Copy link

Congenital Lobar Emphysema

Last updated: 04/22/2025

Key Points

- Congenital lobar emphysema (CLE) is a rare developmental anomaly of the lower respiratory tract that is characterized by hyperinflation of one or more pulmonary lobes. It is often caused by obstruction to a portion of the developing airway, which causes air-trapping and subsequent respiratory distress in infants.

- Definitive treatment involves resection of the affected lobe, either by open thoracotomy or minimally invasive techniques.

- Positive pressure ventilation and nitrous oxide should be avoided to prevent further hyperinflation of the lung and respiratory compromise.

Pathophysiology

- CLE is a rare developmental anomaly of the lower respiratory tract characterized by hyperinflation of one or more pulmonary lobes. It is often caused by obstruction to a portion of the developing airway, which causes air trapping and subsequent respiratory distress in infants.1-3

- CLE can cause the overdissension of one or more lobes of the lung, leading to compression of remaining lung tissue and herniation of the affected lobe across the anterior mediastinum into the opposite chest. This causes contralateral mediastinal shift, contralateral lung hypoplasia, and secondary hypoxia. Impaired venous return and hypotension may also result.

- The emphysematous low-compliance lobe communicates with a bronchial tree, leading to the development of an obstructive “ball valve” effect at the bronchial level, where air can enter the lesion but not escape.

- The left upper lobe is the most commonly affected lobe, followed by the right middle lobe and the right upper lobe. Bilateral pathology is less common but has been reported.

- The incidence of CLE is 1 in 20,000-30,000 with a 3:1 male predisposition.

- CLE is typically associated with a normal pulmonary blood supply.

- Alveoli are enlarged and can be increased in number, but they do not exhibit true emphysematous changes like the destruction of the alveolar walls, as seen in acquired emphysema.1

Etiology

- In half of patients with CLE, the underlying etiology is idiopathic.3 Other frequently identified causes of CLE are intrinsic or extrinsic obstruction of the airway that leads to air trapping.

- Intrinsic obstruction is more common. This includes intramural lesions resulting from bronchial cartilage deficient in quantity or quality and subsequent wall collapse.

- Intraluminal obstruction causes obstruction through a ball-valve type mechanism. This can be due to meconium, mucus plugs, granulomas, or redundant mucosal folds.1-3

- Extrinsic compression can be caused by lesions outside the bronchial wall, usually from a vascular or cardiac abnormality. Examples include patent ductus arteriosus, tetralogy of Fallot, and vascular rings. Other types of extrinsic obstruction on the bronchus include intrathoracic masses such as enlarged lymph nodes, bronchogenic cysts, or teratomas.1-3

Clinical Presentation

- Many infants are symptomatic at birth (33%) or within the first month of life (50%). Presentation is uncommon after 6 months.1-3

- Patients with CLE usually present with progressive respiratory distress, which can be rapid in onset or gradual, depending on the size of the affected lobe and its effect on surrounding tissues.

- Specific symptoms include tachypnea, increased work of breathing, wheezing, cyanosis, and frequent respiratory infections.1-3

- Physical examination reveals respiratory distress, often with wheezing, decreased breath sounds over the involved lobe, and displacement of the cardiac impulse if there is mediastinal shift.1-3

- CLE is also seen along with other congenital anomalies, and 14% of cases have an associated cardiac anomaly, with patent ductus arteriosus and ventricular septal defects being the most common.1

Diagnosis

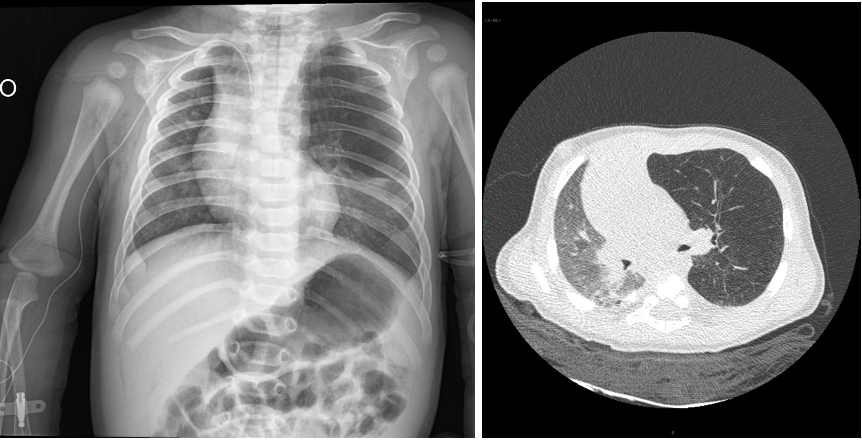

- A diagnosis of CLE can be made from chest radiograph findings of distention of the affected lobe with contralateral mediastinal shift, atelectasis of the contralateral lung, and an ipsilateral flattened diaphragm (Figure 1). CLE is often confused with pneumothorax but can be differentiated from it by the presence of vascular markings.

Figure 1. Chest x-ray and computed tomography of a 4-month-old infant showing hyperinflation and poor vascularization of the left upper lobe with contralateral mediastinal shift. Case courtesy of Domenico Nicoletti, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 37234.

- Computed tomography imaging, echocardiography, or bronchoscopy can help further define the anatomy and elucidate the cause of bronchial obstruction.

- Ventilation/perfusion studies show decreased ventilation and perfusion in the affected lobe.1

- The definitive diagnosis is made by a pathology exam after surgical resection.

Treatment

- The definitive treatment for symptomatic CLE is early resection of the affected lobe, either by open thoracotomy or minimally invasive thoracoscopic techniques.1

- A thoracoscopic approach is often the technique of choice as it carries less risk of complications but is technically more challenging for upper segments. Hemithorax insufflation with low pressures can aid in lung collapse.4

- If history, symptoms, or chest radiography findings suggest the cause of overinflation is a mucus plug or foreign body, bronchoscopy can be curative.1

- Asymptomatic patients are candidates for conservative management, given that this anomaly does not increase the risk of infection or malignancy.

- CLE is often considered a surgical emergency in rapidly deteriorating patients.

Anesthetic Considerations

- Preoperative evaluation should focus on cardiopulmonary stability. It is crucial to determine the extent of airway compression and physiologic compromise, as impairment may worsen with anesthesia induction.

- Inhalational induction with spontaneous ventilation or intravenous (IV) induction is appropriate. Surgeons should be present during induction to open the chest in case the lobe expands. When CLE is causing severe, critical respiratory failure, opening the chest allows the oversized lobe to herniate through the incision, relieving pressure on functioning lobes.4

- Aggressive high-pressure ventilation should be avoided during the procedure.

- A crying infant that is resisting induction can increase the amount of trapped gas, and positive pressure ventilation can also worsen emphysema. Therefore, a smooth inhaled induction with sevoflurane and oxygen should be performed with minimal use of positive pressure ventilation. Nitrous oxide should be avoided as it can cause expansion of the enlarged regions.4,5

- The airway should be secured with an endotracheal tube. If one-lung ventilation is planned, options include either an endobronchial intubation or the placement of a bronchial blocker. Please see the OA summary on one-lung ventilation in children for more details. Link

- Standard American Society of Anesthesiologists monitors should be used and an arterial line is commonly inserted. Given the potential for blood loss, adequate vascular access should be secured. Significant blood loss occurs infrequently.

- Total IV anesthesia or a combination of gas or IV anesthetics may be used. Isoflurane is the preferred volatile anesthetic due to its less attenuation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction.

- Preincision epidural should be considered in open thoracotomy cases to assist with pain control and early extubation after surgery.

- Ventilation will likely improve after the aberrant lung segment is removed. At the end of the case, many patients can be extubated.

References

- Kravitz RM. Congenital malformations of the lung. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1994; 41:453-72. PubMed

- Oermann CM. Congenital lobar emphysema. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2025. Link

- Mukhtar, S, Sharma, S, Trovela DAV. Congenital lobar emphysema. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island, FL. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Link

- Taylor JS, Wall J, Giustini AJ, Claure RE, Golianu, B. Pediatric General Surgery. In: Jaffe, RA. Anesthesiologist’s Manual of Surgical Procedures, Sixth Edition. Philadelphia; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2020; 1443-1448.

- Hammer, GB. Anesthesia for Thoracic Surgery. In: Davis PJ, Cladis FP. Smith’s Anesthesia for Infants and Children, Tenth Edition. Philadelphia; Elsevier Inc, 2022; 866-884.

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.