Copy link

Emergence Delirium in Children

Last updated: 10/16/2023

Key Points

- Emergence delirium (ED), also known as emergence agitation, is a postoperative complication affecting pediatric patients emerging from general anesthesia. ED may put patients, parents, and healthcare providers at risk for physical, emotional, and economical complications.

- While the etiology of ED is not completely understood, the risk factors for ED include preschool-aged children, use of low-soluble volatile anesthetics, preoperative anxiety, and certain surgeries.

- While most cases of ED is self-limited and resolves on its own, pharmacological therapy may be indicated.

Introduction

- ED is an altered state of consciousness that may occur as a child awakens or emerges from general anesthesia that manifests as disorientation, hyperactive behavior, and hypersensitivity in the immediate postoperative period.1

- The term emergence agitation is often used interchangeably with ED.2

- The incidence of ED in current pediatric anesthesia practice in unclear.1 Older studies reported an incidence ranging from 2-80%. The current practice of administering preemptive analgesics, sedatives (dexmedetomidine), and other medications has reduced the incidence of ED.1

- The incidence of ED depends on several factors, including the age of the child, type of anesthetic used, nature of surgery or procedure, and the diagnostic criteria used.1

- ED typically occurs soon after emergence from general anesthesia but can be delayed up to 45 minutes.3 It usually presents as agitation, nonpurposeful movement, including kicking, pulling, and flailing, as well as lack of eye contact and self-awareness.3

- Although usually self-limited, ED can cause both physical and emotional distress to both patients and caregivers.

- The effects of ED may cause behavioral changes even after discharge, such as general anxiety, separation anxiety, sleep anxiety, bed wetting, eating disturbances, aggression against authority and apathy/withdrawal.4

- Physical harm can occur to the patients as well as to parents and healthcare workers.

- Care must be taken to maintain intravenous lines, as well as surgical dressings, and drains.

- The sight of ED can be distressful to both parents and healthcare workers, as well as other patients in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU).

- ED can also increase healthcare costs due to prolonged PACU stays as well as need for interventions, including surgical repair and pharmacologic treatments.

Etiology and Risk Factors

- The causes of ED, while still unknown, may be multifactorial.

- It has been postulated that ED occurs secondary to the rapid redistribution of the anesthetic. However, the rapid emergence from general anesthesia has been inconsistently associated with the risk of ED.1,3

- Inhalational anesthetics, specifically sevoflurane, caused excitation of locus ceruleus neurons in mice, an area involved in adrenergic excitation; thus, this property may be involved as well in the etiology of ED.5

- There are several risk factors for ED.

- Age: ED is most commonly seen in preschool children, aged 2 to 6 years of age.1-3

- Gender: There have been mixed conclusions with some studies showing a predisposition for male patients, while others have shown no differences between males and females.3

- Type of surgery: Certain procedures, such as ear, nose and throat and eye surgeries may predispose to ED.2,3

- Anesthetic agent: The newer, less soluble volatile anesthetics, sevoflurane and desflurane, have increased the incidence of ED. The order of anesthetics most likely to be associated with ED are sevoflurane > desflurane > isoflurane > propofol > halothane.1

- Interactions with health care providers: Careful examination of interactions between parents, their children, and health care providers using real-time evaluation and 5-point scoring system called the Perioperative Adult Child Behavioral Interaction Scale (PACBIS) revealed negative interactions and coping corelate with a higher incidence of ED.6

- Preoperative anxiety: Anxiety in both patients and parents may increase the risk of ED.

- Pre-existing behaviors: As anxiety is a risk factor for ED, those who exhibit certain behaviors and temperament tend to be at greater risk for preoperative anxiety.4

- The duration and depth of anesthesia has no effect on the risk of ED.1

- The duration of deep anesthesia (bispectral index less than 45) has no effect.

- ED is as likely to occur after brief procedures (e.g., tympanostomy and tubes) as it is after longer surgeries.1

Diagnosis

- ED is a clinical diagnosis. During the episode, the child is often agitated, inconsolable, flailing their arms, and not making eye contact.

- The diagnosis of ED is often confounded by postoperative pain. However, studies have shown that ED can occur after nonpainful procedure (i.e., MRI scans) when performed using volatile anesthetics.8

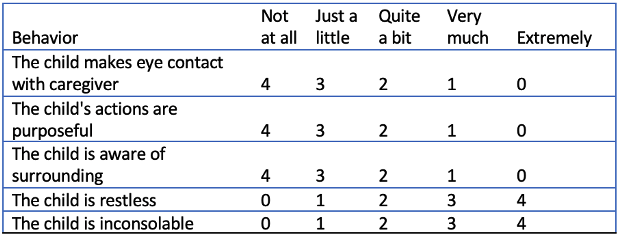

- The Pediatric Anesthesia Emergence Delirium (PAED) scale, developed by Sikich and Lerman, is a validated tool to diagnose ED.9 The PAED scale consists of five behaviors, each of which is rated on a five-level scale of zero to four. (Table 1). A score greater than 10 is indicative of an ED diagnosis that warrants intervention.

Table 1. Pediatric anesthesia emergence delirium scale

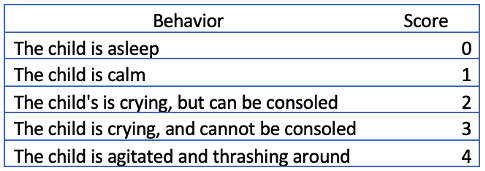

- An alternative and simpler Watcha scale grades the patient from asleep to agitated to thrashing (Table 2).10 However, it has not been validated.

Table 2. The Watcha scale for ED

- The differential diagnosis of ED includes1

- Pain

- Hypoxia

- Hypo or hypercarbia

- Hypoglycemia

- Hypotension

- Increased intracranial pressure

Treatment

- ED is usually self-limited and can resolve without pharmacologic intervention.

- The child should be assessed for potentially dangerous causes of agitation listed in the differential diagnosis section.

- Most ED resolves with support and prevention of harm. Parents and caregivers should be included in the treatment decisions whenever possible.

- Pharmacologic treatment of ED most often includes intravenous administration of the following medications.1-3

- dexmedetomidine (0.3-0.5 mcg/kg slow bolus)

- propofol (0.5-1mg/kg)

- opioids (fentanyl 1-2 mcg/kg)

Prevention

- Prophylaxis against ED has been shown to be more beneficial than postoperative treatment.

- Pharmacologic treatment preoperatively and intraoperatively has been shown to help reduce the incidence of ED.

- Total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) has also been shown to be effective in reducing ED when compared to the use of volatile anesthetics.

- Drugs shown to help reduce the incidence of ED include opioids (i.e., fentanyl, remifentanil, and sufentanil), propofol, dexmedetomidine, clonidine, and ketamine.1-3

- Of note, the effects of preoperative benzodiazepine (i.e., midazolam) in preventing the incidence of ED have been inconsistent.

- Benzodiazepines, particularly midazolam, are used frequently as premedication to reduce anxiety in the pediatric population, since preoperative anxiety is believed to contribute to ED its use may be beneficial in prevention.1

- Several studies looking at nonpharmacologic interventions to decrease the incidence of ED by reducing preoperative anxiety have shown mixed results or shown no benefit.3

- Parental presence during induction

- Virtual tours prior to surgery

- Video distraction/tablet-based interactions during mask induction of anesthesia.

References

- Lerman J. Emergence delirium and agitation in children. In: Post T (ed). UpToDate. 2023. Accessed August 10th, 2023. Link

- Mason KP. Paediatric emergence delirium: a comprehensive review and interpretation of the literature. Br J Anaesth.2017; 118(3): 335–43. PubMed

- Dahmani S, Delivet H, Hilly J. Emergence delirium in children: an update. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2014; 27(3):309-15. PubMed

- Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Maranets I, et al. Preoperative anxiety and emergence delirium and postoperative maladaptive behaviours. Anesth Analg. 2004; 99:1648–54. PubMed

- Stoicea N, McVicker S, Quinones A, et al. Delirium-biomarkers and genetic variance. Front Pharmacol. 2014; 5:75. PubMed

- Sadhasivam S, Cohen LL, Szabova A, et al. Real-time assessment of perioperative behaviors and prediction of perioperative outcomes. Anesth Analg. 2009;108(3): 822–6. PubMed

- Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Weisman SJ, et al. Social adaptability, cognitive abilities, and other predictors for children’s reactions to surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2000; 12: 549–54. PubMed

- Abu-Shahwan I. Effect of propofol on emergence behavior in children after sevoflurane general anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18: 55–59. PubMed

- Sikich N, Lerman J. Development and psychometric evaluation of the pediatric anesthesia emergence delirium scale. Anesthesiology. 2004; 100(5): 1138-45. PubMed

- Watcha MF, Ramirez-Ruiz M, White PF, et al. Perioperative effects of oral ketorolac and acetaminophen in children undergoing bilateral myringotomy. Can J Anaesth. 1992; 39(7):649–54. PubMed

Other References

- Vlassakova BG. Emergence delirium. OpenAnesthesia OA Vodcast. Published 2017. Accessed October 16, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.