Copy link

COVID-19

Last updated: 05/24/2024

Key Points

- Perioperative management of patients with COVID-19 should be guided by recent research evidence.

- The Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF) COVID-19 Anesthesia Resource Center and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) In the Spotlight COVID-19 website are good resources for evolving guidelines.

- Decisions about the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care of patients with COVID-19 include considerations for patient safety, personnel safety, and local community transmission rates.

Introduction

- The COVID-19 pandemic emphasized the importance of prioritizing patient and healthcare personnel safety to prevent, detect, and mitigate the spread of disease. It also demonstrated the need for improved communication and collaboration to adapt guidelines to local resources and emerging data.

- Data collection through individual case reports, institutional experiences, and international sharing through online podcasts, open-access preprints, and publications contribute to the development of joint statements and guidelines from multiple organizations.

- The APSF created a Novel Coronavirus Anesthesia Resource Center to share the latest research, guides, statements, and information during an evolving situation, and the ASA has many statements and recommendations on COVID-19.

- Safety priorities include preoperative patient selection and perioperative practices to prevent transmission.

Preoperative Considerations

Screening and Testing1,2

- All patients should be screened for symptoms and exposure to COVID-19, including unexplained fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, rhinorrhea, and/or new loss of taste or smell, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or close contact with someone diagnosed with COVID-19 in the past ten days.

- Patients with active COVID-19 have higher perioperative morbidity and mortality, especially patients with advanced age, higher ASA physical status, cardiac risk, and immunocompromised status.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for SARS-CoV2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is 95% sensitive, so there can be false negatives. Patients may test positive for up to three months after infection despite being noninfectious. Repeat testing for patients with a positive test within 90 days of symptom onset is not necessary.

- Viral transmission can occur from three days before symptom onset to ten days afterwards in healthy adults with mild to moderate COVID-19. Still, replication-competent virus has been identified beyond 20 days in moderately to severely immunocompromised patients. Use time- and symptom-based strategies to determine infectious risk.3

- Consider whether preoperative COVID-19 testing will mitigate risk to the patient, risk to other patients, or risk to healthcare providers. Use community levels of COVID-19 and community transmission, in addition to local resources and policies, to guide decision-making.

- Routine universal testing of asymptomatic patients is not currently recommended.

Patient Classification4

- Classify patients with COVID-19 by severity of illness per NIH Guidelines:

- Asymptomatic or presymptomatic infection: Individuals who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 using a virologic test (i.e., a nucleic acid amplification test [NAAT] or an antigen test) but have no symptoms consistent with COVID-19.

- Mild illness: Individuals who have any of the various signs and symptoms of COVID-19 (e.g., fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of taste and smell) but do not have shortness of breath, dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging.

- Moderate illness: Individuals who show evidence of lower respiratory disease during clinical assessment or imaging and have an oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2) ≥ 94% on room air at sea level.

- Severe illness: Individuals who have an SpO2 < 94% on room air at sea level, a ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2 / FiO2) < 300 mmHg, a respiratory rate > 30 breaths/min, or lung infiltrates > 50%

- Critical illness: Individuals who have respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiple organ dysfunction

Delaying or Proceeding with Surgery3,5,6

- In 2020, recommendations were that patients with mild illness should delay surgery four weeks, patients with moderate illness treated at home as an outpatient should delay six weeks, and patients with severe illness that required hospitalization, are immunocompromised, or have diabetes, should wait 8-10 weeks after recovery before undergoing surgery. Patients with critical illness requiring an ICU stay should wait 12 weeks.

- Updated guidelines recommend delaying elective surgery within two weeks of a SARS-CoV-2 infection to assess symptom severity and mitigate transmission risk. Symptomatic patients should be rescheduled. The anesthesiologist, surgeon/proceduralist, and the patient should share decision-making to schedule low-risk patients between 2 and 7 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection, weighing the risk of proceeding with the risk of delay. Further delays beyond seven weeks for ongoing symptoms should be considered.

- Additional preoperative workup may be necessary for patients with symptoms of long COVID,7 including fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, headaches, diarrhea, and joint pain. Additional tests, such as an EKG, echocardiogram, labs, or cardiac evaluation, should be considered.

- If proceeding with surgery in a symptomatic patient, clinicians should redesign the workflow to optimize the best pathway of patient transport and location of the preoperative holding area and postoperative recovery room to limit exposure and transmission. Proper availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) should be ensured for all team members involved in the patient’s care. Checklist implementation, limiting staff members, and removing unnecessary equipment and materials from the operating room should be considered.

Preoperative Planning for Anesthesia Type & Surgical Case Considerations8,9

- Monitored anesthesia care (MAC): An open airway poses a risk for viral particle transmission and the potential for an urgent conversion to general anesthesia. The patient’s need for supplemental oxygen should be balanced with the increased potential for aerosolization of respiratory secretions, especially with higher flow levels.

- General anesthesia: Cuffed endotracheal tubes create a closed airway circuit to limit transmission. Laryngeal mask airways may decrease coughing and be safe at lower pressures but risk operating room contamination and air leakage at higher pressures.

- Regional anesthesia: There are no contraindications to neuraxial or peripheral nerve blocks in patients with COVID-19. Regional anesthesia may reduce the need for aerosol-generating procedures with general anesthesia.

- Airway cases, including bronchoscopy, endoscopy, and ENT surgeries, can increase the risk of aerosolized airway secretions through coughing and sneezing. When endotracheal tubes aren’t feasible, procedural oxygen masks with openings can minimize particle dispersion. Patients presenting with labored breathing or screaming may pose additional risks.

Intraoperative Considerations

Negative Pressure Rooms10

- When possible, use negative-pressure operating rooms to prevent transmission to other operating rooms.

- Operating rooms should have air filtration systems with a minimum efficiency reporting value of 14.

- Alternative options include turning off positive pressure, maximizing air change rates, or using portable HEPA filters.

Hand Hygiene & Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)9

- Wash hands before donning and doffing PPE

- Proper donning and doffing of PPE for airborne, droplet, and contact precautions should be ensured during intubation and extubation to minimize the risk of self-contamination.

- PPE includes fluid-resistant gowns, gloves, face shields, goggles, and N95 or higher respirators. Double-gloving should be considered to remove contamination after intubation.

Intubation and Extubation9

- Limiting the number of team members present during intubation and extubation should be considered.

- The plan and expectations should be discussed with members present, especially if deciding to wait a period for air cycle changes per hour in the OR (e.g., no opening doors for 15 minutes after intubation or extubation).

- The plan for unanticipated difficult airway and availability of equipment and materials if necessary should be ensured.

- Using the most experienced anesthesia clinician to perform a rapid-sequence intubation with indirect laryngoscopy can avoid manual ventilation and minimize the duration of exposure to aerosols.

- Awake fiberoptic intubations can increase the risk of aerosolization during topicalization of local anesthetics.

- Laryngeal mask airways risk inadequate seal and escape of viral particles.

- After intubation, personnel should dispose of outer gloves and seal contaminated airway equipment for removal. Hand hygiene and the potential for self-contamination during doffing should be remembered.

- High-quality viral filters rated should be used to remove at least 99.97% of airborne particles 0.3 microns or greater placed between the ETT and circuit/reservoir bag.

- Some institutions have trialed intubation boxes or smoke evacuators to decrease viral particle exposure during airway manipulation.

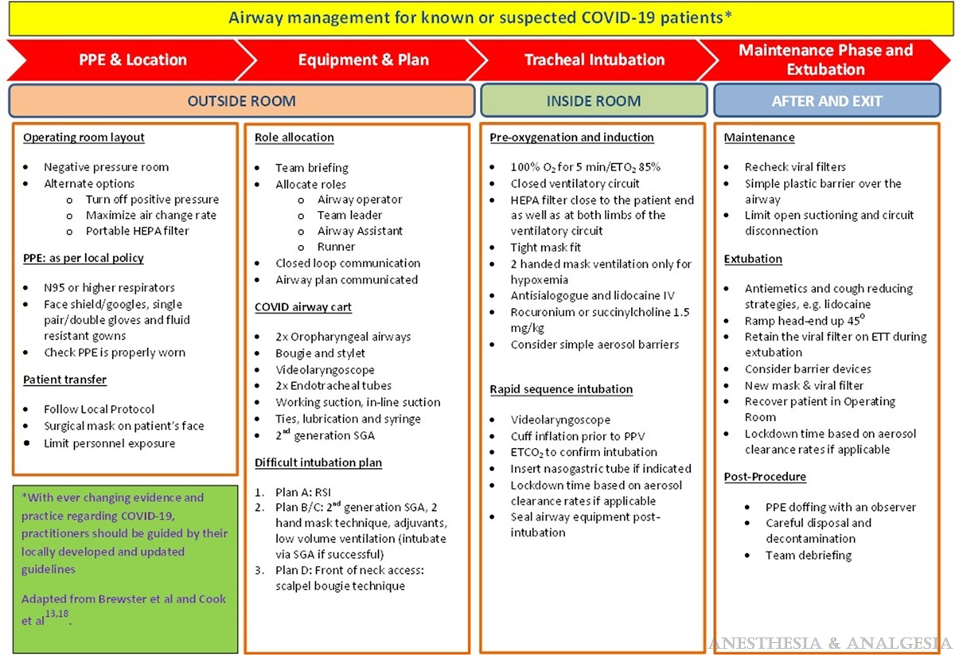

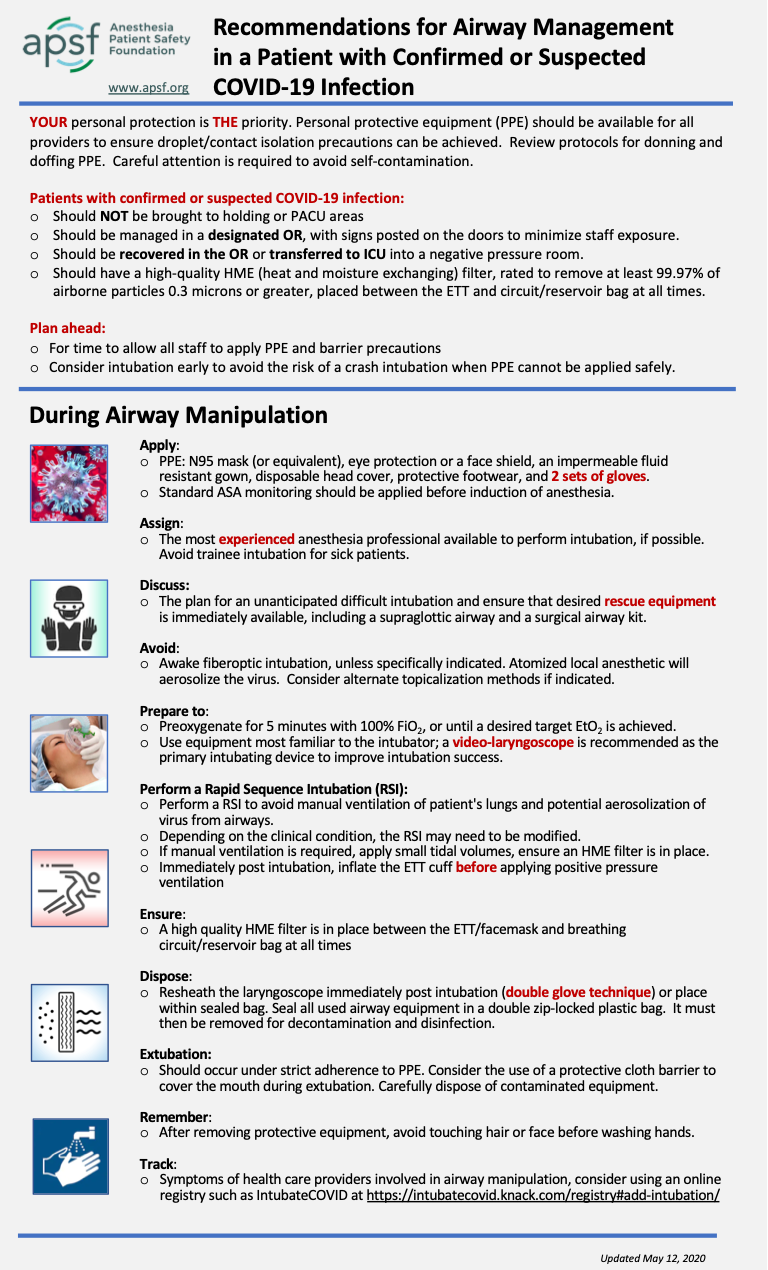

- Figures 1 and 2 outline the workflow for airway management for COVID-19 patients.

Figure 1. Airway Management for Known or Suspected COVID-19 patients. Used with permission from Thiruvenkatarajan V, et al. Airway Management in the Operating Room and Interventional Suites in Known or Suspected COVID-19 Adult Patients: A Practical Review. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(3):677-89.

Figure 2. Recommendations for airway management in a patient with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Accessed May 8, 2024. Link

Postoperative Considerations

- Patients should be recovered in an airborne infection isolation room (AIIR). Criteria for AIIR include: at least 12 air exchanges per hour, inability to inadvertently change ventilation modes from negative pressure to positive pressure, tightly sealed room with self-closing doors, permanent indicator of airflow visible when room is occupied, and 90% efficiency filtration system.10

- Terminal cleaning should be performed after an adequate number of air changes.10

References

- ASA and APSF statement on perioperative testing for the COVID-19 virus. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. December 8, 2020. Updated June 15, 2022. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- ASA and APSF Updated statement on perioperative testing for SARS-CoV-2 in the asymptomatic patient. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. December 21, 2022. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- Bechtel, A. Episode #25 Keeping patients safe after COVID-19 infection. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Podcasts. December 27, 2020. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health. Updated February 29, 2024. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- ASA and APSF Joint statement on elective surgery/procedures and anesthesia for patients after COVID-19 infection. March 9, 2021. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- Zucco L, Levy N, Ketchandji D, Aziz M, Ramachandran SK. An update on the perioperative considerations for COVID-19 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Anesthesia Patients Safety Foundation Newsletter. June 2020. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- Long COVID. Centers for Disease Control.Updated March 14, 2024. Accessed May 8, 2024. Link

- Bechtel, A. Episode #10 Covid-19 and Anesthesia Clinical Care FAQ. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Podcasts. September 8, 2020. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- Uppal V, Sondekoppam RV, Lobo CA, Kolli S, Kalagara HKP. Practice recommendation on neuraxial anesthesia and peripheral nerve blocks during the COVID-19 pandemic. ASRA News. 2020, Mar 27;45. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- Bechtel, A. Episode #18 Coronavirus Resources: OR Ventilation. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation Podcasts. November 3, 2020. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

Other References

- Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Anesthesia Resource Center. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- ASA’s Statements and Recommendations on COVID-19. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Accessed April 30, 2024. Link

- 3. Yu, CJ. Anesthesiologist Trials Taiwanese Intubating Box [Video]. YouTube. Link. Published April 2, 2020. Accessed May 8, 2024. Yu, CJ. Anesthesiologist Trials Taiwanese Intubating Box [Video]. YouTube. Published April 2, 2020. Accessed May 8, 2024. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.