Copy link

Acute Subdural Hematoma

Last updated: 03/02/2023

Key Points

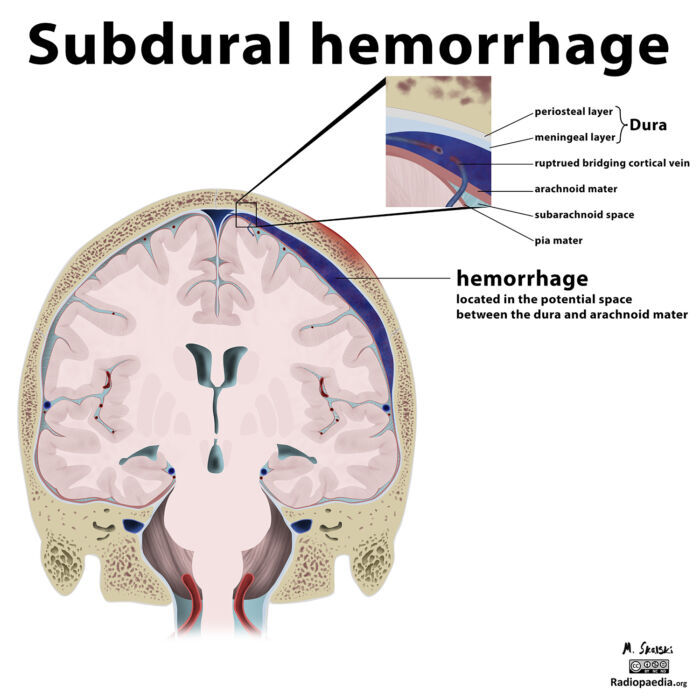

- Subdural hematoma (SDH) is a type of intracranial hemorrhage characterized by bleeding that occurs between the dural and arachnoid membranes surrounding the brain.

- Trauma is the most common cause of SDH.

- Acute SDH commonly results from tearing of bridging veins in the subdural space.

- Acute SDH may be evacuated surgically, resolve spontaneously from resorption, or develop into a chronic SDH.

Introduction

- Subdural hematoma (SDH) is a type of intracranial hemorrhage characterized by bleeding that occurs between the dural and arachnoid membranes surrounding the brain (Figure 1).1,2

- SDHs can be classified into several subtypes based on:2

- Time course: acute, subacute, acute on chronic, and chronic

- Etiology: traumatic, spontaneous, and other pathologies

- Special considerations: anticoagulation-induced, bilateral, recurrent, etc.

Figure 1. A parietal subdural hematoma from a ruptured bridging cortical vein secondary to trauma. Case courtesy of Dr. Matt Skalski, Radiopaedia.org, rID:21542.

Etiology

- Acute SDH results from head trauma about 70% of the time.1

- The acceleration of the brain in the lateral direction can cause injury to the bridging veins.1

- Minor injuries can result in acute SDH in at-risk patients, such as older patients or patients on anticoagulation.

- Nonaccidental trauma is the typical etiology of acute SDH in infants and children. Concern for abuse should remain high.2

- Decreased intracranial pressure (ICP) or intracranial hypotension is another mechanism of acute SDH.1

- Decreased ICP may result from a cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) leak following a lumbar puncture, a ventriculostomy, a shunt placement, excessive drainage from a lumbar drain, or other neurosurgical procedures.1

- The decrease in ICP causes the brain to depress in the skull and puts stress on the bridging vessels.

- Intracranial hypotension can also lead to engorgement of the veins and cause leakage.1

- Any cause of arterial hemorrhage can also lead to SDH, including:

- intracerebral hemorrhage

- ruptured aneurysm

- arteriovenous malformations

- vasculopathy

- SDH can also be the result of an underlying malignancy.

- Acute on chronic subdural hematoma: Chronic subdural hematomas or chronic hygromas have a risk of acute bleeding into the subdural space.

Pathophysiology

- An acute SDH should be suspected in patients with a steadily decreasing level of consciousness and/or unilateral neurological symptoms from compression:

- dilated pupil, focal weakness, hemiparesis, posturing, and/or focal seizure.

- Older patients are at a higher risk for SDH, and mortality increases significantly in patients older than 60 years.2

- Cerebral atrophy results in a larger subdural space, lending more tension on the bridging veins, higher clot burden, and increased midline shift.2

- More comorbid conditions in this population increase the risk of hospital complications.

- Venous SDHs most commonly occur in the frontoparietal region, whereas arterial SDHs are typically found in the temporoparietal region.1

Diagnosis

- A noncontrast head computed tomography (CT) is the first choice imaging study to diagnose SDH. An acute SDH appears as a hyperattenuating mass overlying the cerebral convexity, falx cerebri, or cerebellar tentorium.2 It typically has a crescent-like or half-moon appreance that crosses suture lines (Figure 2). Unilateral SDH may cause a mass effect with midline shift. Chronic SDH appears as isodense to hypodense crescent-shaped lesions that may contain pseudomembranes.

Figure 2. Noncontrast head CT showing large subdural collection along right cerebral hemisphere with blood and fluid densities. It is causing mass effect and midline shift. Case courtesy of Dr. Baqar Hasan. Radiopaedia.org. rID:83781. Link

Treatment Options/Anesthetic Considerations

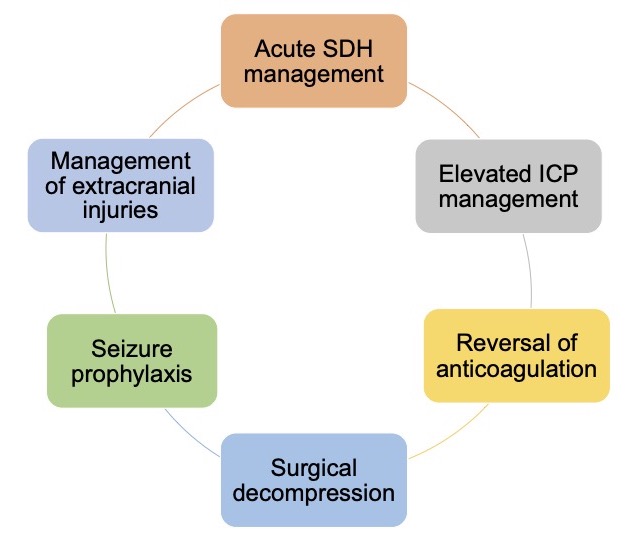

The management of SDH requires a multi-faceted approach (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Multi-faceted approach to acute SDH management. Adapated from Huang KT, et al. The neurocritical and neurosurgical care of subdural hematomas. Neurocrit Care. 2016.2

Acute SDH Management

- Intubation for a Glasgow coma score (GCS) less than 8 or a decline in GCS by 2 or more points should be considered.2

- Adequate oxygenation and ventilation should be ensured.

- Systolic blood pressure should be maintained less than 140-160 mmHg to prevent hematoma expansion.1,2

- Hypotension should be avoided and normotension should be maintained to prevent cerebral hypoperfusion in the setting of elevated ICP.

- Hypercapnia should be avoided, which could trigger an ICP crisis.

- A noncontrast head CT should be repeated to assess for stability at 4 hours if no immediate operative intervention is performed.

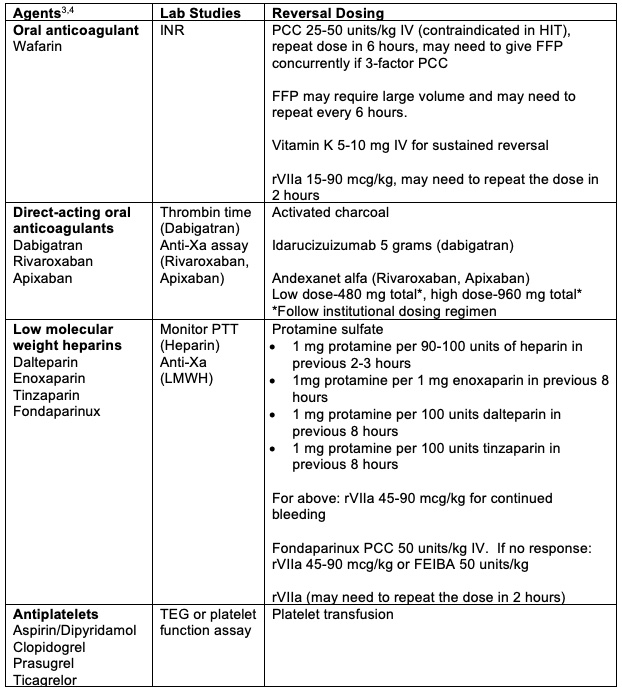

Reverse Any Anticoagulation or Coagulopathy (Table 1).2

Table 1. Reversal of anticoagulation. FEIBA = anti-inhibitor coagulant complex, FFP = fresh frozen plasma, HIT = heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, LMWH = low molecular weight heparin, PCC = prothrombin complex concentrate, rVIIa = recombinant factor VIIa, TEG = thromboelastogram.

Elevated ICP Management2

- Surgical evacuation and decompression are the most effective means of lowering ICP.

- Head of the bed should be elevated.

- Sources of venous obstruction (i.e. improperly placed cervical collar) should be eliminated.

- Hyperventilation is a bridging treatment before surgical evacuation.

- Caution should be taken with the placement of external ventricular drains to remove CSF, as it may worsen the condition by causing further retraction of the injured veins.

- Caution should be taken with osmotic agents, as they may cause further tension on dural vessels exacerbating the hematoma.

Seizure prophylaxis2

- Antiseizure prophylaxis with levetiracetam, lacosamide, or fosphenytoin should be considered.

- Lesions involving the temporal lobe or tentorium can be more epileptogenic.2

- Acute traumatic injuries should include seizure prophylaxis for 7 days.

Operative Intervention2

- Current guidelines recommend open craniotomy for an acute SDH with a maximum thickness greater than 1cm or a midline shift greater than 0.5 cm.

- Smaller lesions may still require surgical intervention if the patient is doing poorly clinically, especially if the GCS decreases by 2 or more points from the time of presentation.

- Traditional ICP management techniques are safer after hematoma evacuation.

- Some institutions will leave subdural and subgaleal drains for a few days after surgery.

References

- McBride W. Subdural hematoma in adults: Etiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. In: September 20th, 2021. UpToDate; 2022. Accessed August 17th, 2022.

- Huang KT, Bi WL, Abd-El-Barr M, et al. The neurocritical and neurosurgical care of subdural hematomas. Neurocrit Care. 2016; 24(2): 294-307. PubMed

- Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood advances. 2018;2(22):3198-225. PubMed

- Freeman WD, Weiz, JI. Reversal of anticoagulation in intracranial hemorrhage. In: June 1st, 2022. UpToDate; 2022. Accessed November 17th, 2022.

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.