Copy link

Lumbosacral Radiculopathy

Last updated: 08/14/2024

Key Points

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy is one of the leading causes of low back pain.

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy often affects more than one underlying nerve root, causing pain in one or more lumbar or sacral dermatomes. It may or may not be accompanied by loss of sensation and/or motor function.

- If conservative management fails, patients may benefit from epidural steroid injections (ESI) or other interventional treatments.

Introduction

- Low back pain is the leading cause of worldwide disability, with lumbosacral radiculopathy accounting for over one-third of these cases.1

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy is characterized by radiating pain in one or more lumbar or sacral dermatomes. It may or may not be accompanied by other radicular symptoms or decreased sensory and/or motor function.2

- The most common cause of radicular pain is lumbar disk protrusion/herniation with resultant nerve root compression or spondylosis.2,3

- Spontaneous improvement of acute lumbosacral radiculopathy following disc herniation or lumbar spinal stenosis is very high. However, concerns arise when symptoms worsen or are severe at presentation.

- Severe symptoms warrant further imaging and/or emergent surgical intervention.

- Treatment often depends on the period of pain:

- acute is defined as up to one month (in view of the high percentage of people who spontaneously recover during this period);

- subacute between one and three months; and

- chronic pain beyond three months (in view of reduced recovery after this period).2

Diagnostics

History and Physical Examination

- The most common symptoms of lumbosacral radiculopathy are pain and paresthesia.

- A positive straight leg test is most useful for diagnosing L4 and S1 radiculopathies. An internal hamstring reflex has been shown to be useful for diagnosing L5 radiculopathy.

- The L2-L4 nerve roots largely innervate the anterior thigh muscles. An acute injury can present with radiating back pain to the anterior thigh, which can possibly radiate to the knee, lower leg, and foot. Loss of sensation is common in pain areas. Reduced patellar reflex can also be seen. Coughing, leg straightening, or sneezing can worsen pain.3

- L5 radiculopathy often presents with pain down the lateral leg into the foot. There may also be a reduction in strength of big toe extension (extensor hallucis longus).3

- S1 radiculopathy can cause radiation of sacral or buttock pain into the posterior aspect of the patient’s leg into the foot or the perineum. It may also cause weakness of plantar flexion and loss of sensation along the posterior leg and lateral aspect of the foot. The Achilles reflex (S1) may be lost or diminished.3

- Other examination findings may include the inability to rise from a seated position, a history of knee buckling, toe-drag on ambulation, and diminished L4 and L5 deep tendon reflexes.

- Patients may also present with a positive Romberg test with a wide-based gait.

- Muscle strength is often only affected in severe cases due to multiple nerve roots supplying muscles.

- “Red flag” signs and symptoms include high fever (>38°C), saddle anesthesia, weakness in lower limbs, bladder or bowel dysfunction, gait disturbance, unexplained weight loss, etc.

- Other red flags in a patient’s history include a history of neoplasms, physical traumas, advanced age, immunodeficiency, intravenous drug use, corticosteroid use, or other immunosuppressive drug use.

Imaging

- Patients who do not respond to conservative therapy often need a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for further evaluation and to determine nerve root involvement.

- Imaging is not always a helpful diagnostic modality as almost 27% of patients without back pain have been found to have disc herniation on MRI.

- Computed tomography (CT) and myelography (CT with intrathecal administration of contrast) can be used in place of MRI when there is either a contraindication for an MRI, such as having a pacemaker device or defibrillator or when a standard CT or MRI is negative or equivocal.

- Patients with surgical spinal hardware are recommended to have a CT myelography for radiculopathy work-up.3

- Urgent imaging is recommended for cases of severe acute radiculopathy: worsening neurological deficits, suspected underlying neoplasm, epidural abscess, or cauda equina syndrome.2,3

Figure 1. Sagittal MRI showing a caudally oriented L4-L5 disc herniation. Source: Case courtesy of Báling Botz, Radiopaedia.org, rID; 87940. Link

Electromyography (EMG)

- EMG has a sensitivity between 50–80% for detecting radiculopathy.

- When imaging is either equivocal or negative with high suspicion for radiculopathy, nerve conduction studies may be warranted.

- EMG is accurate only after three weeks of persistent symptoms because it depends on fibrillation potentials after an acute injury.3

- EMG can be useful in differentiating lumbar radicular syndrome from peripheral neuropathy, as well as distinguishing neurogenic weakness from decreased muscular effort or muscle inhibition due to pain.2,3

- A marker for chronic L5 radiculopathy is atrophy of the extensor digitorum brevis and tibialis anterior demonstrated on EMG.3

Management

Conservative Management

- Recommended as first-line treatment for most patients

- Includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and activity modification

- Patients with subacute or chronic pain for whom NSAIDs or acetaminophen therapy is ineffective or insufficient, a trial of a nonbenzodiazepine skeletal muscle relaxant (e.g. cyclobenzaprine or tizanidine) can be considered as adjunctive therapy for up to four weeks.4

- If longer-term therapy is needed, duloxetine or other serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) may be used.5

- Additionally, it is important to discuss weight loss in obese patients.

- Opioids are only indicated for patients with persistent radiculopathy and severe pain.

- Due to the potential for harm and limited evidence of efficacy, such therapy is reserved for selected patients who have persistent, disabling symptoms despite trials of all other therapies, including nonsurgical interventional options and specialist evaluation.6

- Currently, there are no guidelines pertaining specifically to the management of chronic back pain with opioids. However, the American Pain Society recommends an initial course of opioids for chronic noncancer pain should be viewed as a short-term consisting of a therapeutic trial lasting from several weeks to several months. The decision to proceed with opioid therapy should be intentional and based on careful consideration of outcomes during the trial. Risks and benefits should be discussed with the patient.7

Interventional Therapies

- For patients with subacute or chronic radiculopathy or severe disabling chronic nonspecific low back pain, it is difficult to categorically advise when nonsurgical interventional therapies should be considered.

- For patients who have not responded to noninvasive therapies or those who are not interested in surgery or are not candidates for surgery, it is reasonable to consider nonsurgical interventional therapies.

ESI

- Considered for subacute lumbosacral radicular pain, i.e., if a patient has not improved after six weeks of conservative management

- In patients with chronic radicular complaints, epidural corticosteroids frequently do not provide any long-term improvement.2,3

- Commonly used injectable steroids include methylprednisolone acetate, triamcinolone acetate, betamethasone acetate, betamethasone phosphate, and dexamethasone phosphate.

- Animal studies have shown that intravascular injection into vertebral artery of particulate steroids causes neurological injury, whereas nonparticulate steroids such as dexamethasone and betamethasone phosphate do not. Nonparticulate steroids are becoming increasingly favored for the transforaminal approach.8

- One injection can provide up to three months of relief.

- The proposed mechanism of action of ESI is decreased inflammation via inhibition of phospholipase A2 and, therefore, the cyclooxygenase pathway, resulting in decreased prostaglandins.

- An additional mechanism of action includes suppression of ectopic discharges from injured nerve fibers.

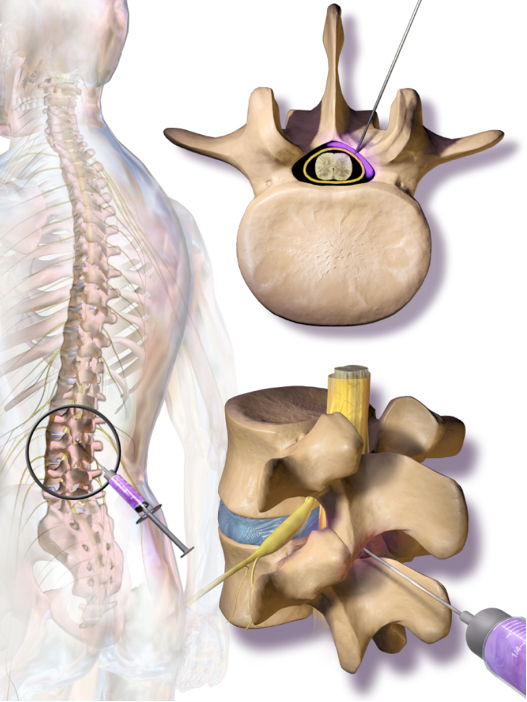

- There are three common approaches for epidural corticosteroid administration, depending on the needle’s path.2

- Transforaminal corticosteroid administration: The lateral foraminal space between 2 vertebrae is identified via an oblique view on a fluoroscopic X-ray, displaying the classic “Scottie dog” landmark.

- This allows for more precise medication distribution at the level of the inflamed nerve root. Transforaminal and parasagittal interlaminar ESI provide better outcomes than interlaminar injections. However, in practice, due to rare but potentially catastrophic neurological complications associated with the transforaminal approach, the interlaminar and caudal approaches should be considered, particularly in individuals with bilateral symptoms.

- Caudal corticosteroid administration: The sacral hiatus is identified via an AP view on fluoroscopic x-ray, where the epidural spinal needle is then inserted. Needle placement below the S2-S3 intervertebral disc space decreases the risk of dural puncture.8

- Interlaminar corticosteroid administration: Either a median or paramedian approach can be used. The needle penetrates the skin, subcutaneous tissue, supraspinous ligament (median approach) or paraspinal muscles (paramedian approach), and the ligamentum flavum.

- Transforaminal corticosteroid administration: The lateral foraminal space between 2 vertebrae is identified via an oblique view on a fluoroscopic X-ray, displaying the classic “Scottie dog” landmark.

- Absolute contraindications for ESI include systemic infection or local infection at the site of injection, bleeding diathesis or full anticoagulation, significant allergic reaction/hypersensitivity to contrast, anesthetic, or steroid, local malignancy, etc.8

- Complications following ESI are rare but may include bleeding, infection, allergic reaction, nerve injury, transient extremity numbness and tingling, postinjection pain, dural puncture causing positional headache, epidural abscess, epidural hematoma, side effects of steroids (flushing, weight gain, elevated blood glucose, mood changes, adrenal suppression).

Figure 2. Interlaminar epidural steroid injection at the lumbar level. Source: Medical Gallery of Blausen Medical. 2014. Wikipedia. Link

Pulsed Radiofrequency (PRF)

- In chronic lumbosacral radicular pain, PRF treatment adjacent to the spinal ganglion (DRG) is recommended.2

- In a systematic review and meta-analysis, four of six randomized control trials found PRF treatment resulted in greater reductions in pain scores after 12 weeks compared to the control groups.9 PRF is therefore recommended in patients with chronic radicular pain, defined as pain lasting for more than three months.10

- Reports of complications with PRF are rare.

Epidural Adhesiolysis/Epiduroscopy

- This intervention aims to mechanically dissolve epidural scar tissues to alleviate radicular pain and facilitate the spread of analgesic substances to possible areas of pain generation.2

- Epiduroscopy, which involves using video imaging of the epidural space, allows visualization of adhesions/lesions, enabling target adhesiolysis.

- Possible mechanisms of action include washing out inflammatory cytokines, increasing perfusion to ischemic nerve roots, mechanically disrupting scar tissue that may be contributing to pain, and enhancing the flow of steroids and local anesthetic to the pain-generating area.11

- There is currently no consensus on the method, solution to be used, or the duration of administration for epidural adhesiolysis.

Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS)

- Also referred to as dorsal column stimulation (DCS).

- DCS is reserved for patients with intractable back pain.

- This involves introducing electrodes into the epidural space—either percutaneously or through laminectomy—to modulate neural function and reduce pain by stimulating the dorsal aspect of the spinal cord.

- Complications associated with SCS are not rare.

Dorsal Root Ganglion (DRG) Stimulation

- DRG has emerged as a promising anatomical target for neuromodulation due to its unique characteristics, including somatotopic organization.

- It may provide added value compared to SCS for focal neuropathic pain syndromes, including lumbosacral radicular pain.

Surgical Intervention

- Because the most common cause is disc herniation, surgical intervention for lumbosacral radiculopathy often includes open discectomy or microdiscectomy.

- Indications for lumbar discectomy are widely debated. However, for patients with an acute and significant neurological loss of motor function due to a herniated disc, immediate surgical treatment is usually recommended.12

- Otherwise, an ideal operative candidate is one who has failed at least 8 weeks of nonoperative management without improvement and has a clinical examination that correlates with radiologic findings.

References

- Engle AM, Chen Y, Marascalchi B, et al. Lumbosacral radiculopathy: Inciting events and their association with epidural steroid injection outcomes. Pain Medicine. 2019; 20 (12): 2360–70. PubMed

- Peene L, Cohen SP, Kallewaard JW, et al. Lumbosacral radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2024; Volume 24 (3):525-52. PubMed

- Dydyk AM, Khan MZ, Singh P. Radicular back pain. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024. Link

- Van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, et al. Muscle relaxants for nonspecific low back pain: A systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane collaboration. Spine. 2003; 28(17):1978-92. PubMed

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017; 166 (7):514-530. PubMed

- Tucker HR, Scaff K, McCloud T, et al. Harms and benefits of opioids for management of non-surgical acute and chronic low back pain: A systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020; 54(11):664. Link

- Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009; 10(2):113-30. PubMed

- Patel K, Chopra P, Martinez S, et al. Epidural steroid injections. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024. Link

- Marliana A, Setyopranoto I, Setyaningsih I, et al. The effect of pulsed radiofrequency on radicular pain in lumbal herniated nucleus pulposus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Pain Med. 2021; 11 (2): e111420. PubMed

- Bicket MC, Hurley RW, Moon JY, et al. The development and validation of a quality assessment and rating of technique for injections of the spine (AQUARIUS). Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016; 41:80–85. PubMed

- Lee F, Jamison DE, Hurley RW, et al. Epidural lysis of adhesions. Korean J Pain. 2014; 27: 3–15. PubMed

- Bruggeman AJ, Decker RC. Surgical treatment and outcomes of lumbar radiculopathy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2011; 22 (1):161-177. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.