in coordinating a safe anticoagulation and anesthesia plan.

- Patients taking LMWH in the last month of pregnancy or close to the time of delivery may be converted to UFH.

- This is due to the shorter time needed between the last UFH dose and neuraxial placement.

- If the patient has been on UFH for more than four days, they need a platelet count checked before neuraxial placement due to the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.1

- Another option is to stop therapeutic anticoagulation and induce labor within 24 hours.6

- The use of protamine to reverse heparin to facilitate obstetric neuraxial placement has yet to be studied.

Intrapartum Management1,9

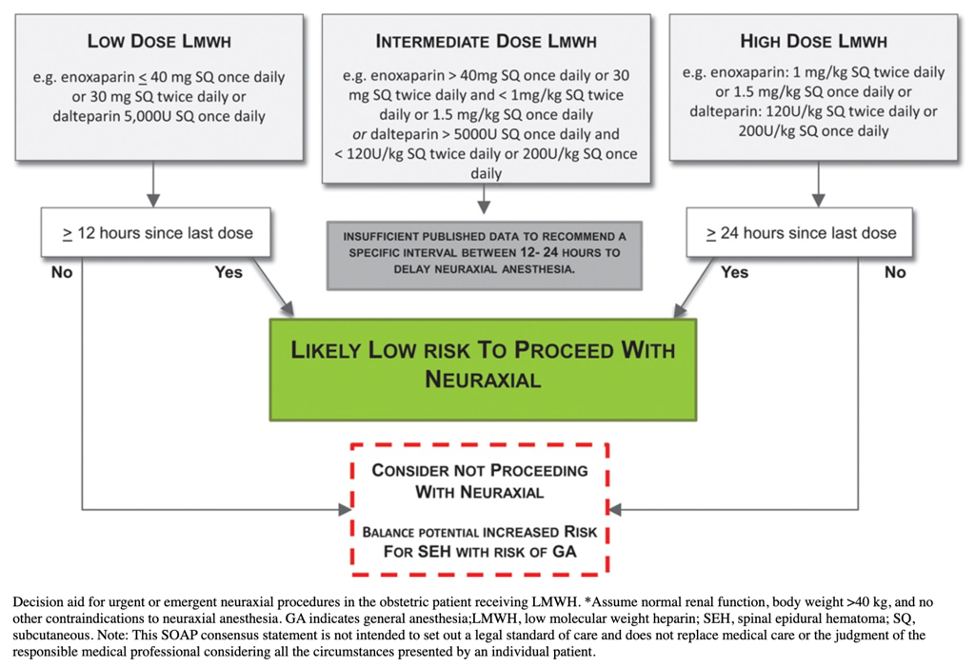

LMWH

- Low dose (Prophylactic dose): Enoxaparin ≤40 mg subcutaneously (SQ) once daily or 30 mg SQ twice daily

- Wait 12 hours since the last dose before neuraxial placement

- In urgent cases with patients with high-risk factors for general anesthesia, the risk of general anesthesia may be greater than the risk of SEH.

- Intermediate dose: Enoxaparin more than 40 mg SQ once daily/30 mg SQ twice daily and less than 1 mg/kg SQ twice daily/1.5 mg/kg SQ once daily

- There is insufficient evidence to recommend an interval between 12 and 24 hours before performing neuraxial anesthesia.

- High-dose (therapeutic dose): Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg SQ twice daily or 1.5 mg/kg SQ once daily

- Wait 24 hours from the last dose before neuraxial placement

- In urgent cases with patients with high-risk factors for general anesthesia, weigh the risk of general anesthesia against the risk of SEH.

Figure 1. Decision for urgent or emergent neuraxial procedures in the obstetric patient receiving LMWH. Used with permission from Leffert L et al. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(3):928-44.1

UFH

- Low dose (5,000 U SQ twice or three times daily): Consider waiting 4-6 hours since the last dose or assess coagulation status before neuraxial placement.

- In urgent cases, the risk of general anesthesia must be weighed against the risk of SEH from neuraxial. It may be appropriate to place neuraxial without delay.

- Intermediate dose (7,500 or 10,000 U SQ twice daily, total daily dose ≤ 20,000 U): Consider waiting 12 hours since the last dose and assess coagulation status before neuraxial placement

- In urgent cases, the risk of general anesthesia must be weighed against the risk of SEH from neuraxial. It may be appropriate to place neuraxial without delay.

- High dose (Individual dose >10,000 U SQ per dose or >20,000 U SQ daily): Consider waiting 24 hours before and assess coagulation status before neuraxial placement

- In urgent cases, if it is either less than 24 hours since the last dose or coagulation tests are unavailable, there is insufficient data to recommend proceeding with neuraxial.

- IV heparin: Stop the infusion for 4-6 hours and assess coagulation status before neuraxial placement

- A normal coagulation status would be aPTT within the normal range or an undetectable anti-Xa level.

Figure 2. Decision for urgent or emergent neuraxial procedures in the obstetric patient receiving UFH. Used with permission from Leffert L et al. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(3):928-44.1

Postpartum Management1,9

Starting or Resuming Thromboprophylaxis

- Low-dose LMWH:

- Wait at least 12 hours after neuraxial placement and at least four hours after catheter removal before starting or resuming, whichever is greater.

- Indwelling catheters can be kept on low-dose LMWH.

- The catheter should be removed at least 12 hours after the last dose, and the next dose should be given at least four hours after that.

- The addition of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in those with an epidural catheter and on thromboprophylaxis may increase the risk of bleeding complications.

- High-dose LMWH:

- Wait at least 24 hours after neuraxial placement and at least four hours after catheter removal before starting or resuming, whichever is greater

- Subcutaneous UFH prophylaxis:

- The recommendations vary by society. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA) guidelines consider both pregnant and nonpregnant individuals, while the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) consensus statement is written specifically for pregnant patients.

- ASRA: Medication can be resumed immediately after neuraxial blockade or catheter removal.

- SOAP: Wait at least 1 hour after neuraxial placement and at least 1 hour after catheter removal before starting or resuming, whichever is greater

- The recommendations vary by society. The American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA) guidelines consider both pregnant and nonpregnant individuals, while the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) consensus statement is written specifically for pregnant patients.

- Indwelling catheters can be kept on low-dose UFH.

- Catheter removal should be at least 4-6 hours after the last dose. The next UFH dose should be at least 1 hour after catheter removal.

- The addition of NSAIDs in those with an epidural catheter and on thromboprophylaxis may increase the risk of bleeding complications.

- It can be beneficial to bridge with low-dose UFH due to shorter duration and because it can be resumed sooner in the following scenarios:

- Patients who need to receive thromboprophylaxis less than 12 hours after cesarean delivery

- Patients at risk of postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean delivery

- If there is a plan for a postpartum procedure (tubal ligation, epidural blood patch)

- If there is an indwelling catheter that needs to be removed

- It can be beneficial to bridge with low-dose UFH due to shorter duration and because it can be resumed sooner in the following scenarios:

- Intravenous UFH:

- Wait for at least 1 hour after neuraxial placement and at least 1 hour after catheter removal before starting or resuming, whichever is greater

General Management

- Pneumatic compression devices should be used until the patient is ambulatory and anticoagulation is resumed.6

- Warfarin, LMWH, and UFH do not accumulate in breast milk or cause anticoagulation in infants and, therefore, can be used in breastfeeding patients.6

References

- Leffert L, Butwick A, Carvalho B, et al. The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology consensus statement on the anesthetic management of pregnant and postpartum women receiving thromboprophylaxis or higher dose anticoagulants. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(3):928-44. PubMed

- Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1066-1074. PubMed

- DʼAlton ME, Friedman AM, Smiley RM, et al. National partnership for maternal safety: Consensus bundle on venous thromboembolism [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(6):1288. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):688-98. PubMed

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Women's Health Care Physicians. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 138: Inherited thrombophilias in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(3):706-717. PubMed

- Kolettis D, Craigo S. Thromboprophylaxis in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45(2):389-402. PubMed

- Practice bulletin No. 123: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(3):718-729. PubMed

- Brancazio LR, Roperti KA, Stierer R, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of subcutaneous heparin during the early third trimester of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(4):1240-45. PubMed

- Leffert LR, Dubois HM, Butwick AJ, et al. Neuraxial anesthesia in obstetric patients receiving thromboprophylaxis with unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin: A systematic review of spinal epidural hematoma. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(1):223-31. PubMed

- Horlocker TT, Vandermeuelen E, Kopp SL, et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine evidence-based guidelines (Fourth Edition) [published correction appears in Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(5):566. PubMed

Other References

- OA-SOAP Fellows Webinar Series: Thromboprophylaxis in Pregnancy. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.