Copy link

Geriatric Anesthesia: Definitions, Demographics, Frailty, Morbidity and Mortality, and Informed Consent

Last updated: 09/27/2023

Key Points

- "Older adults" is the preferred term to describe patients aged 65 years and older and currently comprise 16% of the population. Older adults are expected to make up 21.6% of the population by 2040, with continued increases through 2060.

- Frailty is an age-associated decline in multiple physiologic processes and is associated with poor health outcomes. There is no gold standard measurement of frailty, but multiple clinical assessment tools are available.

- Older adults are at an increased risk of perioperative complications, which subsequently predisposes to significantly increased morbidity and mortality. Frail older adults are at an even higher risk of complications and poor outcomes.

- Informed consent in older adults may be complex due to confounding cognitive decline and medical comorbidities.

Definitions and Demographics

- Geriatrics is the branch of healthcare that provides care to older adults. Gerontology is the study of aging and encompasses a complete bio-/psycho-/social model of aging.1

- The term “older adults” is the preferred term to describe patients with advanced age as other terms such as “elderly,” “seniors,” or “senior citizens” are considered outdated and ageist.2 Typically, those 65 years and older are classified as older adults, although there is no specific age cutoff. The ambiguity in defining this patient demographic is partially attributable to the fact that chronological age does not necessarily equal physiological functional ability, which is related to frailty (see below) and can be affected by multiple factors such as comorbidities, genetic predispositions, lifestyle (diet, exercise, sleep), environmental factors, and socioeconomic status.

- In 2020, there were 55.7 million Americans 65 years and older, which comprised 17% of the population, or more than 1 in 6 persons.3

- In 2020, persons 65 years old had an average additional life expectancy of 18.5 years.

- As advances in technology and healthcare continue to improve, the population of older adults is expected to increase drastically over the next few decades, and older adults are expected to make up 22% of the population by 2040, with continued increases through 2060.3

Frailty

- While there is no standardized definition of frailty, Xue et al. have eloquently described frailty as “a clinically recognizable state of increased vulnerability resulting from aging-associated decline in reserve and function across multiple physiologic systems such that the ability to cope with everyday or acute stressors is comprised.”4 Surgical stress is one such acute stressor that can have significantly deleterious implications on the health of older adults exhibiting more frailty than others.

- Although understanding the gestalt of frailty and its implications on perioperative care is critical, there is no gold standard measure of assessing frailty. However, multiple assessment tools have been described in the literature.

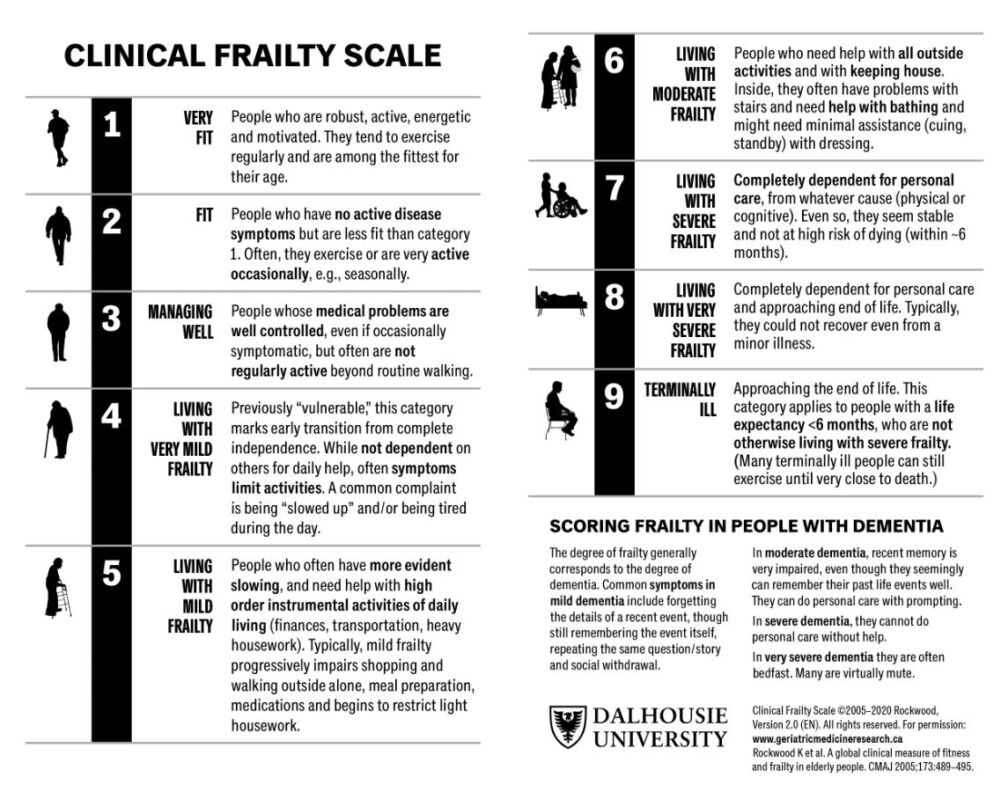

- The first is the Clinical Frailty Score by Rockwood et al. in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CSHA). This tool is easily applied from a detailed patient interview with a focus on functional capacity and activities of daily living5 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Clinical Frailty Scale; used with permission from Geriatric Medicine Research, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada

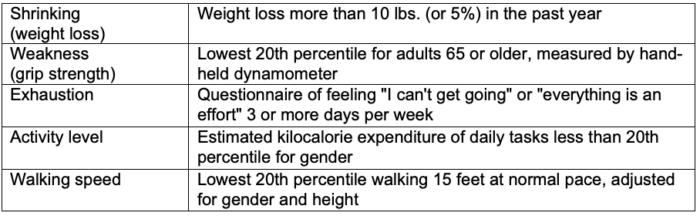

- Another is the Frailty Criteria developed by Makary et al. which evaluates frailty in five domains (Table 1).6 Each domain is scored 0 or 1.

Table 1. Criteria for frailty. Adapted from Makary MA, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(6):901-8.6

- In one study, frail older adults had an increased risk of postoperative complications (odds ratio up to 2.54), increased hospital length of stay (incidence ratio 1.69), and greater likelihood of discharge to skilled nursing after previously living at home (odds ratio 20.48).6 Additionally, frail older adults had increased postoperative mortality risk (hazard ratio 9.01) and longer hospital stays than nonfrail older adults.7

Morbidity and Mortality

- Advanced age is an independent risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality for all surgical procedures. Age is associated with increased prevalence and severity of medical comorbidities.

- The Veterans Affairs National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP) showed that patients 80 years or older have higher all-cause mortality at 30 days in noncardiac surgery compared to patients younger than age 80 (8% vs. 3%). Additionally, older adults experienced more perioperative complications compared to younger adults, the most common of which being pneumonia (5.6%), urinary tract infections (5.6%), mechanical ventilation more than 48 hours (3.5%), reintubation (2.8%), cardiac arrest (2.1%), and sepsis (2.0%). Of the older adults who suffered one or more perioperative complications, mortality rates increased significantly to 26-33%.8

Informed Consent

- The convention of informed consent mandates that prior to any medical treatment, a patient must be given adequate information (in lay terms) regarding the illness and procedure, including benefits and risks of treatment, alternatives to treatment, and consequences of not receiving treatment. Additionally, patients must make these decisions voluntarily without coercion or duress, which can pose difficulty in the acute perioperative period as acute severe pain can potentially place patients in a state of duress. Finally, patients must have the decision-making capacity in order to make such a decision, which is described below.9

- In order for a patient to provide informed consent, they must have the mental capacity to make decisions. Given the many comorbidities associated with mental deterioration in aging, this is especially important to evaluate for older adults prior to surgery. Capacity is one’s ability to make a decision and is constituted by the following four attributes: understanding, expressing a choice, appreciation, and reasoning. In understanding, patients must be able to explain in their own words the meaning of the information provided. They must be able to state a specific decision, even if that decision is contrary to the opinions of healthcare providers. They must demonstrate appreciation for the implications of illness and treatment and explain how information applies to their situation, which can be related to diagnosis, benefits, or risks of treatment. Finally, they must demonstrate reasoning and the ability to understand the consequences or benefits of decisions.10

- Obtaining informed consent in the older adult population can be complex and confounded by age-related cognitive dysfunction (i.e., Alzheimer’s), altered mental status from infectious or metabolic processes, iatrogenic delirium, and other comorbidities. If there is any doubt whether or not an older adult patient is appropriate for consent, a full assessment of mental capacity should be obtained and/or consent discussed with the patient’s Medical Durable Power of Attorney.

References

- Stefanacci RG. Physical changes with aging. Merck Manual. Reviewed/Revised May 2022. Accessed Aug 2023. Link

- Lundebjerg NE, Trucil DE, Hammond EC, et al. When it comes to older adults, language matters: Journal of the American Geriatrics Society adopts modified American Medical Association Style. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(7):1386-8. PubMed

- The Administration for Community Living, United States Department of Health and Human Services. 2021 Profile of Older Americans. Published Nov 2022. Accessed Aug 2023. Link

- Xue QL. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27(1):1-15. PubMed

- Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489-95. PubMed

- Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(6):901-8. PubMed

- Kim SW, Han HS, Jung HW, et al. Multidimensional frailty score for the prediction of postoperative mortality risk. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(7):633-40. PubMed

- Hamel MB, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, et al. Surgical outcomes for patients aged 80 and older: morbidity and mortality from major noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):424-9. PubMed

- Norman, GAV. Ethical challenges in the anesthetic care of the geriatric patient. ASA Syllabus on Geriatric Anesthesiology. 2002; 58-9. Link

- Sadoff R. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: A guide for physicians and other health professionals. Psychiatric services (Washington, DC). 1999;50(3):425-6. Link

Other References

- Stefanacci RG. Physical Changes With Aging. Merk Manual Professional Version. Updated: September 2022. Accessed Date: September 27, 2023. Link

- Rockwood et al. Clinical Frailty Scale. Geriatric Medicine Research. Published: 2005. Accessed: September 27, 2023. Link

- ASA Committee on Geriatric Anesthesia. Syllabus on Geriatric Anesthesiology. Published: January 10, 2002. Accessed: September 27, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.