Copy link

Gastroschisis and Omphalocele

Last updated: 03/30/2023

Key Points

- Gastroschisis and omphaloceles represent congenital defects of the abdominal wall. They differ in their presentation (peritoneal covering) and location relative to the umbilical cord.

- Timing and staging of repair vary depending on the diagnosis, severity (size, amount of herniation, etc.), and multi-organ involvement.

- Anesthetic management requires special attention to temperature control, glucose management, blood volume/loss, pain control, and physiology of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems.

Definitions and Differences

Gastroschisis

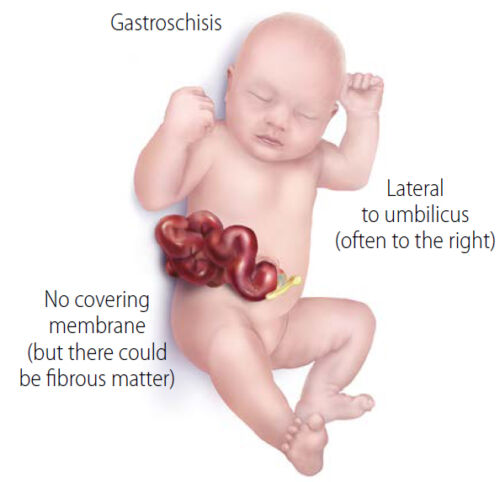

- Gastroschisis is a full thickness abdominal defect that usually presents to the right of the umbilicus (Figure 1). Left-sided duplication of the defect can occur but is rare.1,2

- Variable amount of intestine and other abdominal organs can herniate WITHOUT a covering membrane or peritoneal sac.

- Umbilical cord insertion is unaffected.

- Ten to 20% of cases have associated anomalies, with the most significant being gastrointestinal anomalies, such as intestinal stenosis or atresia. Other anomalies include undescended testes, Meckel’s diverticulum, and intestinal duplication.

- Chromosomal abnormalities are uncommon.

- Prognosis depends on the condition and amount of herniated bowel; survival rates are greater than 90%.1

Figure 1. Gastroschisis - Abdominal contents herniating through anterior abdominal wall defect without membrane coverage. Umbilical cord is seen to implant directly into the umbilicus. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Link.

Omphalocele (or exomphalos)

- Abdominal contents herniate through the defect but are covered with a membrane (Figure 2). Size of the defect and amount of herniation is variable.2

- The midline abdominal wall defect can be centered in the upper, mid, or lower abdomen.

- The umbilical cord attaches to the membrane of the omphalocele.

- There is a high incidence (50-70%) of associated anomalies.1-3

- Multiple anomalies usually lead to stillbirth.

- Cardiac defects occur in 30-50% of cases; Atrial septal defects and tetralogy of Fallot are most common.

- May be clustered in syndromic patterns.

- Beckwith-Wiedemann

- Marshal-Smith

- Meckel Gruber

- Pentalogy of Cantrell

- It less commonly presents with renal/bladder/cloacal defects, cleft lip/palate, and skeletal lesions.

- Chromosomal abnormalities are common (Trisomy 13, 14, 15, 18, 21).

- Prognosis depends on the severity of associated anomalies; survival rates range from 40-70%.3

Figure 2. Omphalocele – Gastric contents herniate outside of abdominal wall but are contained within a membrane into which the umbilical cord attaches. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Link

Diagnosis

- Abdominal wall defects are commonly diagnosed via ultrasound during prenatal screening. Prenatal ultrasound has high specificity (95%) but lower sensitivity (60-75%) due to variability in positioning of the baby and sonographer skill.1

- Maternal serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) may be elevated in cases where an abdominal wall defect is present. Gastroschisis tends to have a higher value when compared to omphalocele.1

Epidemiology, Embryology, and Pathophysiology

- Gastroschisis occurs in 3-4 per 10,000 births.1

- Omphalocele occurs in 1.5-3 per 10,000 births.1

- Both are sporadic in nature, but rare familial and potentially genetic causes have been described.

- Abdominal wall defects are thought to occur when the intestinal tract migrates out of the abdominal cavity into the umbilical cord during the 6th week of gestation with subsequent failure of the intestine to return during the 10th-12th week of gestation.2

- Gastroschisis is thought to be caused by an ischemic insult to the developing body wall which leads to degeneration and failure of the anterior wall to close.

- In omphalocele, the bowel fails to return to the abdomen and remains in the umbilical cord, likely secondary to failure of abdominal wall in-folding.

Prenatal Management

- Gastroschisis is considered a high-risk pregnancy with high risk of prenatal complications.2

- Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR)

- Fetal death

- Premature delivery

- Gastroschisis has a high-risk of bowel injury (serositis/inflammation), volvulus, oligohydramnios, and fetal asphyxia and death. Early delivery of fetus may be considered before complications arise.1

- Cesarean delivery is commonly carried out with either defect to prevent further damage to the bowel, or other herniated organs, and prevent dystocia during labor.2,3

Surgical repair - For both defects, the goal is to reduce the herniated contents into the abdomen and close the fascia and skin to create a solid abdominal wall.1,3

- Variables affecting treatment include

- size;

- type of defect;

- size of baby; and

- associated anomalies and comorbidities.

Gastroschisis

- After delivery and newborn resuscitation, the exposed bowel is wrapped with sterile saline dressings and wrapped in a plastic wrap. Some centers place the entire viscera and the entire lower half of the baby into a transparent plastic bag.1 This prevents fluid and heat losses that can lead to metabolic derangements.3

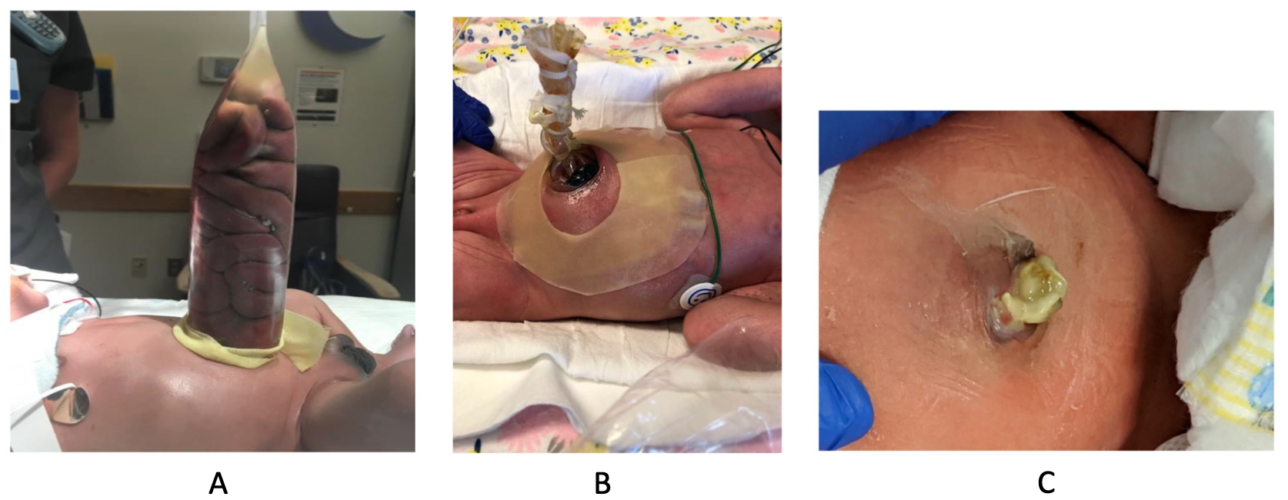

- Options for surgical repair include primary closure vs. using a prefabricated spring-loaded silo for staged reduction (Figure 3 A and B). A sutureless closure technique for primary closure is gaining popularity, which uses the umbilical cord as a biologic dressing. After reducing the bowel, the defect is covered with the umbilical cord and a clear plastic dressing, which is then allowed to heal via secondary intention (Figure 3C).

- During surgical repair, the bowel is inspected for atresia, necrosis, or vascular compromise.

- Most commonly closure occurs in a staged fashion where the silo is placed, and serial reduction is performed after bowel edema decreases. The goal is to complete the closure within 7-10 days.1

Figure 3. Staged reduction of gastroschisis (A&B). A: Bowel loops placed in a silo, B: Serial reduction of bowel loops, C: Primary sutureless closure of gastroschisis. Source: Bhat V, Moront M, Bhandari V. Gastroschisis: A state-of-the-art review. Children (Basel). 2020l 7(12): 302. Link. CC BY 4.0.

Omphalocele

- The initial newborn resuscitation and medical management is similar to patients with gastroschisis.

- Covering the sac allows for protection of herniated contents.1,3

- However, there is no urgency to perform operative closure if the membrane is intact.

- Covering allows for complete evaluation and potential treatment of associated anomalies.

- Primary closure vs epithelization of the sac

- If primary closure is not feasible, epithelization of the sac is permitted.

- Silver sulfadiazine is applied to the membrane which allows for epithelization.

- After several months and when the sac is sturdy, the abdominal contents are reduced, and a ventral hernia repair is performed.1

- Closure can occur within 6-12 months.1

Anesthetic Management and Implications

Preoperative Considerations

- Complete blood cell count and type and screen for surgery; blood loss is usually minimal but transfusions may be required for larger defects.

- Metabolic profile with correction of electrolyte derangements prior to surgery

- Complete evaluation of associated anomalies (cardiac, renal, skeletal, etc.)

- Surgery should be delayed until electrolyte, hemodynamic, and cardiopulmonary issues have been addressed.1,3

- Nasogastric suction should be utilized to decompress the stomach and prevent pulmonary aspiration.3

Intraoperative Considerations

- Standard American Society of Anesthesiologists monitors including temperature monitoring should be performed.

- Due to the defect a large amount of heat loss and insensible losses will occur.

- Induction

- The baby should be positioned in a slight reverse Trendelenburg position to allow herniated contents to rest away from the chest.

- Strategies for rapid intubation should be utilized to prevent aspiration; there is an increased risk in both gastroschisis and omphalocele.3

- Increased risk of desaturation is possible due to potential pulmonary hypoplasia, incomplete alveolar maturation, and increased oxygen demand.3

- Maintenance

- Combination of inhaled or intravenous anesthetics can be used to maintain general anesthesia.

- Nitrous oxide should be avoided.

- Neuromuscular blockade supports abdominal wall closure and ventilation.

- Closure of the defect can cause decreased diaphragmatic excursion, compression of the lungs, and an increase in airway pressures. Close communication with the surgeon and assessment of intraabdominal pressures is critical to avoid the development of abdominal compartment syndrome.

- Lines

- Adequate intravenous access to allow for appropriate resuscitation

- Arterial catheter for close monitoring of hemodynamics, intravascular volume, respiratory parameters, and electrolyte abnormalities

- Central line placement (peripherally inserted central catheter vs. central venous catheter) should be considered for fluid management and postoperative total parenteral nutrition (TPN).3

- Clinicians should monitor intravascular volume and consider replacement (fluid vs. blood) based on surgical blood loss, urine output, and blood pressure.3

- Glucose should be monitored closely and corrected as needed.3

Postoperative Considerations

- The patient should be transported to the neonatal intensive care unit for close monitoring of respiratory and cardiovascular function. Most of these neonates require ventilation in the immediate postoperative period.3

- Intraabdominal pressures must be monitored. Increased pressures can lead to respiratory insufficiency and decreased organ/bowel perfusion.1,3

- Prompt and early feeding has been associated with decreased TPN days, decreased length of stay, and less infections.3

- Close electrolyte monitoring should be continued. Nutrition and total fluid administration should be modified to avoid further issues.

References

- Ledbetter DJ. Congenital abdominal wall defects and reconstruction in pediatric surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2012;92(3):713-27. PubMed

- Ledbetter DJ. Gastroschisis and Omphalocele. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86(2):249-60. PubMed

- Roberts RJ, Lukula D, Sandler A. Anesthetic and surgical dilemmas during repair of congenital abdominal wall defects – gastroschisis/omphalocele in newborns. In: Verghese, ST, Kane TD. (eds) Anesthetic Management in Pediatric General Surgery. Springer, Cham. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.