Copy link

Acute Ischemic Stroke: Pathophysiology, Cerebrovascular Anatomy, and Stroke Syndromes

Last updated: 04/20/2023

Key Points

- Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) occurs when arterial occlusion leads to lack of brain tissue oxygenation resulting in irreversible neuronal injury and neurological signs and symptoms.

- AIS remains one of the leading causes of death and disability globally.

- Fundamental knowledge of cerebral vasculature anatomy and associated stroke syndromes is essential in the recognition and treatment of AIS.

Introduction

- Stroke is a debilitating disease and represents the second most common cause of death worldwide and the leading cause of serious long-term disability in adults.

- Globally, 60% of all strokes are due to ischemia.1

- In the United States, the etiology of strokes include2

- 87% are due to ischemia;

- 10% are due to intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH); and

- 3% are due to subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

- AIS subtypes according to the mechanism of injury:3

- 30% are due to cerebral small vessel disease;

- 18% are due to large-artery atherosclerosis;

- 20% are due to a cardiac source of emboli;

- 30% are without an identified cause (cryptogenic infarcts); and

- 2% are due to other determined causes, such as arterial dissection or hypercoagulable states.3

- Among the common causes of AIS, large-artery atherosclerosis carries the highest risk of early stroke recurrence, while cardioembolism portrays the highest mortality rate.

- Traditional vascular risk factors associated with common causes of AIS include4

- hypertension

- smoking

- diabetes

- hyperlipidemia

- cardiovascular disease

- obesity

- physical inactivity

- family history of stroke prior to age 65

Pathophysiology

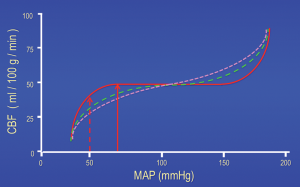

- Cerebral tissue is highly dependent on consistent cerebral blood flow (CBF) for the delivery of oxygen and glucose.

- Acute occlusion of an artery supplying the brain leads to cell injury (ischemia) and death (infarct) when CBF falls below 20mL/100g/minute.

- CBF is directly affected by arterial pCO2 levels. Increases in pCO2 will increase CBF, whereas decreases in pCO2 will decrease CBF.4

- Cerebral vasculature adapts to provide a relatively constant CBF despite changes in systemic mean arterial pressure (MAP), referred to as autoregulation.5 This adaptive mechanism may be overwhelmed when extreme variances in MAPs occur (Figure 1).

- Loss of cerebrovascular autoregulation following ischemic injury further impairs the delivery of oxygen to at-risk tissue, leading to cell death.

Figure 1. CBF autoregulation curves depicting the relationship between MAP and CBF. The solid curve is the classical representation, with a relatively broad plateau phase. The solid vertical arrow indicates an average lower limit of autoregulation for normotensive adult humans of approximately 70mmHg. The 2 dotted line curves represent the variations that occur within a normal population, with some subjects having effectively shorter plateaus and some having very little autoregulatory capacity. Used with permission from Drummond, JC. Blood pressure and the brain: How low can you go? Anesth Analg. 2019;128(4):759-71.5

Cerebrovascular Anatomy

- Focal and abrupt reduction in CBF rapidly leads to cell injury; however, rapid treatment can prevent progression to cell death.

- A fundamental knowledge of cerebral vasculature is essential in the recognition and management of AIS.

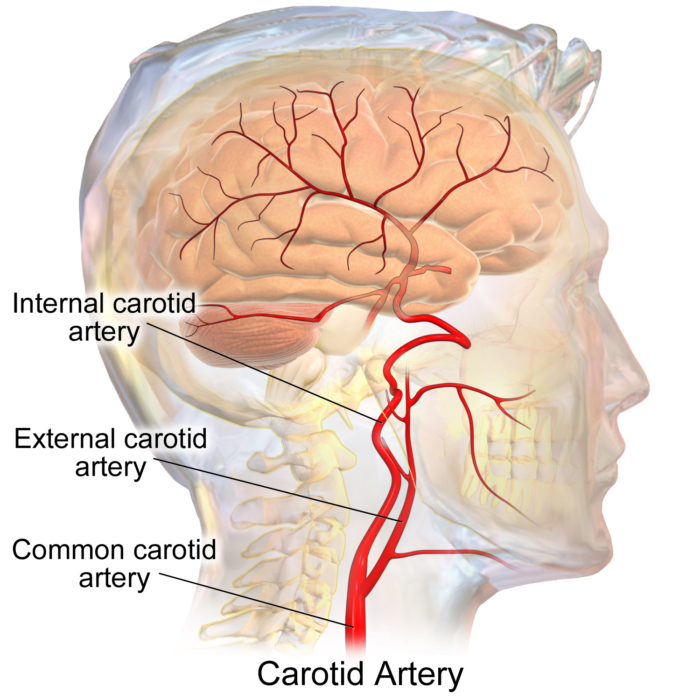

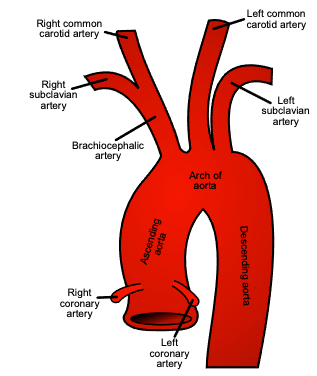

- Cerebrovascular anatomy originates at the aortic arch from which the brachiocephalic, left common carotid and left subclavian artery are derived (Figure 2).

- The brachiocephalic artery forms the right common carotid and subclavian artery shortly after takeoff.

- The vertebral arteries originate from the subclavian arteries.

- The extracranial segments enter the transverse foramen at C6 level and ultimately pierce the dura in the vertebral canal, becoming the intracranial segments.

- Common carotid arteries divide into external and internal carotid arteries at the level of C3-C4 vertebrae (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Branches of the aortic arch. Source: Wkimedia Commons. Henry Vaandyke Carter. Public Domain. Link.

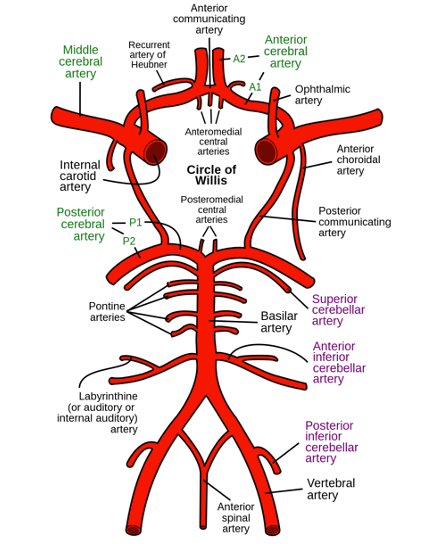

- The circle of Willis connects the anterior (carotid) and posterior (vertebrobasilar) circulation as the major intracranial arterial system (Figure 4).

- The intracranial carotid artery bifurcates into the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and anterior cerebral artery (ACA).

- Prior to bifurcation, the ICA provides smaller branches including the

- ophthalmic artery;

- posterior communicating artery (PCom); and

- anterior choroidal artery.

- Prior to bifurcation, the ICA provides smaller branches including the

- The vertebral arteries form the basilar artery at the pontomedullary junction, which later bifurcates to form the right and left posterior cerebral arteries (PCA).

- The posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) is derived from the vertebral artery prior to the vertebrobasilar junction, while the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) is a branch of the basilar artery.

- The superior cerebellar artery (SCA) originates immediately prior to the termination of the basilar artery.

- The communicating arteries provide anastomosis between arterial branches:

- Anterior communicating artery connects the bilateral ACAs.

- Posterior communicating artery connects each MCA to the respective posterior cerebral artery (PCA).4

- The intracranial carotid artery bifurcates into the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and anterior cerebral artery (ACA).

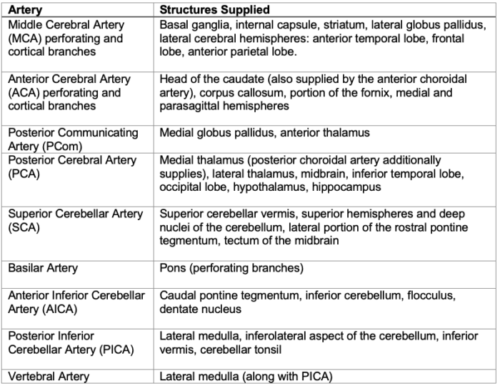

Table 1. Anatomical arterial supply

Stroke Syndromes

- The rapid identification of stroke syndromes can assist in timely treatment and improved outcomes.

- Cortical signs can assist in the identification of large vessel occlusion (LVO):

- aphasia

- gaze preference

- visual field cut

- neglect

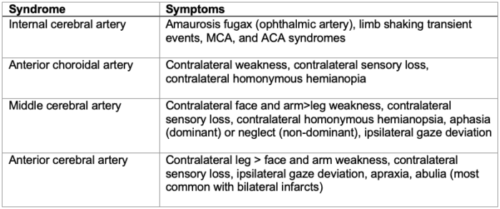

Table 2. Anterior circulation stroke syndromes.6

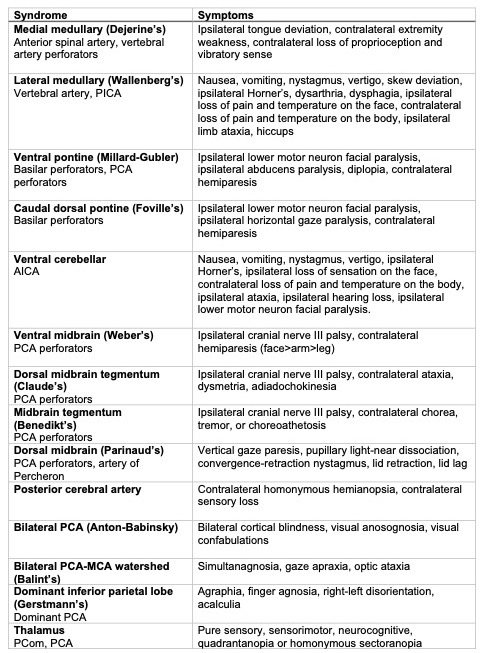

- Posterior circulation stroke syndromes may be overlooked as they frequently present with nonspecific, nonlocalizing signs and symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, and dizziness.

Table 3. Posterior circulation syndromes6

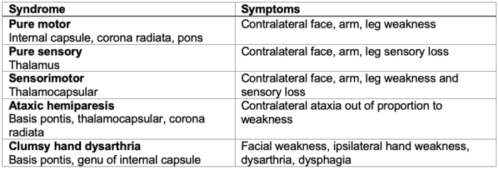

Table 4. Lacunar syndromes6

References

- GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019; a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Neurology. 2021; 20(10):P795-820. PubMed

- Ovbiagele B, Nguyen-Huynh MN. Stroke epidemiology: Advancing our understanding of disease mechanism and therapy. Neurotherapeutics. 2011; 8:319-29. PubMed

- Sacco, RL. Risk factors, outcomes, and stroke subtypes for ischemic stroke. Neurology. 1997, 49 (5 Suppl 4): S39-S44. PubMed

- Grotta, JC., et al. Stroke: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Elsevier Health Sciences. 7th Ed. 2021.

- Drummond, JC. Blood pressure and the brain: How low can you go? Anesth Analg. 2019;128(4):759-71. PubMed

- Brazis PW, Masdeu, JC, Biller, J. Localization in Clinical Neurology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 3rd Edition. 1996.

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.