Copy link

Chronic Subdural Hematoma

Last updated: 05/23/2023

Key Points

- Chronic subdural hematoma (SDH) results from tearing of bridging veins in the subdural space that becomes encapsulated in neomembranes and forms a hygroma over the course of weeks to months.

- Normal SDH absorption from counter pressure from brain parenchyma is often absent in chronic SDH.

- Patients with chronic SDHs are more likely to present with nonspecific symptoms such as headache, seizures, behavioral changes, focal deficits, hemiparesis, etc.

- The treatment of chronic SDH depends on the etiology and clinical context.

Etiology

- SDH is a type of intracranial hemorrhage characterized by bleeding that occurs between the dural and arachnoid membranes that surround the brain.1,2

- SDHs can be classified into several subtypes based on:2

- Time course: acute, subacute, acute on chronic, and chronic

- Etiology: traumatic, spontaneous, and other pathologies

- Special considerations: anticoagulation-induced, bilateral, recurrent, etc.

- Chronic SDH can result from minor head trauma, especially in patients with age-related brain atrophy or on anticoagulation.2

- Lowering of intracranial pressures (ICP) can also lead to chronic SDH.

- Decreased ICP may result from a cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) leak following lumbar puncture, ventriculostomy, shunt placement, or other neurosurgical procedure.1

- The decrease in ICP causes the brain to depress in the skull leading to engorgement and stretching of the bridging veins.2

Pathophysiology

- Minor trauma leads to damage of venous structures and a collection of small amounts of blood in the subdural space.

- Normal absorption of SDH is reliant upon counter pressure from brain tissue and the lack of potential subdural space.

- The minor inciting events for chronic SDH typically cause little brain swelling.

- The patients at risk for chronic SDH often have increased subdural space from aggressive shunting, atrophy, or alcoholism.2

- Continued bleeding may be due to the formation of neomembranes around the hematoma.2

- Part of this membrane is highly vascularized and may lead to repeat bleeding.

- Another part of the membrane secretes antithrombotic and fibrinolytic enzymes.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

- Patients with chronic SDH are more likely to present with nonfocal symptoms such as headache, light-headedness, seizures, behavioral changes, cognitive impairment, somnolence, gait disturbances, memory problems, etc.1-3

- Chronic SDH is as a reversible cause of dementia.3

- A noncontrast head computed tomography is often used to diagnose chronic SDH. It appears as a crescent-shaped mass, and is often more hypodense than an acute SDH.3

Treatment Options

- Like acute SDH, the treatment of chronic SDH includes:1,2

- Ensuring a patent airway, adequate oxygenation, and ventilation

- Maintaining stable hemodynamics and avoiding hypo- or hypertension

- Performing a detailed neurological examination to determine the severity of neurological deficits and provide a baseline to assess for clinical deterioration.

- Avoiding elevations in ICP by raising the head of the bed and ensuring venous drainage

- Reversing anticoagulation, if necessary

- Administering seizure prophylaxis

- Neurosurgical consultation for surgical decompression

- Surgical decompression is a treatment option for chronic SDH.

- Most surgeons agree that many chronic SDHs require surgery because the body lacks the natural ability to reabsorb the blood.2

- Surgery is commonly required due to the tendency of the bleeding to increase overtime.2

- Indications for surgical evacuation include clot thickness greater than 10 mm or midline shift greater than 5 mm on brain scans.2

- All symptomatic lesions should be considered for surgical management.2

- Multiple surgical techniques have been used for surgical evacuation and any of them can be augmented by the placement of a subdural drain.1,2

- Open craniotomy

- Burr-hole craniotomy

- Twist-drill craniostomy with drainage catheter, which can be performed at the bedside in the intensive care unit.

- Embolization of the middle meningeal artery (MMA)

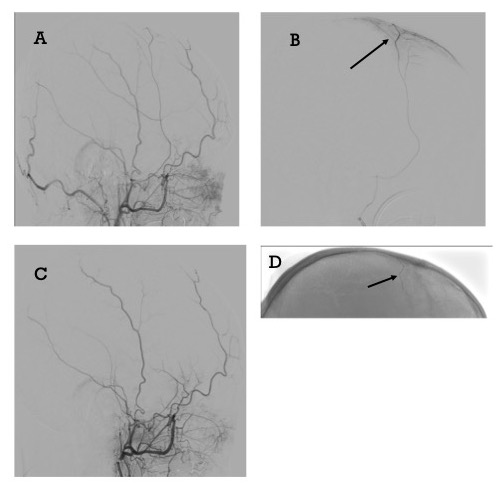

- MMA embolization may be used as adjunctive therapy to prevent recurrence after the mass effect is reduced4 (Figure 1).

- MMA embolization reduces recurrence rates by preventing microbleeding episodes from immature neovessels of the membranes surrounding the chronic SDH.4

Figure 1. CT angiography of middle meningeal artery (MMA) and skull x-ray postembolization. A. Left external carotid artery (ECA) angiography pre-embolization, B. Left MMA angiography pre-embolization arrow indicates MMA, C. Left ECA angiography post MMA embolization, D. X-ray of skull with onyx cast in left MMA, arrow indicates MMA.

References

- McBride W. Subdural hematoma in adults: Etiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. In: Post T (ed). UpToDate; 2023.

- Huang KT, Bi WL, Abd-El-Barr M, et al. The neurocritical and neurosurgical care of subdural hematomas. Neurocritical Care. 2016; 24: 294-307. PubMed

- Sahyouni, R, Goshtasbi K, Mahmoodi A, et. al. Chronic subdural hematoma: A historical and clinical perspective. World Neurosurg. 2017; 108:948-53. PubMed

- Haldrup M, Ketharanathan B, Debrabant B, et al. Embolization of the middle meningeal artery in patients with chronic subdural hematoma- a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acts Neurochir (Wien). 2020; 162:777-84. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.