Copy link

Heparin Resistance

Last updated: 01/20/2025

Key Points

- Heparin resistance occurs when the anticoagulant response to heparin is inadequate, requiring higher doses to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation.

- Common causes include antithrombin (AT) deficiency (most common), increased heparin clearance, and elevated levels of heparin-binding proteins.

- Management strategies include AT supplementation, administration of fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and the use of alternative anticoagulants.

Definition

- Heparin resistance is defined as the failure to achieve a specific level of anticoagulation despite adequate doses of heparin, requiring higher than usual doses of heparin to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation.1

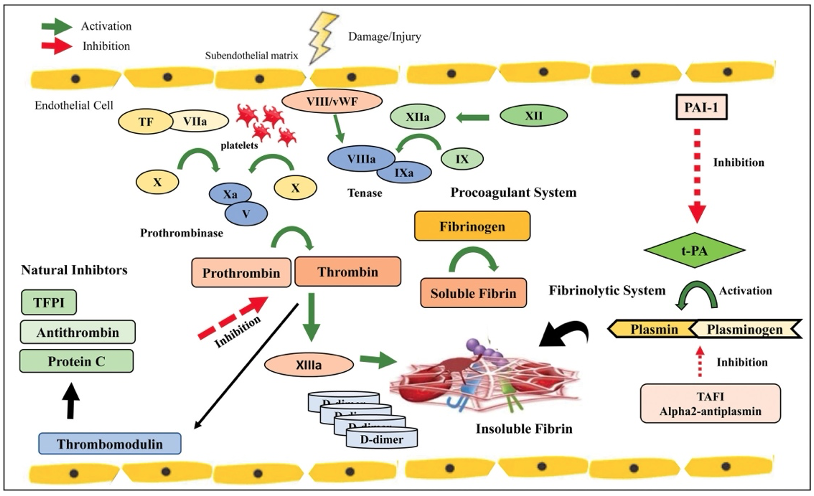

- Heparin binds to and potentiates the action of antithrombin (AT), formerly known as antithrombin III (AT III), which in turn inactivates factors XIIa, XIa, IXa, and IIa (thrombin), thereby achieving anticoagulation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Coagulation cascade. Note that antithrombin inhibits the formation of thrombin, leading to anticoagulation. Used with permission from Crochemore T. et al. Anesth Analg 2024.2

- Heparin resistance is typically defined in the context of unfractionated heparin.1

- In patients undergoing procedures requiring cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), heparin resistance is more specifically defined as the need for more than 500 units/kg of heparin to achieve an activated clotting time (ACT) of 400 to 480 seconds.3

Incidence and Mechanism

- The reported incidence of heparin resistance ranges between 4% and 26%, depending on the initial heparin bolus administered and the target ACT level required before initiating CPB.3,4

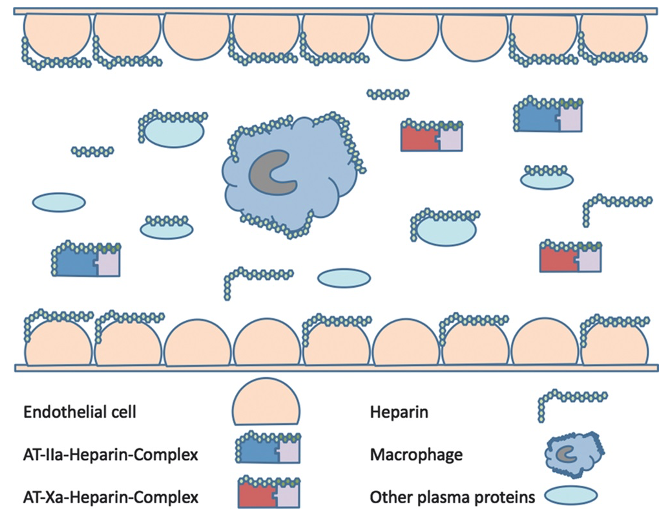

- Heparin resistance may be mediated via AT or protein binding, among other causes (Figure 2).1,4

Figure 2. Heparin binds to antithrombin (AT) to form a complex with factors IIa or Xa. Heparin also nonspecifically binds to AT, macrophages, and other plasma proteins. Heparin may also remain unbound in the plasma. Used with permission from Finley A et al. Anesth Analg 2013.4

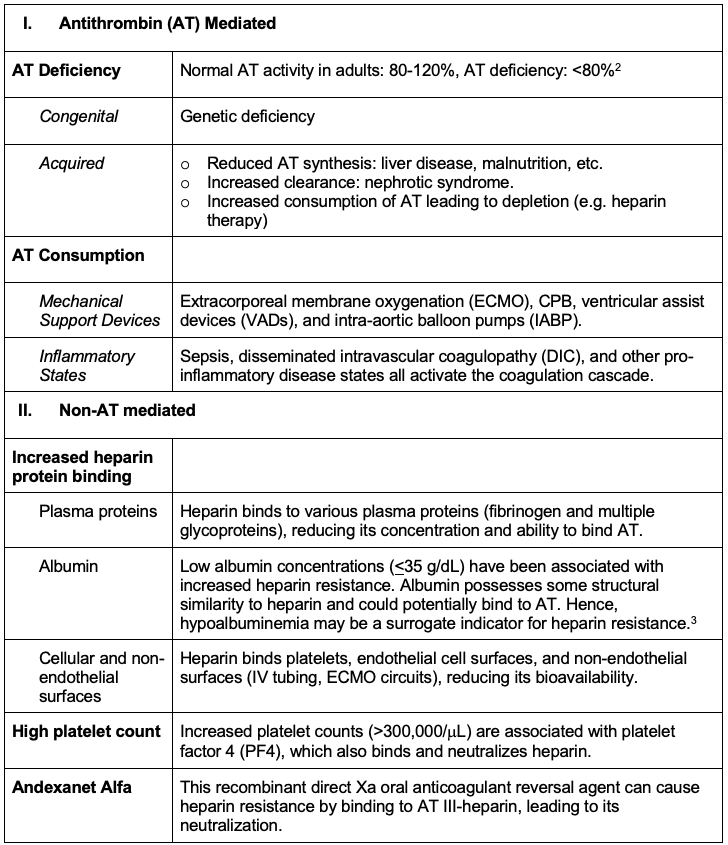

Mechanisms of Heparin Resistance1,3,4

Table 1. Mechanisms of heparin resistance

Diagnosis

- Heparin resistance should always be suspected when usual heparin doses fail to prolong the ACT (or activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT)) to the desired therapeutic range.1

- Laboratory tests:

- AT activity: levels can be measured using chromogenic assays.

- Heparin levels: heparin levels can be quantified directly.

- Heparin-binding proteins: elevated acute-phase reactants can indicate the presence of heparin-binding proteins.

- Criteria:

- Diagnosis generally involves clinical suspicion and laboratory confirmation.

- In the perioperative setting, ACT (or aPTT) response to heparin administration, heparin concentration, and AT levels are typically used to diagnose heparin resistance. If the laboratory capabilities and time permit, anti-factor Xa can also be used to measure the heparin level.1

Management

- Administration of additional heparin:

- This is a common first practice. If the ACT is low, additional heparin is typically dosed, up to 500 units/kg, as a first step. Higher doses may increase the risk of bleeding due to heparin rebound and the nonspecific binding of heparin to plasma proteins and dissociation over time.3

- Assess AT levels:

- Decreased AT levels help to identify deficiency as a contributor to heparin resistance, though results may not be available during the perioperative timeframe.3

- AT supplementation:

- AT administration is the treatment of choice for heparin resistance due to AT deficiency. AT use is highly recommended to reduce FFP transfusion with AT-mediated heparin resistance immediately before CPB (Class I, Level A evidence).3

- FFP can be used if AT concentrates aren’t available. However, much larger volumes may be required (more than 500-1000mL)3, increasing the risk of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), making it less ideal during CPB. It is also associated with a higher risk of viral infections.4

- Alternative coagulation strategies:

- If AT supplementation and increased heparin dosing fail to raise the ACT to a therapeutic level, alternative coagulation agents, such as direct thrombin inhibitors (e.g., bivalirudin or argatroban), may be considered.

- These can be effective for patients with confirmed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and those with heparin resistance.

- These anticoagulation strategies allow for anticoagulation without reliance on AT but do come with several pitfalls, such as the lack of standardized protocols for CPB, short half-life (bivalirudin) requiring modifications to CPB circuits to prevent stasis and thrombosis, and lack of a specific reversal agent, increasing the risk of surgical bleeding.

- Alternatives to CPB:

- Off-pump surgeries can be considered if none of the aforementioned techniques or strategies fail to achieve a therapeutic ACT level.

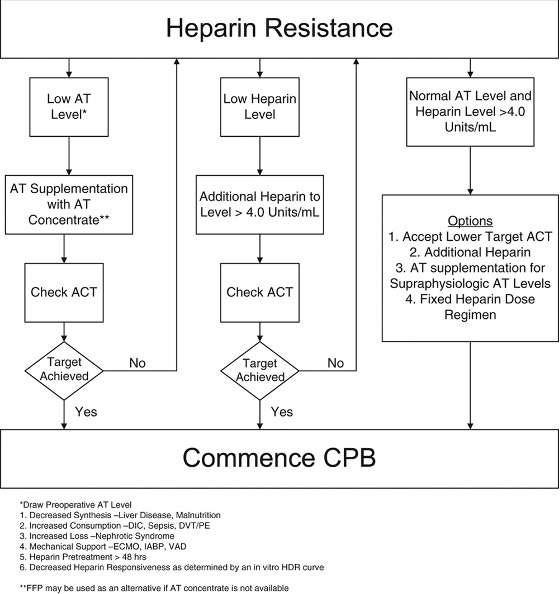

- An algorithm for the management of heparin resistance is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Algorithm for the management of heparin resistance. Used with permission from Finley A et al. Anesth Analg 2013.4

References

- Levy JH, Connors JM. Heparin resistance—Clinical perspectives and management strategies. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385:826-32. PubMed

- Crochemore T, Görlinger K, Lance, MD. Early goal-directed hemostatic therapy for severe acute bleeding management in the intensive care unit: A narrative review. Anesth Analg. 2024;138(3):499-513. PubMed

- Chen Y, Hui P, Hwang NC. Heparin resistance during cardiopulmonary bypass in adult cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2024; 36:4150-60. PubMed

- Finley A, Greenberg C. Heparin sensitivity and resistance: Management during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 2013;116(6):1210-22. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.