Copy link

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Pregnancy

Last updated: 12/19/2024

Key Points

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a pregnant patient differs from that of a nonpregnant patient in four important ways:

- Manual left uterine displacement should be performed to relieve aortocaval compression if the uterus is at or above the umbilicus.1,2

- Perimortem cesarean delivery should be performed by 4-5 minutes if the return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is not achieved; it should be performed at the site of the arrest.1

- Since pregnant patients are more prone to hypoxemia, airway management and adequate oxygenation should be prioritized during resuscitation.2,4

- Vascular access should be obtained above the diaphragm.1,2

Prevalence

- Data from 1998-2011 reports 1 in 12,000 admissions for delivery experience cardiac arrest.5

- Of those women who do experience cardiac arrest during pregnancy, 54% survive hospital discharge,2,3 a much greater percentage compared to the nonpregnant cohort.

- Throughout all of pregnancy, cardiac arrest incidence ranges from 1:20,000 to 1:40,000 in industrialized countries.2,6

Differences from the Nonparturient

Basic life support (BLS) and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) apply to the parturient. However, the physiologic changes of pregnancy require some modifications during resuscitation. In contrast, medications, dosages, and cardioversion/defibrillation energies are unchanged.2,3,4

Manual Left Uterine Displacement (LUD)

- LUD relieves aortocaval compression.1-3 It improves preload and cardiac output, with the goal of end-organ perfusion and circulation of administered medications.

- LUD should be performed in any pregnant patient with a visible/palpable gravid uterus at or above the umbilicus.1,2

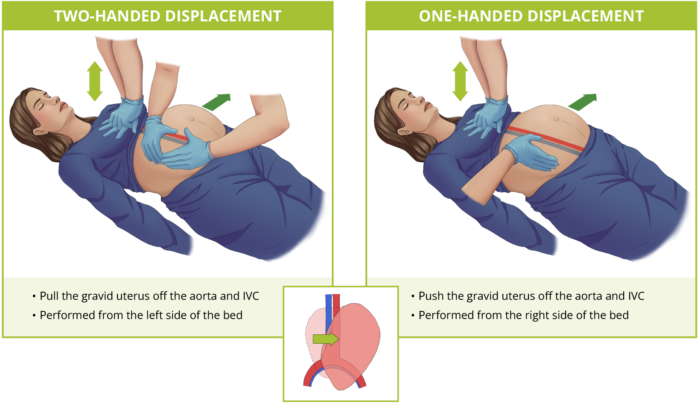

- LUD is best achieved by a designated provider using one or two hands to lift the uterus manually and to the left1 (Figure 1).

- The old adage of 15–30-degree tilt is NOT recommended as it can lessen the effectiveness of chest compressions.1,3

- A solo provider can kneel on the patient’s left and place bent knees under the back.3

Figure 1. Two-handed and one-handed uterine displacement while performing chest compressions in a pregnant patient. Abbreviation: IVC = inferior vena cava. Redrawn from cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation published in Amboss.com

Perimortem Cesarean Delivery (PMCD) or Resuscitative Hysterotomy

- If ROSC is not achieved by 4 min from the onset of arrest, skin incision should be made for PMCD with the goal of delivering the infant in 5 min. To achieve this time goal, preparation for cesarean delivery begins almost immediately after identification of maternal arrest.1,2 PMCD can be initiated with only a scalpel.4

- PMCD improves maternal and fetal outcomes by relieving aortocaval compression, decreasing O2 demand, and improving pulmonary mechanics and the quality of chest compressions.2

- Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be continued throughout and following the delivery of the fetus.2

- PMCD should be performed at the site of arrest.2 Delays occur when attempting to move the patient to the surgical suite. The patient may be transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for more specialized care after PMCD.

- If the fetal station allows, operative vaginal delivery can also be considered.2

- If ROSC is achieved prior to PMCD (i.e., within 4-5 min), external fetal monitoring should be initiated.3

- PMCD can be considered earlier than 5 minutes for prolonged unwitnessed maternal arrest (i.e., low likelihood of maternal survival a priori) or high likelihood of maternal aortocaval compression.4

- PMCD can be delayed longer for witnessed cardiac arrest and known reversible causes of cardiac arrest.4

Airway

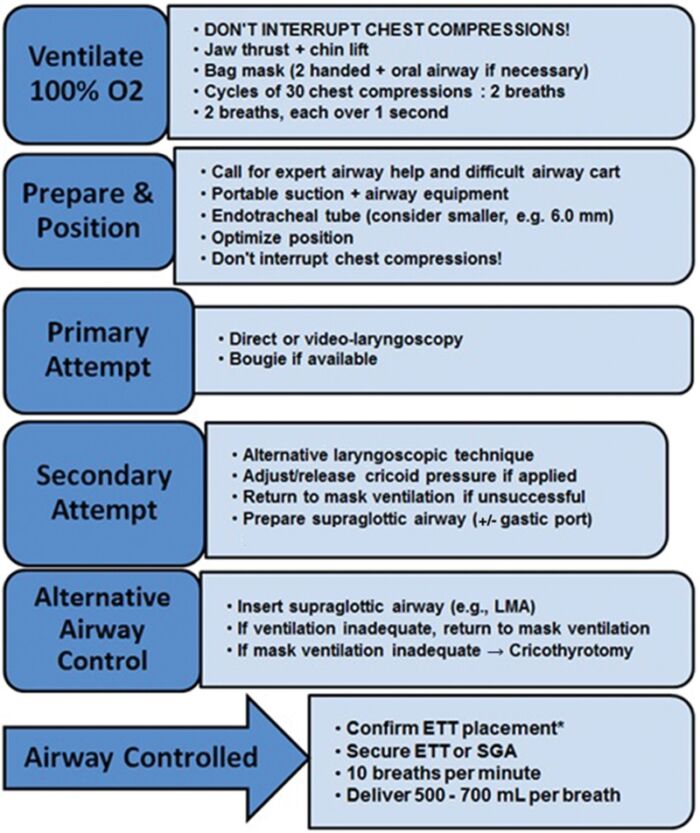

- Since pregnant patients are more prone to hypoxemia, airway management and adequate oxygenation should be prioritized during resuscitation2,4 (Figure 2).

- A difficult airway should be anticipated, and the most experienced provider should perform endotracheal intubation.2 The incidence of difficult airway in pregnancy is 1:400, whereas, in the general population, it is less than 1:22,000.4,7

- Video laryngoscopy should be considered for the first intubation attempt.

- A smaller diameter endotracheal tube (6.0 to 6.5) should be used due to airway swelling.2

- Nasal intubation should be avoided due to the increased risk of damage to friable tissue with subsequent bleeding.2

- A supraglottic airway should be used after two failed intubation attempts by an experienced provider.2

- Endotracheal intubation should be confirmed with end-tidal CO2 monitoring if available.

Figure 2. An example of an airway algorithm for maternal cardiac arrest in pregnancy. Used with permission from Lipman S et al. The SOAP consensus statement on the management of cardiac arrest in pregnancy. Anesth Analg. 2014.2

BLS/ACLS Component Considerations

Compressions/Breathing

- The compressor’s hands should be placed in the usual midsternal position, aiming for a depth of 5 cm and 100 compressions per minute.2

- If an advanced airway is present → 10 breaths/min with 100 compressions/min2

- For an unsecured airway or if no advanced airway is present → 30 compressions/2 breaths2

- Previous instructions to move the hands cephalad to account for displacement of mediastinum by abdominal contents are not beneficial and should not be done.1,3

Defibrillation/Cardioversion

- Defibrillation and cardioversion are safe in all stages of pregnancy at the same energies as nonpregnant counterparts.1

- They should not be delayed for removing internal or external fetal monitors.1,2 However, if additional help is available, consider removing them.

Other Drugs

- If the patient is receiving magnesium therapy, it should be stopped immediately, and the administration of calcium chloride or calcium gluconate should be considered.1,2

Additional Modalities

- Adjuncts such as intra-aortic balloon pump, left ventricular assist devices, cardiopulmonary bypass, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation have all been used successfully in the parturient.1

Fetal Monitoring

- Because of potential interference with maternal resuscitation, fetal monitoring should not be performed during cardiac arrest in pregnancy.

Postarrest Care

- Postarrest hypothermia can be considered for similar populations as adult nonpregnant populations. Still, the fetal effects remain unknown.2 The concerns of hypothermia include worsening of maternal coagulopathy and fetal bradycardia.2

Pregnancy-Specific Causes of Arrest

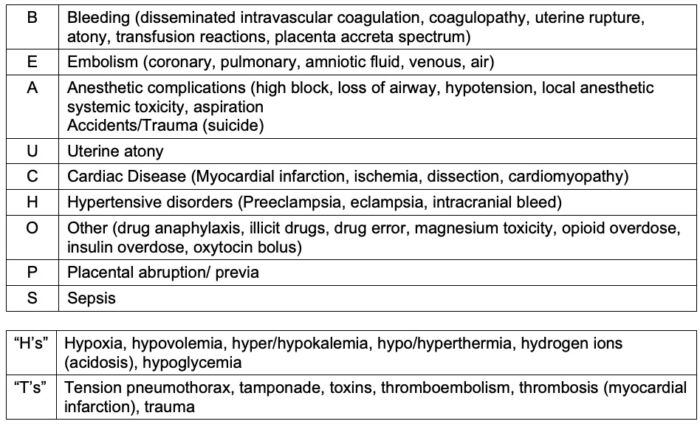

The American Heart Association recommends a pneumonic of BEAU-CHOPS in addition to the “H’s & T’s” to remember potential causes of cardiac arrest in the parturient2 (Table 1).

Table 1. BEAU_CHOPS pneumonic for causes of maternal cardiac arrest in pregnancy.2

Checklist for Key Tasks during CPR in Pregnancy

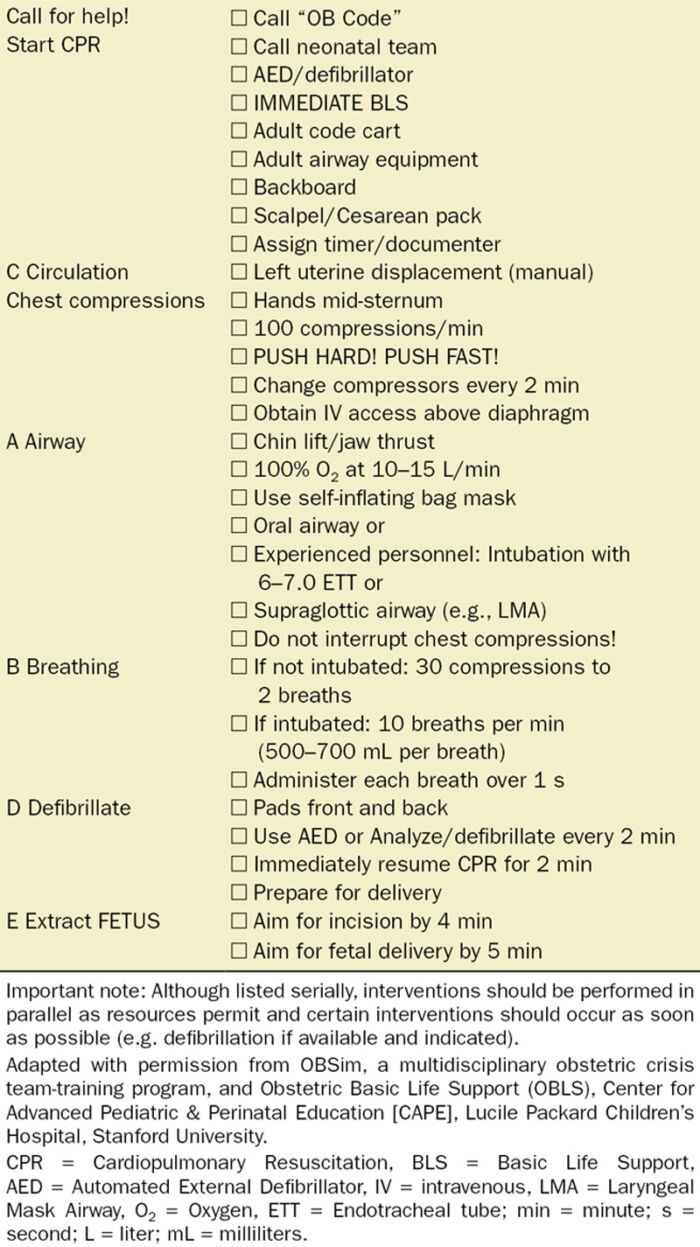

- A checklist of key tasks during CPR in pregnancy is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Checklist of key tasks during CPR in pregnancy. Used with permission from Lipman S et al. The SOAP consensus statement on the management of cardiac arrest in pregnancy. Anesth Analg. 2014.2

References

- Bauchat, J and Van de Velde, M. Nonobstetric surgery during pregnancy. In: Chestnut, D; et al. Chestnut’s Obstetric Anesthesia Principles and Practice 6th Edition. Philadelphia; Elsevier; 2020: 386.

- Lipman S, Cohen S, Einav S, et al. The Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology consensus statement on the management of cardiac arrest in pregnancy. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(5):1003-16. PubMed

- Jeejeebhoy FM, Zelop CM, Lipman S, et al. Cardiac Arrest in Pregnancy: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(18):1747-73. PubMed

- Helviz Y, Einav S. Maternal cardiac arrest. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019;32(3):298-306. PubMed

- Mhyre JM, Tsen LC, Einav S, Kuklina EV, Leffert LR, Bateman BT. Cardiac arrest during hospitalization for delivery in the United States, 1998-2011. Anesthesiology. 2014; 120(4):810-8. PubMed

- Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving mothers' lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The eighth report of the confidential inquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG. 2011;118 Suppl 1:1-203. PubMed

- Pollard R, Wagner M, Grichnik K, Clyne BC, Habib AS. Prevalence of difficult intubation and failed intubation in a diverse obstetric community-based population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(12):2167-71. PubMed

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.