Copy link

Electroconvulsive Therapy Procedure

Last updated: 01/04/2023

Key Points

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) generally is considered a low-risk procedure, but significant medical comorbidities may complicate anesthetic management.1

- The choice of anesthetic and management of physiologic sequelae of the therapeutic seizure can directly impact both the efficacy and safety of the treatment.2

- Underlying cardiac disease is the most common comorbidity associated with complications during ECT.3

Indications, Contraindications, and Preanesthetic Assessment

- ECT is indicated for the treatment of severe or treatment-resistant depression, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and catatonia.1,3

- Off-label treatment may include movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease or severe autism with self-injurious behavior.1,3

- While there are no absolute contraindications to ECT, there are some medical conditions that require evaluation and optimization:3,4

- Cardiac:

- Unstable coronary artery disease (CAD)

- Decompensated congestive heart failure (CHF)

- Preexisting arrhythmias

- Implantable cardiac devices

- Significant valvular disease

- Pulmonary:

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Neurological:

- Intracranial lesions

- Elevated intracranial pressure

- Known or suspected brain tumor or other pathology

- Cardiac:

- Preanesthetic evaluation can be complicated in the psychotic, uncommunicative, delusional, paranoid, or catatonic patient.4 Psychiatric medications can complicate anesthetic management and may also be unfamiliar to the anesthesiologist (Table 1).

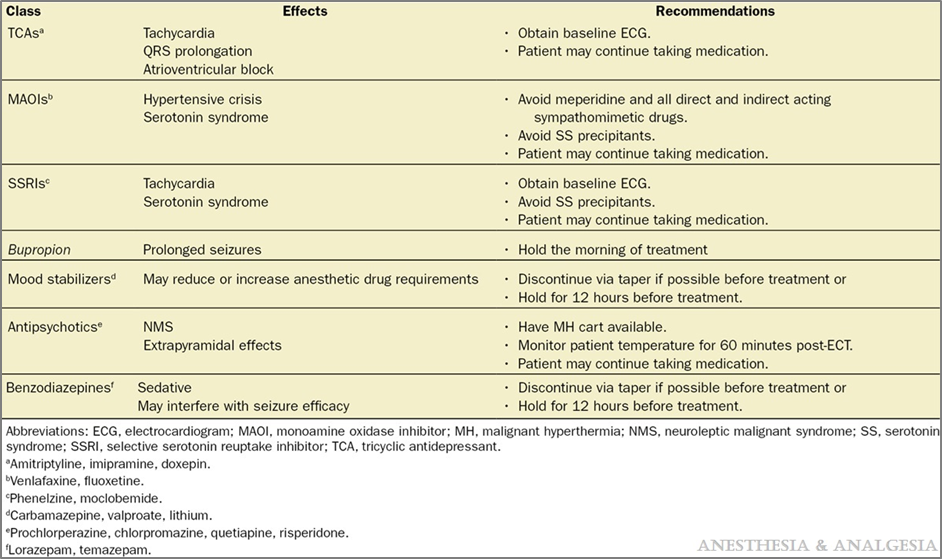

Table 1. Strategy for the management of common psychiatric medication administration during the peri-ECT Period. Reproduced with permission from Bryson EO, et al. Individualized Anesthetic Management for Patients Undergoing Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Review of Current Practice. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(6):1943-56.

Description of ECT

- ECT involves the induction of an electrically generated therapeutic seizure under general anesthesia.

- The procedure is often performed as “non-operating room anesthesia” (NORA) administered in either a dedicated ECT suite, procedure room, or the postanesthesia care unit (PACU).

- Standard American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) monitors including heart rate, blood pressure, ECG, capnography, and temperature are used.

- Intubation for ECT is very rare, but airway equipment should be immediately available, along with a fully stocked code and malignant hyperthermia (MH) cart.

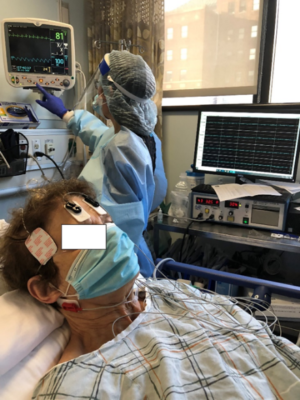

Figure 1. Placement of EEG, EMG, and stimulus pads

Figure 2. Monitoring on neuromuscular blockade in lower extremity

The sequence of events is as follows:

- Preparation involves the placement of an intravenous (IV) line, standard anesthesia monitors, and preoxygenation via nasal cannula or face mask.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG), electromyogram (EMG) and stimulus pads are placed by the treating psychiatrist (Figure 1).

- After the time-out and administration of premedications, general anesthesia is induced via a single bolus dose of medication.

- Once the patient is unresponsive, an assistant inflates a blood pressure cuff around the right ankle above systolic pressure to occlude blood flow and prevent the paralytic from reaching the foot (Figure 2).

- After the cuff is inflated, the patient is paralyzed with succinylcholine or a nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agent.

- Response to the paralytic agent is monitored via peripheral nerve stimulation on the left lower extremity, while the patient is hyperventilated using a bag-valve-mask (BGM) device.

- Once the patient is fully relaxed, an assistant places a bite-block to protect the teeth, and the treating psychiatrist induces the therapeutic seizure.

- Airway support as well as pharmacological management of physiological parameters (if indicated) continues until the paralytic has worn off or has been reversed.

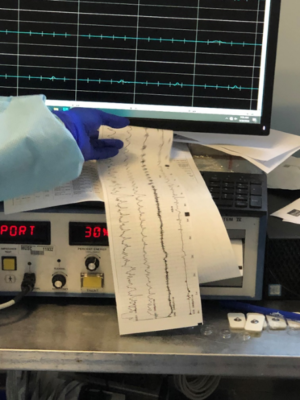

- EEG and EMG are monitored and recorded by the ECT machine (Figure 3).

- If the therapeutic seizure does not spontaneously resolve within 120 seconds, additional anesthesia or a benzodiazepine is administered to break the seizure.

- Once the patient is able to maintain their airway and is hemodynamically stable, care is transferred to the PACU staff.

Figure 3. Monitoring of EMG and EEG by ECT machine

Physiological Response to the Procedure

The expected physiological response to ECT is determined by stimulation of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system:2,4

- During the stimulus, an initial increase in parasympathetic tone results from direct stimulation of the vagus nerve causing bradycardia, a cardiac pause, or asystole.

- Once the therapeutic seizure has begun, an increase in sympathetic tone results in hypertension and tachycardia, which can be significant.

- Hemodynamic changes generally are time-limited and well tolerated in the majority of patients, however:

- persistent poststimulus asystole is rare. A stimulus that doesn’t provoke a seizure may result in prolonged asystole, which may require treatment.

- Patients with demand ischemia or other significant cardiac disease may require treatment during the sympathetic surge.

- Postictal asystole is seen with shorter seizures or in patients with underlying bradycardia and may require treatment.

- The treatment of hypertension related to ECT must be made on a case-by-case basis. Labetalol, esmolol, or nitroglycerin are commonly used for hypertension.

References

- Lisanby SH. Electroconvulsive therapy for depression. N Engl J Med. 2007; 357:1939–45. PubMed

- Kellner CH, Bryson EO. Electroconvulsive therapy anesthesia technique: minimalist versus maximally managed. J ECT. 2013; 29:153–5. PubMed

- Tess AV, Smetana GW. Medical evaluation of patients undergoing electroconvulsive therapy. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360:143. PubMed

- Bryson EO, Aloysi AS, Farber KG, Kellner CH. Individualized Anesthetic Management for Patients Undergoing Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Review of Current Practice. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(6):1943-56. PubMed

Other References

- Byrson EO. Electroconvulsive Therapy Anesthetic Considerations. OpenAnesthesia. Published January 4, 2023. Accessed February 6, 2023. Electroconvulsive Therapy Anesthetic Considerations

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.