Copy link

Bronchial Asthma

Last updated: 09/10/2024

Key Points

- Bronchial asthma is a disease that involves airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness, specific respiratory symptoms, and obstructive expiratory airflow.

- Asthma affects individuals of all ages globally. Within the United States, there is a higher prevalence in impoverished areas.

- The pathophysiology of allergic asthma involves an IgE-antibody-mediated response. Nonallergic asthma does not involve this pathway and is not triggered by allergens.

- Symptom frequency indicates the severity of the disease and the level of control. Treatment is based on these factors and includes pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.

Introduction

- The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) defines asthma as “a heterogenous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation and a history of respiratory symptoms, such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough, that vary over time and in intensity, together with variable expiratory airflow limitation.”1

- On spirometry: FEV1/FVC ratio reduces to less than 0.7, consistent with an obstructive pattern. The lower the ratio, the more severe the disease.

- This pattern demonstrates reversibility and responsiveness with bronchodilator treatment. However, this can be lacking in patients with irreversible obstruction secondary to chronic inflammation and scarring.

- Environmental triggers, such as tobacco smoke, allergens, airway irritants (dust mites, cleaning product vapors, fragrances), viral respiratory infections, exercise, acid reflux, changes in weather, etc., may cause exacerbation of symptoms.2

- Hyperresponsiveness (easily triggered and exaggerated bronchoconstriction) occurs in response to stimuli.

- Hyperresponsiveness can be tested using a bronchoprovocation test (for example, methacholine challenge test).

Phenotypes

- Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, and different phenotypes exist, making the assessment of prevalence more complex.1

- Allergic asthma is the most common phenotype. It often commences in childhood and is associated with a past or family history of allergic diseases such as eczema, allergic rhinitis, or food allergies. Sputum examination typically reveals eosinophilic airway inflammation. These patients usually respond well to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).

- Nonallergic asthma: These patients with asthma do not have any associated allergic diseases. Sputum examination reveals neutrophils, eosinophils, or only a few inflammatory cells. These patients demonstrate a lesser short-term response to ICS.

- Exercise-induced asthma: Some patients develop asthma symptoms in response to exercise.

- Cough variant asthma: In some asthma patients, cough may be the only asthma symptom.

- Asthma in obese patients: Some obese patients with asthma have prominent respiratory symptoms and minor eosinophilic inflammation.

- Occupational asthma: Some patients develop asthma after exposure to allergens at work.

- Adult-onset asthma: Some adults, especially women, present with asthma for the first time in their adult life. They tend to be nonallergic and often need higher doses of ICS.

- Asthma with persistent airflow limitation: Some chronic asthma patients develop airflow limitation that is persistent or incompletely reversible.

Demographics

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention data from 2019-2021 has shown the following trends in asthma prevalence with respect to age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.3

- In children younger than 18 years, asthma prevalence increased with age and was more common in males than females.

- In adults older than 18 years, asthma prevalence was higher in females compared to males.

- Asthma prevalence among ethnicities showed the highest prevalence in American Indian/Alaska natives > African Americans > Caucasians > Hispanic Americans > Asians.

- Asthma prevalence increased among impoverished populations as the poverty level increased.

Risk Factors

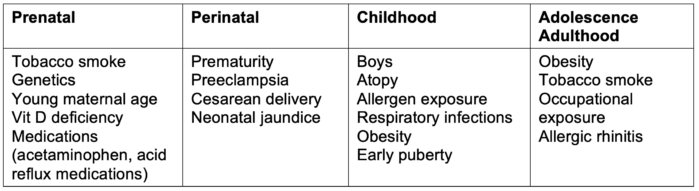

- • Risk factors for developing asthma are listed in Table 1.5

Table 1. Risk factors for developing asthma

Pathophysiology

Allergic Asthma

- Environmental antigens trigger airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness, leading to smooth muscle contraction and narrowing of the bronchial airways, resulting in limited airflow.6,7

- Atopy is the strongest risk factor for developing asthma through IgE antibody-mediated attack on antigens and correlating with total IgE serum levels.6,7

- There are two phases of an asthma exacerbation: early phase and late phase.

- Early phase:

- Environmental triggers initiate the release of sensitized IgE antibodies.

- IgE antibodies bind mast cells and basophils, resulting in cytokine release and mast-cell degranulation.

- This action releases inflammatory products, including histamine, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes.

- The histamine triggers airway hyperresponsiveness and a bronchoconstrictor response along with bronchial secretion and mucosal edema.8

- Mast cells also trigger smooth muscle contraction within the airways, which results in narrowing. Patients present with airflow obstruction and increased work of breathing.

- T-lymphocyte (TH2) cells release interleukin and additional cytokines to keep the inflammatory response underway and facilitate eosinophil and basophil survival.

- Late phase:

- Over time (hours), these inflammatory cells move to the lungs and sites of allergen exposure, maintaining bronchoconstriction and inflammation, worsening lung compliance, and increasing work of breathing.

- Prolonged inflammation within the lungs triggers remodeling, which can lead to complications such as scarring (fibrosis) and irreversible airway obstruction.

- Airway remodeling occurs as a result of sustained inflammation. Fibrosis and hyperplasia may also occur. The epithelial cells lining the airways increase in smooth muscle mass and undergo transition to mesenchymal cells.6 The increased muscular content may facilitate hyperresponsiveness.

- Early treatment to target inflammation and hyperresponsiveness can protect against sustained inflammation and its complications.

Nonallergic Asthma and Others

- While allergic asthma pathophysiology is characterized by IgE-antibody mediated response to allergens, nonallergic asthma does not involve allergen-specific IgE-antibodies. Instead, nonallergic asthma triggers inflammation and bronchoconstriction characterized by oxidative stress, neutrophil activation, increased innate immune activation, etc.9

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of asthma is based on the history of characteristic symptom patterns and evidence of variable expiratory airflow limitation on bronchodilator reversibility testing.1

- Symptoms include wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough. They occur variably over time and vary in intensity. They are often worse at night or upon waking. They can be triggered by exercise, allergens (dust mites, molds, pollen, furry animals), cold air, viral infections, etc.1

- Widespread, high-pitched wheezing is characteristic of asthma; although not specific, it is suggestive of asthma. Physical examination may be normal between exacerbations.

- Lung function is most reliably assessed by spirometry and measurement of forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC). A reduction in the ratio of FEV1 to FVC identifies an obstructive pattern.

- Bronchodilator reversibility testing should document variable expiratory airflow limitation. Responsiveness refers to rapid improvements in FEV1 or peak expiratory flow (PEF) after inhalation of a rapid-acting bronchodilator (for example, 200-400 mcg of Salbutamol) or gradual improvement after initiation of ICS.

- A positive bronchodilator responsiveness on spirometry includes1

- Adults: Increases from baseline FEV1 or FVC ≥ 12% and ≥ 200 mL or increase in PEF ≥20% if spirometry is not available.

- Children: Increase from baseline in FEV1 ≥ 12% predicted (or in PEF of ≥ 15%).

- Other tests that may be useful in diagnosing asthma include1

- Bronchial provocation tests with inhaled methacholine, mannitol, exercise, etc.

- Allergy tests confirming atopy (IgE levels, spin prick tests).

- Fractional concentration of exhaled nitric oxide.

Treatment

Nonpharmacological Treatments1

- Cessation of smoking, environmental tobacco exposure, and vaping.

- Regular physical activity and prevention of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction (warm-up before exercise, SABA or ICS-SABA before exercise)

- Outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programs, breathing exercises.

- Avoidance of exposure to allergens and irritants

- Avoidance of medications that may worsen asthma (aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, beta-blockers) Decision on a case-by-case basis

- A healthy diet and weight reduction in obese patients.

- Strategies for dealing with emotional stress.

- Avoidance of outdoor air pollutants and weather conditions.

Pharmacological Treatment1

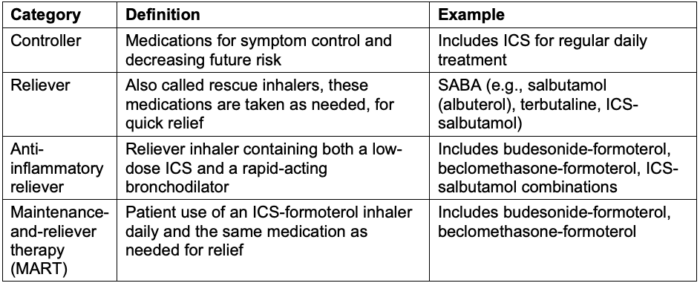

- Pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment for most asthma patients. The categories of asthma medications are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Categories of asthma medications

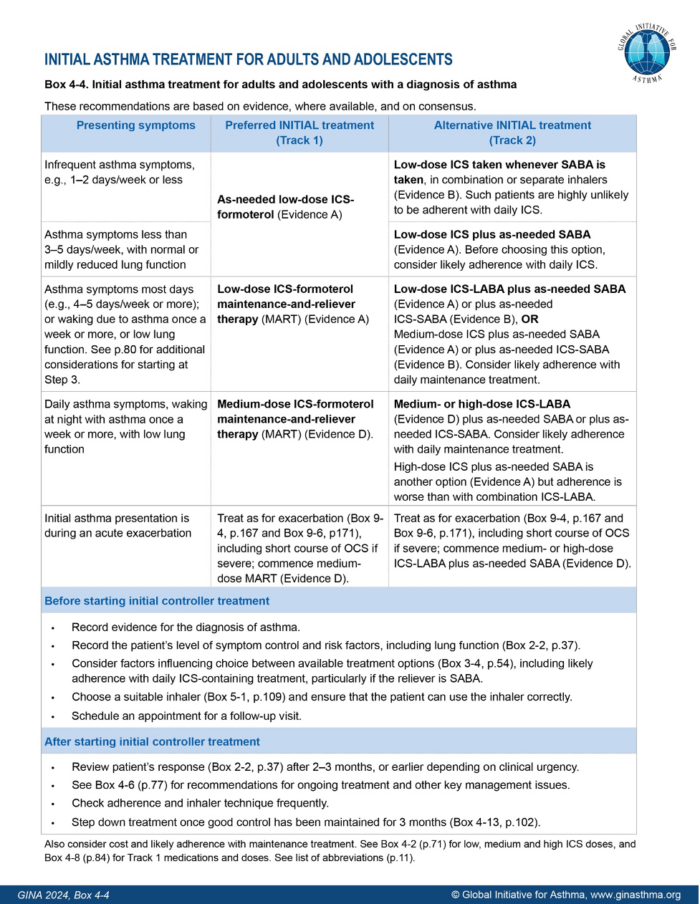

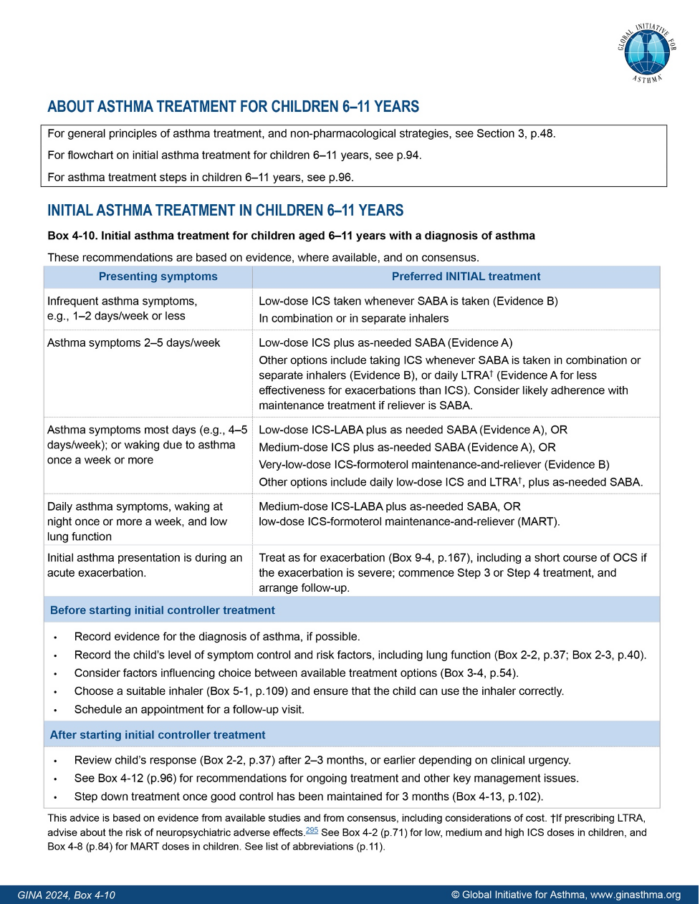

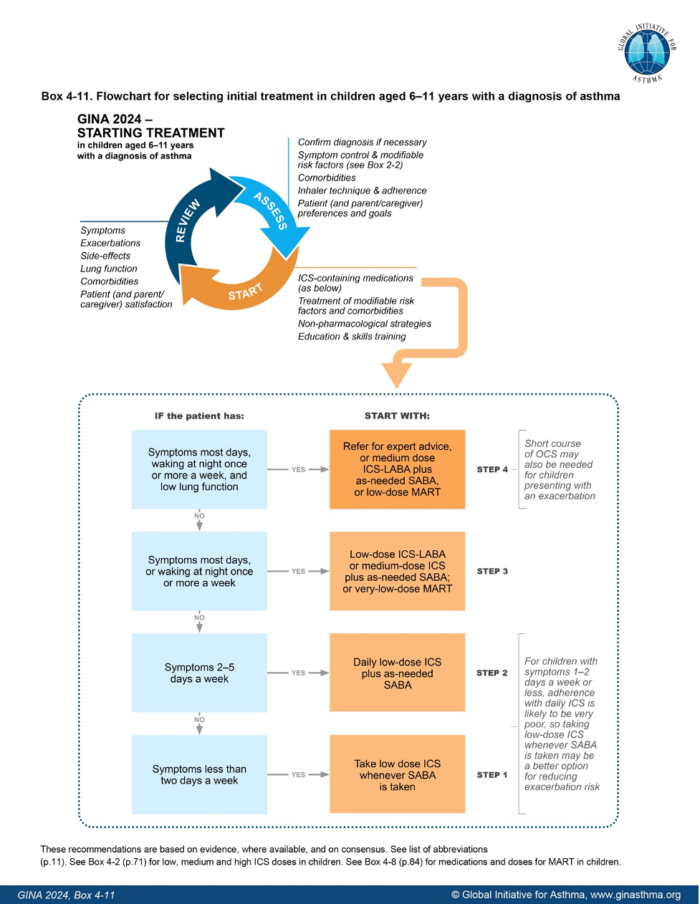

- In 2023, the Global Initiative for Asthma updated recommendations regarding initial therapy. For treatment in adults, adolescents, or children 6-11 years old, a SABA alone is no longer recommended.1 Instead, ICS is recommended to reduce the risk of severe exacerbations and control symptoms.1

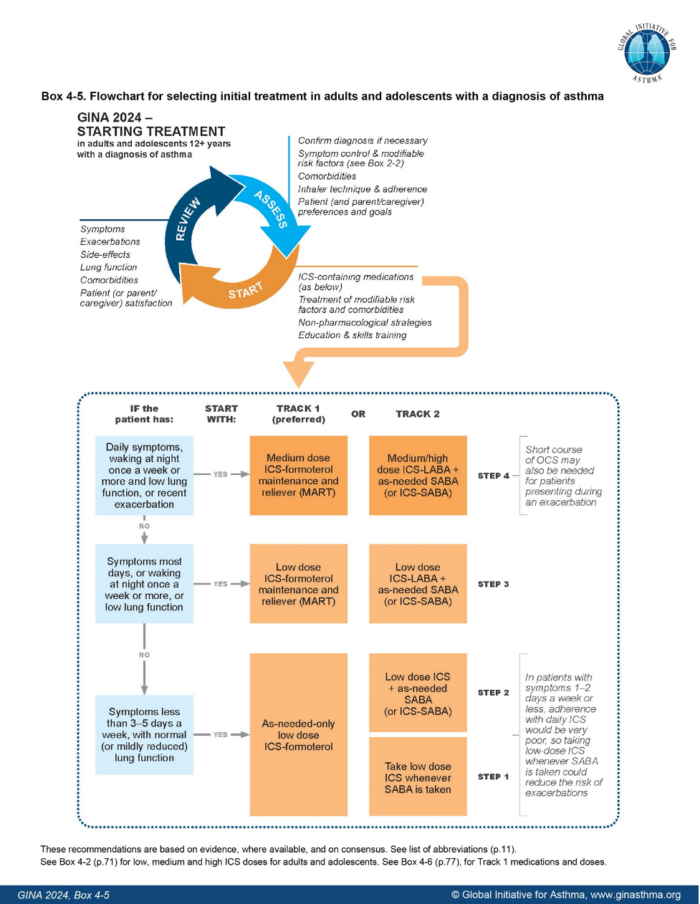

- The following charts specify current GINA treatment recommendations based on severity and control for adults, adolescents, and children ages 6-11 years old, respectively.1 See Boxes 4-4 and 4-5, and Boxes 4-10 and 4-11. Specific medications and dosing information not listed, out of the scope of this review

Figure 1. GINA ©2024 Global Initiative for Asthma, reprinted with permission. Available from www.ginasthma.org

Figure 2. GINA ©2024 Global Initiative for Asthma, reprinted with permission. Available from www.ginasthma.org

Figure 3. GINA ©2024 Global Initiative for Asthma, reprinted with permission. Available from www.ginasthma.org

Figure 4. GINA ©2024 Global Initiative for Asthma, reprinted with permission. Available from www.ginasthma.org

References

- GINA ©2023 Global Initiative for Asthma, reprinted with permission. Accessed July 3, 2024. Link

- Common asthma triggers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published January 22, 2024. Accessed July 3, 2024. Link

- Most recent national asthma data. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed July 3, 2024. Link

- Mallol J, Crane J, von Mutius E, et al. The international study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC) phase three: a global synthesis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2013;41(2):73-85. PubMed

- Litonjua AA, Weiss ST, Risk factors for asthma. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2024. Accessed July 3, 2024. Link

- Sinyor B, Concepcion Perez L. Pathophysiology Of asthma. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan. Link

- Liu M. Pathogenesis of asthma. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2024. Accessed January 4th, 2024. Link

- Yamauchi K, Ogasawara M. The role of histamine in the pathophysiology of asthma and the clinical efficacy of antihistamines in asthma therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20(7):1733. PubMed

- Kuruvilla ME, Lee FE, Lee GB. Understanding asthma phenotypes, endotypes, and mechanisms of Disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56(2):219-233. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.