Copy link

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

Last updated: 02/19/2025

Key Points

- Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) often presents with acute onset of ascending, symmetric, flaccid paralysis with decreased deep tendon reflexes. In most cases, it follows a respiratory or gastrointestinal infection.

- Anesthesiologists may see patients with GBS in the intensive care unit (ICU) or for operative procedures such as tracheostomies, and they must assess and manage hemodynamic instability, autonomic dysfunction, and respiratory insufficiency to mitigate negative outcomes.

- Succinylcholine should be avoided due to the risk of hyperkalemia and cardiac arrhythmias, and direct adrenergic agents (e.g., norepinephrine) should be used over indirect sympathomimetics (e.g., ephedrine).

- Intravenous immunoglobulin and plasma exchange are equally effective therapies for treating GBS.

Introduction

- GBS is the most common cause of acute flaccid paralysis and occurs in 1-2 per 100,000 patients each year, with a yearly incidence of 100,000 new cases globally.1

- GBS is an acute immune-mediated polyradiculoneuropathy. Its presenting symptoms are heterogeneous and often associated with a triggering illness, though in rare cases, it can also be triggered by oncologic drugs or surgery.2

- Nearly 5% of patients with GBS die from complications of the disease, such as pneumonia, aspiration, deep vein thromboses, or autonomic dysfunction. Nearly 20% of patients cannot walk independently at 1 year.1

Pathophysiology

- In more than 70% of cases, GBS occurs within 4 weeks of a respiratory or gastrointestinal infection.3 The immune response to the infectious disease is believed to be cross-reactive with shared epitopes on peripheral nerves, a process called molecular mimicry. For this reason, the presentation of GBS can be variable depending on the triggering infection and the portion of the nerve that is cross-reactive with infectious antigens.4

- Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP) is one prominent form of GBS.

- This subtype is more associated with respiratory infection caused by multiple possible agents, including cytomegalovirus, H. influenzae, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Epstein-Barr virus, influenza A virus, and Zika virus.

- This subtype is more common in Europe and North America.

- In general, it is associated with a localized inflammatory response against Schwann cells, which leads to the demyelination of peripheral nerves, including cranial nerves.4

- In rarer cases, GBS can present as an acute motor axonal neuropathy or acute motor and sensory axonal neuropathy.4

- More common in Bangladesh and Northern China, this variant is sometimes triggered by gastrointestinal infection with C. jejuni.

- Direct damage to axons and not just myelin results in a different phenotype for GBS.

- While much is known about GBS, it is currently unclear whether specific immune responses or antibodies are solely responsible for the widely heterogenous presentations, including some variants such as Miller-Fisher syndrome and Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis, which clinically appear distinct but share serologic similarities with GBS.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- GBS can be challenging to diagnose due to its multiple presenting subtypes. Accurate diagnosis usually requires a detailed clinical history and time course, a comprehensive neurologic exam, and confirmatory laboratory studies.

- In most cases, GBS progresses rapidly over two weeks and peaks within four weeks of symptom onset.4 Over 70% of GBS cases are preceded by a respiratory or gastrointestinal infection.

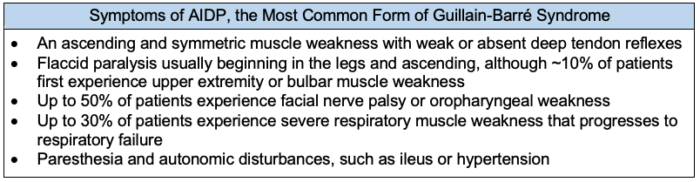

- The most common subtype, AIDP, also known as the classic demyelinating subtype, usually presents as ascending, symmetric, flaccid paralysis with decreased deep tendon reflexes. Sensory symptoms are common, though generally milder than motor symptoms. Cranial nerve involvement and autonomic dysfunction are also common, and respiratory symptoms can necessitate intubation and mechanical ventilation. Table 1 shows the common symptoms of this subtype.

- Common supporting studies for the diagnosis of GBS include elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein with relatively normal white blood cells (WBCs) (albuminocytologic dissociation, usually seen after the first week of symptoms) and nerve conduction studies that confirm slowed conduction or nerve block.

- Less common variants of GBS include pure motor or pure sensory variants, those affecting only the lower or upper limbs, bulbar variants, variants with hyperreflexia instead of hyporeflexia, variants with ataxia and ocular symptoms (Miller-Fisher syndrome), and variants with CNS involvement (Bickerstaff brainstem encephalitis).

Table 1. Symptoms of acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP). AIDP is the predominant subtype of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) in North America and Europe, encompassing 60 – 80% of GBS cases. AIDP accounts for 35 – 70% of GBS cases in Asia, Central America, and South America.5

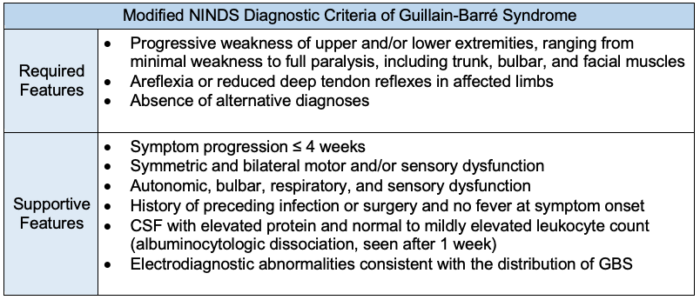

- Currently, the modified National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke diagnostic criteria are most commonly used in clinical practice. Diagnosing GBS requires multiple factors, which may be accompanied by various supportive diagnostic symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2. Diagnostic criteria of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). The diagnosis of GBS is primarily clinical and may be supported by CSF analysis and autoantibody testing. Electrodiagnostic and imaging studies and serum laboratory testing are used to exclude other causes of acute weakness.4,6 NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

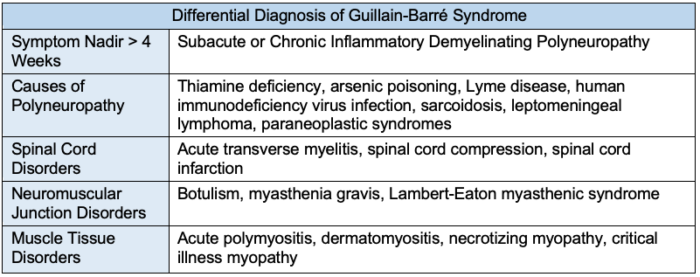

- Due to the difficulty of diagnosing GBS, other causes of a patient’s symptoms should be considered if the patient’s symptoms peak within 24 hours of onset, if there is a sharp sensory level, or if the certainty of diagnosis for GBS is low (Table 3).

Table 3. Differential diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Other causes of polyneuropathy should be considered if: symptoms reach nadir within 24 hours or after 4 weeks; there is an identifiable sensory level; weakness presents asymmetrically; fever at onset; bowel or bladder dysfunction at onset; respiratory dysfunction without limb weakness; and CSF leukocyte count more than 50/mm3.4,6

Treatment and Management

- Upon admission, the patient’s neurologic, respiratory, and hemodynamic status should be monitored.6,7 During the acute phase of illness, symptoms can progress rapidly and may need frequent re-evaluation.

- Neurologic: Limb, facial, bulbar, and neck strength; speech and swallow evaluation; bowel and bladder continence.

- Respiratory: Respiratory rate; oxygen saturation; forced vital capacity; negative inspiratory force or maximal inspiratory force.

- Hemodynamics: Heart rate; arrhythmias; blood pressure; fluid status.

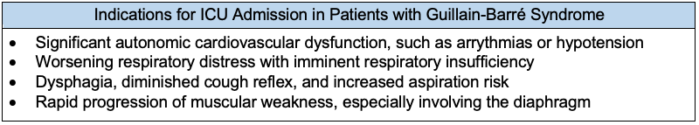

- Individuals with GBS may require admission to the ICU in severe cases (Table 4).6,7

- Up to 22% of patients may require intubation and mechanical ventilation.6

- The Erasmus GBS Respiratory Insufficiency Score (EGRIS) can help predict the probability of a patient requiring intubation within one week of assessment.6 This score includes the days between symptom onset and hospital admission, whether or not the patient has facial or bulbar weakness, and a summary score that tests strength in six standardized muscle groups.

- Impending respiratory insufficiency can be assessed clinically by observing the use of accessory breathing muscles, tachypnea, a diminished vital capacity of less than 15-20 mL/kg, or a decreased negative inspiratory force. Abnormal arterial blood gas or pulse oximetry measurements are late signs of impending respiratory failure and are not required for intubation.

Table 4. Intensive care indications in Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS). Patients with GBS should be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) when there is evidence of cardiovascular instability or respiratory failure.6

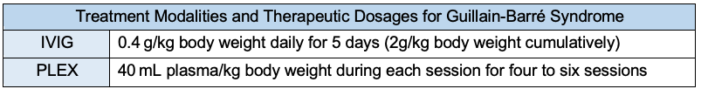

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and plasma exchange (PLEX) are the two therapies proven to treat GBS, and neither treatment has been shown to be superior to the other (Table 5).

- Corticosteroids have not been shown to improve outcomes when given for GBS, and oral corticosteroids may even negatively impact outcomes.4,6

Table 5. Treatment modalities and therapeutic dosages for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and plasma exchange (PLEX) have been shown to be equally effective in treating GBS. However, no additional benefit has been shown when delivering both IVIG and PLEX. The selection of therapy should be driven by available resources and ease of administration. Possible complications following IVIG include hemolytic anemia, transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), and anaphylaxis. Complications following PLEX include electrolyte disturbances, hypothermia, and TRALI.6,7

- Care should also be taken to mitigate the complications of GBS.

- Examples of complications include pressure ulcers, hospital-acquired infections, deep vein thrombosis, dysphagia, corneal ulceration, limb contractures, pain, anxiety, hallucinations, and depression.6

- Pharmacologic antithrombotic prophylaxis can reduce the risk of deep vein thrombosis in this population of patients.

- Bulbar weakness can often limit nutritional intake, requiring supplemental enteral nutrition.

- Approximately 80% of patients will regain the ability to walk independently 6 months after disease onset.

- However, death may occur in up to 10% of patients.6

- Patients may take more than 5 years to recover from residual weakness, fatigue, and neuropathic pain.6

- Up to 5% of patients may experience a recurrence of GBS, which is greater than the 0.1% lifetime risk of developing GBS in the general population.6

- Patients whose symptoms reach a nadir later than four weeks may have subacute or chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, which requires different management approaches.7

- Clinical prognostic tools, like the Erasmus GBS outcome score (EGOS) and modified Erasmus global outcome score (mEGOS), can be used to estimate the probability of being unable to walk after 6 months.7

Anesthetic Considerations

- In patients with GBS, the anesthetic plan must be tailored to avoid inciting hemodynamic and autonomic instability.8,9

- Adequate fluid resuscitation can reduce hypotension under anesthesia.

- Bowel and bladder dysfunction can be linked to autonomic instability in other populations and should be treated in GBS.

- Regional, neuraxial, and general anesthesia may all be appropriate anesthetic options for patients with GBS who undergo surgery.10

- While there are few case reports of GBS onset after neuraxial anesthesia, it is not believed that neuraxial anesthesia worsens GBS symptoms.

- In the largest observational case series to date (N=103 patients), which compared patients who had undergone lower extremity orthopedic surgery under either general or neuraxial anesthesia, no significant difference was found in the length of postanesthesia care unit stay, hospital admission, or time to achieve physical therapy milestones.10

- Patients with GBS are reportedly more sensitive to local anesthetics.9 Parturient patients with GBS have been reported to require lower doses of epidural anesthesia compared to non-GBS patients in labor. However, dose-finding studies in this population have not been completed.9

- Local anesthetics for neuraxial anesthesia in these patients may lead to hemodynamic instability since GBS already predisposes patients to autonomic dysfunction.9

- Succinylcholine should be avoided due to the risk of developing hyperkalemia and subsequent arrhythmias or cardiac arrest.8,9

- This risk is increased because muscle denervation upregulates the transcription of postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors, which increases the body’s sensitivity to succinylcholine.9

- Nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents, like rocuronium and vecuronium, are safer to use in patients with GBS since there is a lower risk of developing hyperkalemia.9

- However, nondepolarizing neuromuscular blockers may lead to prolonged postoperative ventilation.8

- Direct adrenergic agents, like norepinephrine, should be used instead of indirect sympathomimetics, like ephedrine,8 because indirect sympathomimetics may lead to unpredictable effects due to GBS-driven autonomic dysfunction.8

- In patients who have a rapid onset of respiratory failure, early tracheostomy should be considered to optimize pulmonary rehab and recovery.

References

- Shahrizaila N, Lehmann HC, Kuwabara S. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 2021;397(10280):1214-28. PubMed

- Zhong YX, Lu GF, Chen XL, Cao F. Postoperative Guillain-Barré Syndrome, a Neurologic Complication that Must Not Be Overlooked: A Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2019; 128:347-53. PubMed

- Goud R, Lufkin B, Duffy J, et al. Risk of Guillain-Barré Syndrome Following Recombinant Zoster Vaccine in Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(12):1623-30. PubMed

- Chandrashekhar S, Dimachkie MM. Guillain-Barré syndrome in adults: Pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis. Guillain-Barré syndrome in adults: Pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis. In: UpToDate. 2024. Accessed October 15, 2024. Link

- Van Den Berg B, Walgaard C, Drenthen J, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(8):469-82. PubMed

- Leonhard SE, Mandarakas MR, Gondim FAA, et al. Diagnosis and management of Guillain–Barré syndrome in ten steps. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(11):671-83. PubMed

- Muley SA. Guillain-Barré syndrome in adults: Treatment and prognosis. Guillain-Barré syndrome in adults: Treatment and prognosis. In: UpToDate. 2024. Accessed October 15, 2024. Link

- Kim H, Ryu J, Hwang JW, Do SH. Anesthetic management for cesarean delivery in a Guillain-Barré syndrome patient -A case report-. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64(3):268-71. PubMed

- Paul A, Bandyopadhyay K, Patro V. Anesthetic management of a parturient with Guillain-Barre syndrome posted for emergency caesarian section. J Obstet Anaesth Crit Care. 2012;2(1):40. Link

- Tra BM, Haidar J, Lauzadis J, Illescas A, Lee D. Is Spinal Anesthesia Safe in Patients with a History of Guillain-Barré Syndrome Undergoing Orthopedic Surgery? In: Proceedings from the 49th Annual Regional Anesthesiology and Acute Pain Medicine Meeting. 2024: Abstract 5499. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.