Copy link

Living Donor Liver Transplantation

Last updated: 06/20/2024

Key Points

- Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) recipients have improved outcomes when compared to deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT) recipients.

- Living donors undertake surgical risk with no benefit to themselves. Therefore, the optimal anesthetic technique should be employed.

- A donor graft that is too small can result in a small-for-size syndrome (SFSS) in the recipient, which is associated with poor outcomes.

- Adequate liver mass must be left in the donor to allow for successful regeneration and the return of normal hepatic function.

- Donors have a low mortality rate, with most surgical complications being self-limiting.

- Donors typically return to their baseline function within 6 months and have almost complete regeneration of their liver within a year.

Introduction

- Living donors are often family members, friends, or acquaintances otherwise known to the recipient. Occasionally, anonymous donors offer up a graft for wholly altruistic purposes. The number of this type of donor has grown in recent years.1

- Donors undertake all the risks of anesthesia and surgery to provide a lifesaving graft to a recipient with no real benefit to themselves. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to ensure that every step is taken to guarantee donor safety while seeking the best possible outcome for the recipient.

- The selection process in the United States mandates the use of an independent living donor advocate (ILDA), whose sole responsibility is to advocate for the donor. This individual must provide unbiased information to the donor, as most other involved parties have some form of relationship with the recipient.2

- The process of evaluating a donor organ is rigorous and involves extensive, time-consuming, and expensive outpatient investigations.

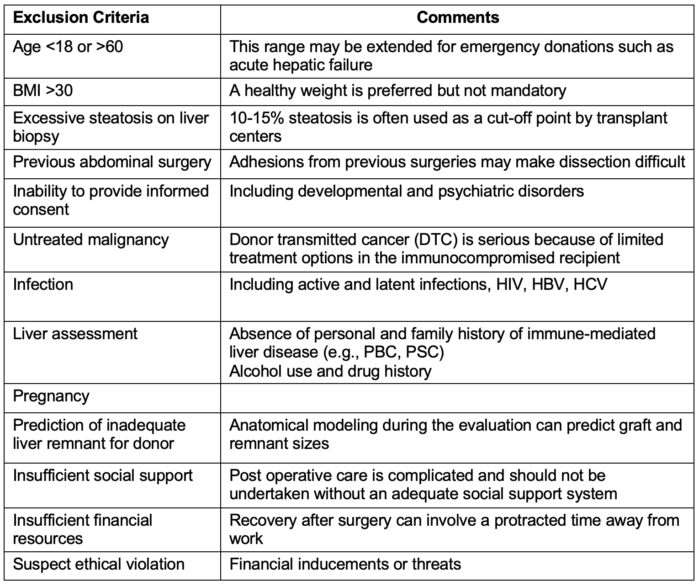

- There are few absolute and many relative exclusion criteria which must be considered before accepting a graft from a living donor. These include demographic, health history, and age ethical considerations.2 Donors with untreated health conditions and who lack financial and support resources are also excluded (Table 1).1

- LDLT recipients do well when compared to DDLT. This is due to earlier transplantation in the recipient’s disease progression, better health at the time of transplant, better donor graft quality, and an opportunity for any medical optimization prior to transplant due to the elective nature of the case.2

Table 1. Examples of exclusion criteria for potential donors undergoing evaluation for living donor liver transplantation. Criteria are often transplant-center-specific and may vary depending on the urgency of the case. Abbreviations: PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Surgical Considerations

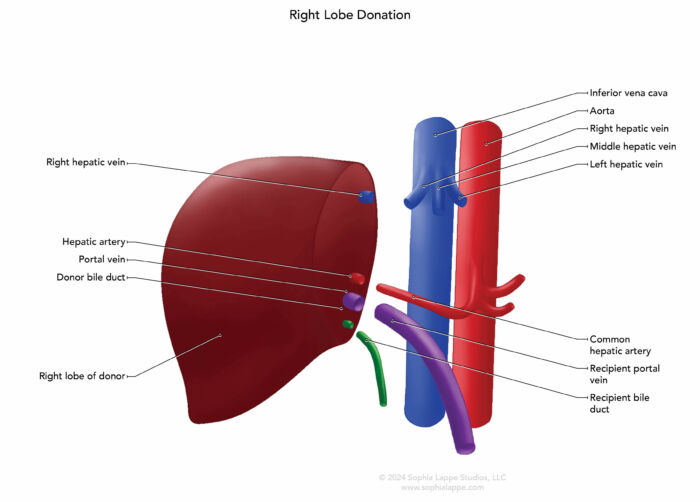

- A majority of LDLT patients receive the right lobe from a live donor due to the left lobe being inadequate for an average-sized adult, whereas in DDLT, the recipients usually receive a whole donor organ graft.2

- Graft selection is based on preoperative screening, including computed tomography imaging, which determines the appropriate graft size that will be compatible with the recipient’s portal blood flow.

- Too high a portal blood flow for a small graft leads to SFSS, which is associated with poorer outcomes.3

- The aim is to ensure that around 30% of liver volume remains for the donor to have adequate liver function and regeneration and a graft-to-recipient weight ratio (GRWR) of more than 0.8% to ensure enough liver mass for the recipient’s needs.

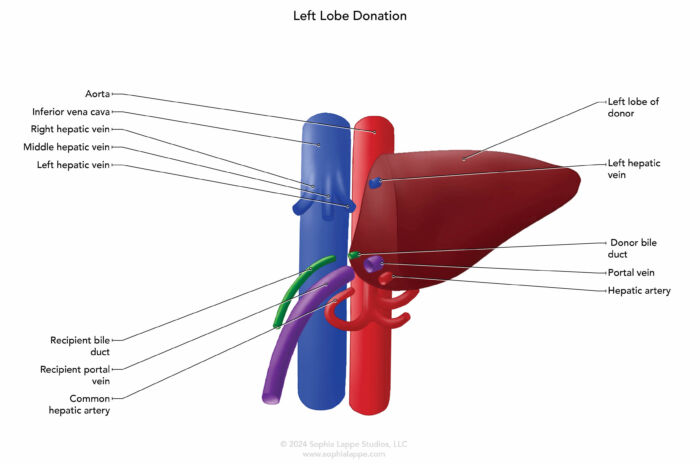

- Prior to reperfusion in LDLT, the hepatic vein anastomosis may require cadaveric vein grafts to ensure good flow out of the liver to minimize the chance of hepatic congestion. The remaining anastomoses are performed in a similar manner to DDLT (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Common surgical approaches for left (A) and right (B) liver lobe donation showing vascular and biliary anastomoses.

- After reperfusion, if the graft size is assessed as being too small (GRWR less than 0.8%), there are methods to help overcome the high shear pressures due to high portal blood flow. These include ligating the splenic artery to increase blood flow via the hepatic artery, which in turn reduces portal blood flow through the hepatic artery buffer response (HABR). Alternative techniques include portosystemic shunts and/or pharmacologic therapies to decrease splanchnic blood flow.4

- Coordination between the donor and recipient surgical teams can be challenging. The aim is to prepare the recipient for reception of the donor graft with minimal delay for either team. The recipient team does not want protracted hemodynamic instability while waiting for the donor graft, and the donor graft should not experience protracted cold ischemia time waiting for the recipient team to finish its preparation to receive the graft.

Anesthetic Considerations: Donor

- The anesthetic for the donor can be a volatile or total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA)-based technique. Multimodal analgesics such as gabapentinoids, dexmedetomidine, ketamine, intravenous opioids, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are frequently employed. Epidural anesthesia is not often utilized due to the potential for postoperative coagulopathy.5 However, this choice is transplant center specific. There are other truncal blocks available, such as transversus abdominus plane, erector spinae, or rectus sheath blocks.

- The placement of Invasive lines, such as arterial or central lines, is not mandatory, and the decision should be based on good communication with the surgical team.

- The donor is usually extubated at the end of the surgery and more often transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for close monitoring in the immediate postoperative period.

Anesthetic Considerations: Recipient

- LDLT is performed in the same three phases as DDLT: the dissection and hepatectomy phase, the anhepatic phase, and the post-reperfusion phase. Each phase has its own set of challenges.

- Please see the OA summary on Adult Liver Transplantation: Anesthesia Considerations. Link

Outcomes for Donors

- Most liver regeneration occurs within the first 2 weeks after surgery, up to 80% by 3 months, and almost complete regeneration by 1 year.

- Laboratory blood test abnormalities typically normalize within 3 months. However, thrombocytopenia may take longer to return to baseline levels.

- The donor mortality rate is less than 0.5%, and the surgical complication rate is around 24%. However, complications are usually short-lived and minimally debilitating, with most donors recovering to their baseline function and general health by 6 months after the operation.

- A study which compared donors with potential donors (who were excluded due to ABO mismatch) and looked at both groups’ long-term health-related quality of life (HRQoL) found no significant difference between donors and potential donors.6 However, donors with recipients who survived had a higher HRQoL in comparison to those who did not survive.

- A large majority of donors are satisfied with the donation process and would elect to do so again.7

Outcomes for Recipients

- The recipient will often have a longer intensive care unit (ICU) stay because of the need for a higher level of monitoring due to the increased difficulty of surgery.

- LDLT recipients have both a higher graft survival rate at 5 years compared to DDLT recipients and a better 5-year survival rate.8

References

- Cattral M, Selzer N. Anonymous living donor liver transplantation: the altruistic strangers. Gastroenterol. 2023;165(6): 1315-7. PubMed

- Hendrickse A, Ko J, Sakai T. The care of donors and recipients in adult living donor liver transplantation. BJA Educ. 2022;22(10): 387-95. PubMed

- Yagi S, Uemoto S. Small-for-size syndrome in living donor liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat.Dis Int. 2012;11(6): 570-6. PubMed

- Troisi R, Berardi G, Tomassini F, et al. Graft inflow modulation in adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: a systematic review. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2017;31: 127-35. PubMed

- Koul A, Pant D, Rudravaram S, et al. Thoracic epidural analgesia in donor hepatectomy: an analysis. Liver Transpl. 2018;24: 214-21. PubMed

- Abdel-Khalek EE, Abdel-Wahib M, Elgazzar M, et al. Long-term follow up of living liver donors: a single center experience. Liver Transpl. 2022; 28(9): 1490-9. PubMed

- Butt Z, Dew M, Liu Q, et al. Psychological outcomes of living liver donors from a multicenter prospective study: results from the Adult-to Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study 2 (A2ALL-2). Am J Transplant. 2015;17: 1267-77. PubMed

- Kwong A, Kim W, Lake J., et al. OPTN/SRTR 2022 Annual Data Report: Liver. HHS/HRSA; 2024. Accessed April 7th, 2024. Link

Other References

- Cotler LJ, Lemon K. Living donor liver transplantation in adults. In Post E (Ed). UpToDate. Accessed April 7th, 2024. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.