Copy link

Interstitial Lung Disease: Preoperative Evaluation and Anesthesia Considerations

Last updated: 04/01/2025

Key Points

- Patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) are at an increased risk for postoperative pulmonary complications (PPC), with the highest mortality rates.

- Preoperative evaluation and pulmonary risk stratification include a validated tool such as the ARISCAT, consideration of all ILD-related factors, and medical optimization of pulmonary and nonpulmonary conditions.

- Intraoperative considerations for patients with ILD include lung protective ventilation, euvolemic fluid management, regional anesthesia if feasible, and early extubation to noninvasive ventilation.

Introduction

- ILD is a large group of diseases with the endpoint of fibrotic and inflammatory destruction of the lung parenchyma.1 ILDs are divided based on etiology into:

- Identifiable: occupational, autoimmune, and environmental

- Idiopathic: such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF); IPF is the most common severe etiology (~50-60%) of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.1

- Patients with ILD are at an increased risk for PPCs, such as acute exacerbation of lung disease, acute lung injury, respiratory failure, pneumonia, atelectasis, and pneumothorax.

- Acute exacerbation of ILD may result in higher mortality rates (~ 40-60%), mainly in patients who experience acute exacerbation or those who undergo emergency surgery.2

- Possible explanations for increased risk include:

- Ventilator-induced lung injury accelerates the fibroproliferative process.

- Atelectotrauma, barotrauma, or hyperoxia causes further lung damage.

- Microaspiration, increased closed lung volume, right ventricular dysfunction, negative pressure pulmonary edema, and increased fibrocytes.2

Epidemiology

- The incidence of IPF as the most common idiopathic ILD is 5.6/100,000 person-years.

- Median survival is 2-3 years after diagnosis, and IPF is the diagnosis associated with the worst prognosis and mortality.1

- It presents as progressive interstitial pneumonitis in older adults and a histological and radiological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonitis.

- The 5-year survival rates for different types of ILD are 91.6% for sarcoidosis, 69.7% for connective tissue disease-related ILD, and 35% for IPF.

Evaluation of ILD

Clinical diagnosis is based on the combined clinical picture, imaging, and biopsy results.

- Clinical presentation includes chronic dry cough, progressive dyspnea, and bibasilar crackles on auscultation.

- Diagnostic modalities: chest radiography, pulmonary function tests (PFT) with a restrictive pattern, and high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) chest.

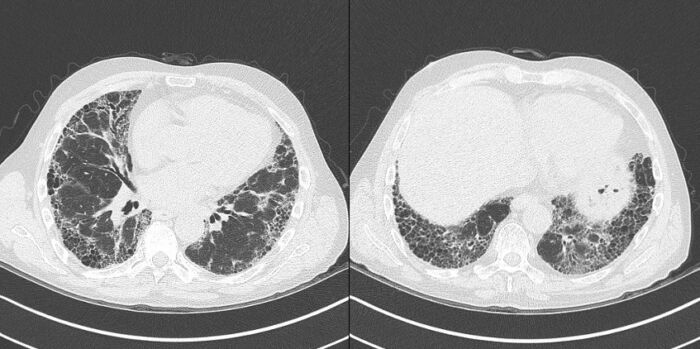

- Usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP) pattern on imaging represents accelerated disease progression and a worse prognosis (Figures 1 & 2a, 2b).

- Dense fibrosis with scarring and a honeycomb appearance is common.

- Subpleural and paraseptal fibrosis can be present.

- Evidence of severe disease includes:

- A decline in forced vital capacity (FVC) on PFT strongly correlates with decreased survival.

- One year risk of death is twofold higher when there is a 6-month decline of FVC by 5-10%.

- A lower 6-minute walk test is associated with increased hospitalization and mortality risk.

- Visually identified disease progression on an HRCT scan has been identified as an independent predictor of mortality.1,3

Figure 1. Chest X-ray showing UIP pattern: Small volume lungs with bilateral increased interstitial markings, most pronounced peripherally, without a zonal predominance. Source: Case courtesy of Ian Bickle, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 26493. Link

Figure 2a, 2b. High-resolution CT chest showing extensive honeycombing in both lungs in a subpleural and basal distribution with consequential tractional bronchiectasis. Source: Case courtesy of Ian Bickle, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 26493. Link

Management of ILD

Management is mainly supportive.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation

- Supplemental oxygen

- Antifibrotic pharmaceutical agents such as pirfenidone and nintedanib.4,5

- Both have been shown to slow the progression of the disease and improve survival.

- Both showed a slower decline in FVC.

- Both are associated with a decreased risk of acute exacerbation of ILD.

- Referral for lung transplant continues to be the only intervention that can increase life expectancy in patients with end-stage ILD.

Preoperative Evaluation, Risk Stratification, and Optimization

- Preoperative evaluation of patients with ILD should focus on assessing the risk of PPCs and identifying opportunities to optimize the patient, including optimization of other comorbidities.

- Common PPCs that are associated with increased mortality in this population include acute exacerbation of ILD, acute respiratory failure, postoperative pneumonia, atelectasis, pleural effusion, pulmonary embolism, bronchospasm, and postoperative pneumothorax.

Risk Stratification

- Patients with ILD are at a higher risk for PPCs than those without ILD.

- Patients with ILD undergoing lung cancer resection or emergency surgery have a higher risk for PPCs than patients undergoing nonthoracic surgery or elective surgical lung biopsy for ILD diagnosis.

- Nonmodifiable risk factors for PPCs include:

- Male gender

- Increasing age

- Severe ILD

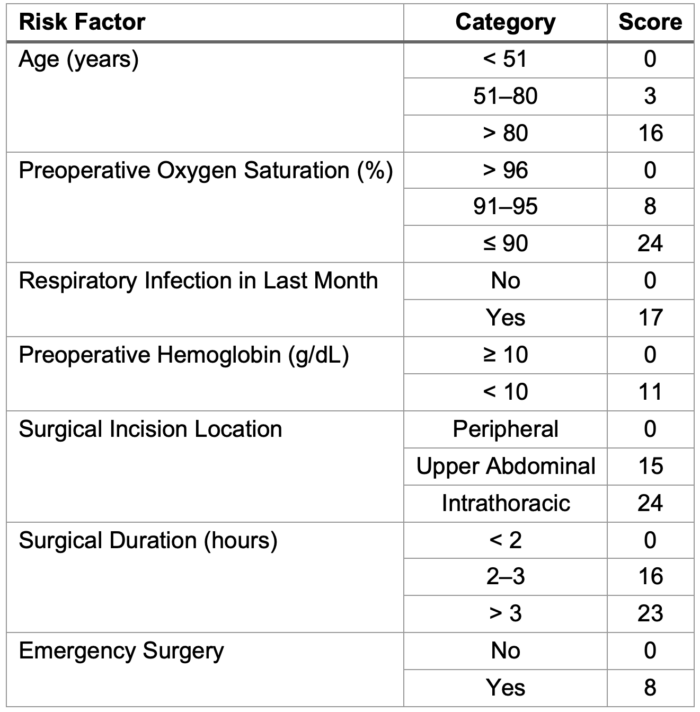

- Assess Respiratory Risk in Surgical Patients in Catalonia (ARISCAT) pulmonary risk calculator is a validated tool for predicting PPCs in the general population (Table 1).

Table 1. ARISCAT Pulmonary Risk Stratification Calculator6

- Risk stratification based on the total ARISCAT score:

- Low risk: 0–25 points (Risk of PPCs < 1.6%)

- Intermediate risk: 26–44 points (Risk of PPCs ~13.3%)

- High risk: ≥ 45 points (Risk of PPCs ~42.1%)

- In addition to ARSICAT, preoperative evaluation of ILD patients should include PFT, cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), and a 6-minute Walk Test (6MWT) to evaluate those with worsening disease and rapid progression.

- PFT: 6-12 month decrease in diffusion capacity (DLCO) by > 15%, FVC <80% on preoperative PFT is associated with increased cardiopulmonary complications and worse long-term survival after lung resection.

- CPET: VO2 max < 8.3 mL/kg/min

- 6MWT: 50-meter decline

- Identification of ILD patients at high risk of acute exacerbation of ILD in the postoperative setting. The following risk factors are predictors of acute exacerbation:

- Surgical lung resection is more than a wedge resection.

- FVC < 80% predicted

- HRCT shows the usual interstitial pneumonitis pattern.

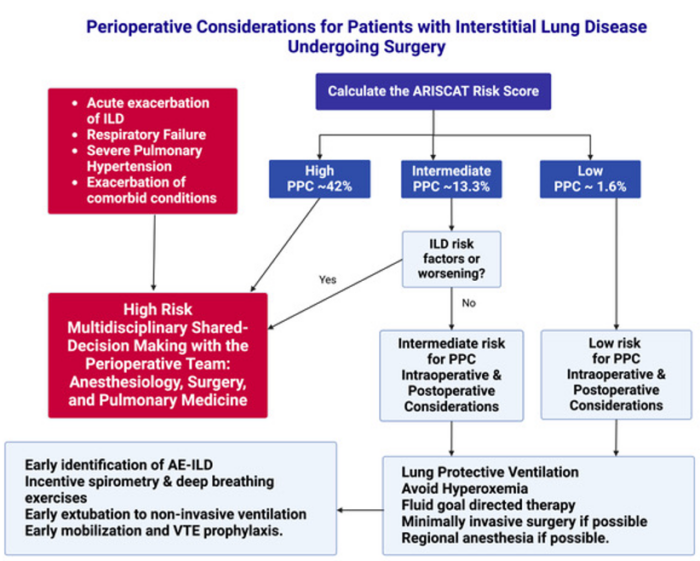

- Patients considered high-risk should have a shared decision-making discussion regarding the risks and benefits of proceeding with the planned procedure versus alternatives to surgery (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Summary of the Perioperative Considerations for Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease Undergoing Surgery. Created in BioRender. Mohamed, B. (2025) Abbreviations: ILD, interstitial lung disease; PPC, postoperative pulmonary complications; AE-ILD, acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease, VTE; venous thromboembolism.

Preoperative Evaluation and Optimization of Comorbidities

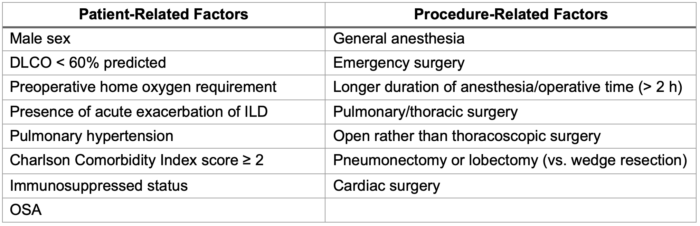

- Survival of ILD can be impacted by the associated comorbid conditions such as coronary artery disease, cardiovascular disorders, and lung cancer (Table 2).

- The ultimate goal of preoperative evaluation is to:

- Identify patients at high risk

- Evaluate modifiable risk factors

- Optimize comorbidities

- Recommended preoperative testing includes:

- Spirometry

- DLCO

- 6 Minute Walk Test (6MWT)

- Assessment of the Charlson Comorbidity Index

- Transthoracic echocardiogram

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) screening

- Patients with IPF (the most common idiopathic ILD) have a higher prevalence of the following comorbid conditions.

- Cardiac comorbidities: coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, and atrial fibrillation

- Pulmonary comorbidities: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, and venous thromboembolism

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Defined as increased pulmonary vascular resistance of > 3 Wood units, mean pulmonary arterial pressure of >20 mmHg at rest, or mean pulmonary pressure of 25 mmHg or more by right heart catheter

- Present in 30-50% of advanced cases

- Pulmonary HTN in IPF patients is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

- Abnormal brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels have a strong association with a worse prognosis.

- Obstructive sleep apnea: Screening for OSA is highly recommended, as it is very common in patients with IPF and may contribute to PPCs.

- Smoking: Preoperative smoking cessation should be strongly recommended. Radiologic progression has been noticed in former smokers.

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is also highly prevalent in IPF patients. Poorly controlled GERD may contribute to disease progression and possibly increase the risk of acute exacerbation of ILD.

- Malnutrition: hypoalbuminemia and low serum prealbumin are indicators for protein-calorie malnutrition and are associated with poor prognosis.

- Chronic Kidney Disease: Associated with increased all-cause mortality.

- Associated with lower diffusion capacity

- Associated with lower 6MWT distance

Table 2. Patient- and Procedure-Related Risk Factors for ILD-Related PPCs

Intraoperative Anesthetic Considerations for Non-Thoracic Surgery

- Surgery-related risk factors associated with increased risk of postoperative pulmonary complications include

- Cardiac surgery

- Emergency surgery

- Lung resection

- Prolonged surgery time: an independent risk factor for postoperative acute respiratory worsening.

- Longer mechanical ventilation duration resulting in ventilator-associated lung injury.

Intraoperative Considerations

- Lung protective ventilation:

- Low tidal volume: 6-8 mL/kg of ideal body weight.

- PEEP to maintain adequate oxygenation

- Plateau pressure of < 30 cm H2O

- Avoid hyperoxemia

- Absorptive atelectasis

- Increased oxidative stress from exposure to high FiO2

- Lower FiO2 to maintain SaO2 88-92%

- Restrictive fluid management: avoid fluid overload and maintain euvolemia using goal-directed fluid therapy.

- Choose a minimally invasive approach to surgery, if possible.

- Regional anesthesia, when feasible, is preferred over general anesthesia in this population.

Postoperative Considerations

The focus is to prevent PPCs in this population, including:

- Acute exacerbation of ILD

- Pneumonia

- Prolonged pneumothorax

- Acute exacerbation of pulmonary hypertension

Acute Exacerbation of ILD

- Early identification is the key for early management and prevention of worsening respiratory status.

- Criteria for acute exacerbation of ILD (AE-ILD)

- Underlying diagnosis of ILD

- Acute worsening of respiratory symptoms within 30 days after surgery

- CT findings of new bilateral ground glass opacification and/or consolidation in addition to the baseline ILD pattern

- AE-ILD occurs in 9.3% of pulmonary resection, with a mortality rate of 25-43.9%.

- It is most likely to occur after lung resection but can also happen after nonthoracic surgery.

- The use of antibiotics and steroids is still being researched for their benefits in preventing AE-ILD. To date, continuing or initiating either treatment modality has no benefits.1

- Minimizing the risk of microaspiration in this population will prevent inflammatory response in patients with ILD.

- Treatment: Empiric antibiotics and high-dose corticosteroid therapy

Postoperative pneumonia: Treat using appropriate antibiotics when indicated (fever, sputum production, and opacification on chest imaging)

- Strategies to reduce the incidence of postoperative pulmonary complications:

- Incentive spirometry

- Oral care

- Induced coughing

- Deep breathing exercises

- Head of the bed elevation

- Early mobilization

- Regional or local anesthesia at the surgical site might help optimize respiratory mechanics and avoid splinting and atelectasis.

- There is no evidence to support the routine use of prophylactic antibiotics.

- Early extubation to noninvasive ventilation such as high flow nasal cannula or bilevel positive airway pressure

- Early mobilization and physical therapy to prevent atelectasis and venous thromboembolism (VTE)

- VTE prophylaxis using prophylactic anticoagulation

- Stress dose of steroids when indicated

References

- Carr ZJ, Yan L, Chavez-Duarte J, et al. Perioperative management of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis undergoing noncardiac surgery: A narrative review. Int J Gen Med. 2022; 15: 2087-2100. PubMed

- Patel NM, Kulkarni T, Dilling D, et al. Preoperative evaluation of patients with interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2019; 156(5):826-33. PubMed

- Best AC, Meng J, Lynch AM, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Physiologic test, quantitative CT indexes, and CT visual scores as predictors of mortality. Radiology. 2008; 246(3): 935-40. PubMed

- Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of pooled data from three multinational phase 3 trials. Eur Respir J. 2016; 47(1): 243-53. PubMed

- Richeldi L, Bois RM du, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370(22): 2017-82. PubMed

- Canet J, Gallart L, Gomar C, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in a population-based surgical cohort. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1338-50. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.