Copy link

Craniosynostosis and Craniofacial Dysostosis

Last updated: 03/14/2023

Key Points

- Craniofacial dysostosis syndromes, in which craniosynostosis exists along with multiple other comorbidities, account for approximately 20% of craniosynostosis cases.

- Craniofacial dysostosis syndromes often involve midface, tracheal and spinal anomalies as well as obstructive sleep apnea, all of which can contribute to a challenging airway.

- Upper airway obstruction at induction of anesthesia is common, and bag-mask ventilation is often challenging, but difficult intubation is rare and limited to those patients with cervical spine anomalies.

Introduction

- Craniosynostosis occurs due to the premature fusion of one or more sutures in the skull, which leads to irregular skeletal expansion and a characteristic abnormal head shape.1,2 In 80% of cases, craniosynostosis occurs in isolation with only cranial suture involvement.1

- Craniofacial dysostosis describes syndromic forms of craniosynostosis where cranial suture anomalies are associated with midface skeletal anomalies and various other organ system defects.2 Syndromic craniosynostosis accounts for 20% of cases.1

- Syndromic craniosynostosis affects between 1 in 25,000 and 1 in 100,000 infants.3

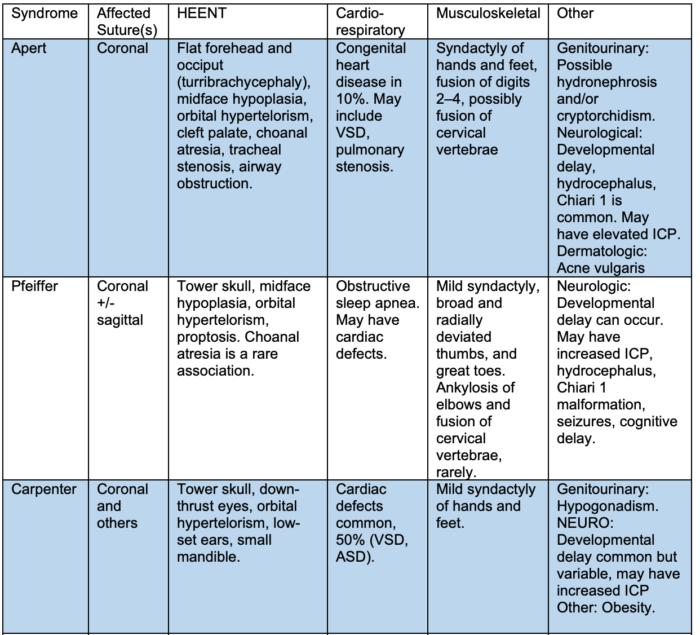

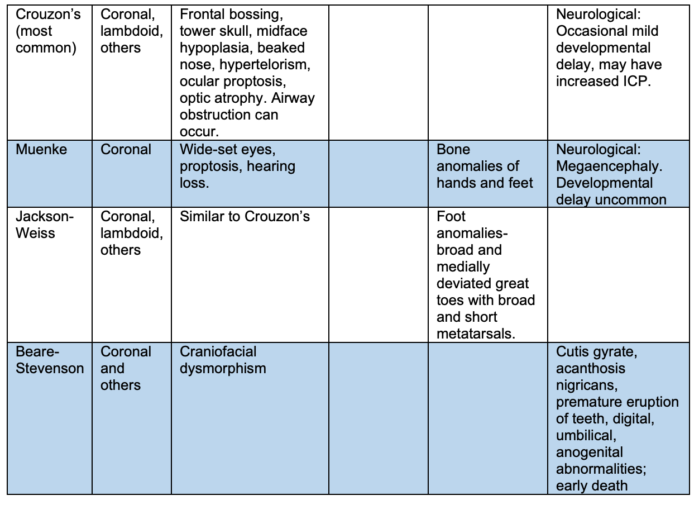

- Craniofacial dysostosis syndromes typically have an identifiable genetic cause.1 Mutations in genes encoding the fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs) are responsible for the most common syndromes, listed in Table 1.

Common Features and Comorbidities

Table 1. Clinical features of FGFR-related craniofacial dysostosis syndromes.1-6 (ICP = intracranial pressure; ASD = atrial septal defect; VSD = ventricular septal defect).

- Craniofacial dysostosis syndromes often involve midface, tracheal and spinal anomalies as well as obstructive sleep apnea, all of which can contribute to a challenging airway.

- Maxillary hypoplasia, proptosis, mandibular prognathia, a high-arched palate, a large tongue in relation to a small oral cavity, small nares, and some degree of choanal stenosis are shared features of some of the most common craniofacial dysostosis syndromes,1-5 as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Top left: Apert Syndrome. Image from Onda N, Chiba S, Moriwaki H, et al. Withdrawal of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Therapy after Malar Advancement and Le Fort II Distraction in a Case of Apert Syndrome with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2015; 2015: 125023. (Open Access) CC BY 3.0; Top right: Crouzon Syndrome. Images from: Anantheswar YN, Venkataramana NK. Pediatric craniofacial surgery for craniosynostosis: Our experience and current concepts: Parts -2. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2009 Jul-Dec; 4(2): 100–107. (Open Access) CC BY-NA-SA 3.0; Bottom: Pfeiffer Syndrom. Image from Singh RK, Verma JS, Srivastava AK, et al. Common primary fibroblastic growth factor receptor-related craniosynostosis syndromes: A pictorial review. J Pediatr Neurosci . 2010 Jan;5(1):72-5. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.66685. (Open Access) CC BY 2.0.

- Craniosynostosis can lead to increased intracranial pressure (ICP), which is most commonly seen in syndromic forms.1 Elevated ICP can occur due to hydrocephalus, chronic airway obstruction, craniocerebral disproportion, or abnormalities in venous drainage of the brain.

- Patients with craniosynostosis typically undergo surgery for cranial vault reconstruction before one year of age.1 Patients with syndromic craniosynostosis frequently require additional general anesthetics for various diagnostic, craniofacial, airway optimization, and neurosurgical procedures.4

Airway Management Considerations

- Many craniosynostosis syndromes present airway problems such as difficult mask ventilation or intubation. Careful preoperative airway assessment and planning is required.1

- Maxillary hypoplasia, mandibular prognathia, a high-arched palate, large tongue, small nares, and choanal stenosis can result in multilevel upper airway obstruction and obstructive sleep apnea.1-5

- In some cases, severe upper airway obstruction necessitates tracheostomy placement early in infancy.

- Vertebral fusions can lead to limited movement of the cervical spine.4

- Tracheal ring abnormalities or cartilaginous sleeves may be present. Patients may also have laryngomalacia and/or tracheobronchomalacia.4

- Perioperative upper airway obstruction is common during induction of anesthesia, with resultant difficult bag-mask ventilation.4 Upper airway obstruction can occasionally occur after emergence from anesthesia as well.

- Mask fit may be problematic due to midface hypoplasia and proptosis.5

- Gently holding the mouth open (rather than closing it) during mask ventilation allows for air movement through the oral cavity while minimizing obstruction due to the tongue.5

- An appropriately sized oral and/or nasopharyngeal airway is often useful. Spraying the mouth with a topical anesthetic prior to induction will facilitate the placement of an oral airway at lighter depths of anesthesia during mask induction.5

- A supraglottic airway is effective in relieving upper airway obstruction.4

- Intubation is usually not as difficult, with some notable exceptions.4

- Intubation may be difficult if there is a problem with neck mobility.5

- Video laryngoscopy or fiberoptic techniques should be considered in patients with cervical spine concerns.

- Tracheal anomalies may necessitate the use of a smaller endotracheal tube.5

- In patients who have had prior frontofacial distraction surgery, difficult laryngoscopy may occur due to an altered maxilla-mandibular relationship and a reduction in temporomandibular joint movement.4

References

- Thomas K, Hughes C, Johnson D, Das S. Anesthesia for surgery related to craniosynostosis: a review. Part 1. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22(11):1033-41. PubMed

- Posnick JC, Tiwana PS, Ruiz RL. Craniofacial dysostosis syndromes: evaluation and staged reconstructive approach. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2010;18(2):109-28. PubMed

- Forrest CR, Hopper RA. Craniofacial syndromes and surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(1):86e-109e. PubMed

- Venkat Raman V, de Beer D. Perioperative airway complications in infants and children with Crouzon and Pfeiffer syndromes: A single-center experience. Pediatr Anaesth. 2021; 31: 1316– 24. PubMed

- Nargozian C. The airway in patients with craniofacial abnormalities. Pediatr Anesth. 2004; 14: 53- 9. PubMed

- Stricker PA, Fiadjoe JE. Anesthesia for craniofacial surgery in infants. Anesthesiol Clin. 2014; 32(1): 215-35. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.