Copy link

Klippel Feil Syndrome

Last updated: 01/12/2023

Key Points

- Klippel Feil Syndrome (KFS) is a rare congenital disorder characterized by the fusion of the cervical vertebrae.

- Difficult intubation should be anticipated due to severely limited flexion and extension of the cervical spine and possible cervical spine instability.

- The number of direct laryngoscopy attempts in patients with KFS should be limited and alternative intubation techniques should be attempted early.

Introduction

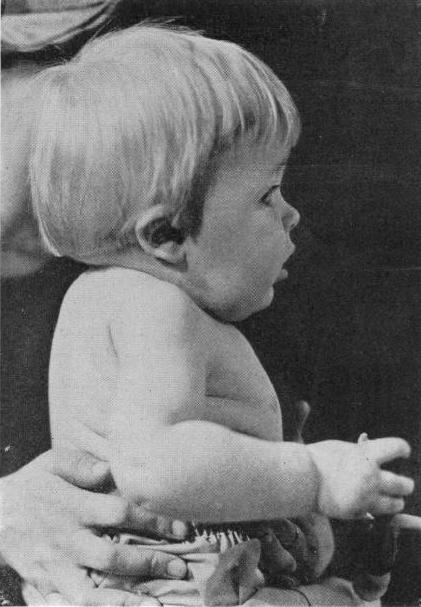

- KFS was described by Maurice Klippel and Andre Feil in 1912 with the classic triad of:1,2

- short neck;

- severely decreased cervical range of motion; and

- low posterior hairline.

- The defining feature is the congenital fusion of two or more cervical vertebrae.1

- KFS is a result of incomplete segmentation during early fetal development.

- Recognition may be difficult as less than 50% of patients have all three features.

- The severity of symptoms may vary considerably.

Figure 1. Child with Klippel-Feil Syndrome. Noble TP, Frawley JM. The Klippel-Feil syndrome: numerical reduction of cervical vertebrae. Ann Surg. 1925;82(5):728-734. (Wikimedia Commons)

- The incidence of KPS is approximately 1 in 42,000 births.2

- Most cases are sporadic.

- Autosomal dominant (GDF6 and GDF3 gene mutations) and recessive inheritance (MEOX1 mutation) patterns have been described.2

- KPS may be present as part of hemifacial microsomia or Wildervanck (Cervico-oculo-acoustic) syndrome.

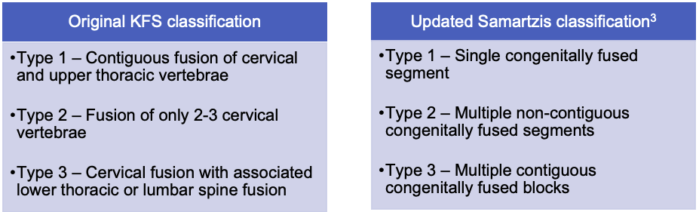

Table 1. The original classification of KFS described in 1919 by Andre Feil was based on fusion patterns in cervical, thoracic, and lumber spine. The updated classification by Samartzis in 2006 is based on fusion patterns, specifically of the cervical vertebrae.

Figure 2. Anterior-posterior and lateral neck x-rays showing fused C2, C3, and C4 vertebrae. Case courtesy of Mohammad A. ElBeialy, Radiopaedia.org, rID:23924.

Associated Anomalies1,4

- Atlanto-occipital fusion

- Chiari malformation

- Hearing impairment, sensorineural hearing loss

- Ocular anomalies – strabismus, nystagmus, or colobomas

- Cleft lip and/or palate

- Spinal canal stenosis

- Scoliosis

- Torticollis

- Sprengel deformity – congenital elevated scapula and resulting weakness of the arm

- Rib abnormalities

- Cardiac anomalies – most commonly ventricular septal defects

- Urogenital anomalies – renal hypoplasia or agenesis, or hydronephrosis

- Neural tube defects

Clinical Presentation

- There is wide variability in the clinical presentation depending on the type and degree of severity.1

- Limited range of motion of the neck is the most common finding.

- Patients who do present as children may have more extensive fusion.

- Patients may have increased susceptibility to cervical degenerative changes, spinal cord injury from minor trauma, and neurological changes with increasing age.

- Neurological changes include radiculopathy, myelopathy, paraplegia, hemiplegia, cranial nerve palsy or cervical nerve palsy.

- Patients may present for cervical or craniocervical fusion to stabilize the spine or decompressive laminectomy for spinal stenosis.

Figure 3. Adult with KFS demonstrating short, webbed neck. Reproduced with permission from Khawaja OM, et al. Crisis resource management of the airway in a patient with Klippel-Feil syndrome, congenital deafness, and aortic dissection. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(4):1220-25.

Evaluation

- A multidisciplinary consultation with otolaryngology, craniofacial/plastics, and neurosurgical or orthopedic spine team should be considered to guide evaluation.

- History

- Airway obstruction

- Neurologic symptoms

- Prior surgeries, anesthetics, and intubations

- Developmental stage, coping skills, cooperation (if considering awake intubation)

- Physical exam

- Carefully perform airway evaluation

- Establish neurologic baseline

- Evaluate for cardiac murmurs

- Imaging

- Anteroposterior and lateral cervical spine radiographs in neutral, flexion and extension evaluate fused segments and cervical spine instability.4

- CT may demonstrate canal stenosis.

- MRI indicated if neurological deficits are present on exam.

- Echocardiogram may be considered to rule out congenital cardiac disease.

- Renal ultrasound can screen for genitourinary abnormalities.

Anesthetic Considerations and Management

- Difficulty of airway management is thought to increase as neck mobility decreases with age.

Preoperative Set-Up

- Patients may be difficult mask ventilation due to multilevel upper airway obstruction.

- Nasopharyngeal airways (NPA), oropharyngeal airways (OPA)

- Supraglottic airways (SGA)

- Two experienced providers for bag-mask ventilation

- Difficult direct laryngoscopic view should be anticipated.

- Fiberoptic bronchoscope

- Videolaryngoscope

- SGA designed to facilitate tracheal intubation (“intubating laryngeal mask airway”)

- Cannot-intubate, cannot-ventilate scenario should be anticipated.1

- ENT surgeons should be consulted as appropriate.

- Availability of emergency tracheostomy kit should be confirmed.

- Availability of sugammadex if rocuronium or vecuronium is used for paralysis should be ensured.

Induction/Airway Management

- If the patient is developmentally appropriate and cooperative, consider an awake fiberoptic intubation. If not, an intravenous (IV) or mask induction with the maintenance of spontaneous ventilation may be the safest alternative.1,5

- Preinduction peripheral IV-line placement should be considered.

- Awake placement of NPA can be a helpful adjunct.

- Spontaneous ventilation should be maintained until the ability to mask ventilate is confirmed.

- SGA should be used if mask ventilation is difficult.

- If direct laryngoscopy is attempted for intubation, it should be done by the most experienced laryngoscopist, and it should be limited to one or two attempts.

- Using alternative intubation methods should be considered early, such as flexible bronchoscopic intubation (FBI), video laryngoscopy, or FBI through an SGA. Fiberoptic intubation is the preferred method of airway management as manipulation of the neck, including flexion or extension under anesthesia, could cause neurologic injury.1

- Supplemental oxygen should be used during intubation attempts.

Special Considerations

- Manual inline stabilization should be maintained in KFS patients with unstable necks.1

- Neurophysiologic monitoring with somatosensory evoked potentials and motor evoked potentials should be considered in KFS patients undergoing spinal surgery or at risk for spinal cord compression during longer surgeries or those requiring neck movement.

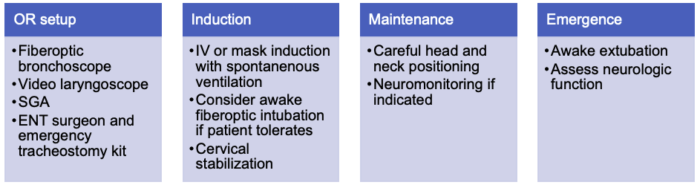

Table 2. Summary of anesthesia setup and management for patients with KFS.

References

- Holzman RS, Nargozian CD. The head and neck: specialty and multidisciplinary surgery. In: Holzman RS, Mancuso TJ, Polaner DM, Gravlee, GP. A Practical Approach to Pediatric Anesthesia. Second edition. LWW; 2015.

- Khan JA. Klippel-Feil syndrome. Orphan Anesthesia A&I Online. 2016;57 Supp. 11. Link

- Samartzis DD, Herman J, Lubicky JP, et al. Classification of congenitally fused cervical patterns in Klippel-Feil patients: epidemiology and role in the development of cervical spine-related symptoms. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(21): E798-804. PubMed

- Oliveira CRD. Pediatric syndromes with noncraniofacial anomalies impacting the airways. Paediatr Anaesth. 2020;30(3):304-10. PubMed

- Khawaja OM, Reed JT, Shaefi S, et al. Crisis resource management of the airway in a patient with Klippel-Feil syndrome, congenital deafness, and aortic dissection. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(4):1220-25. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.