Copy link

Carotid Stenosis

Last updated: 01/04/2023

Key Points

- Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and stenting decrease the incidence of cerebrovascular accidents compared with medical management in appropriately selected patients.

- CEA is recommended in moderate and severe symptomatic carotid stenosis when the reduction of stroke risk outweighs the surgical risk.

- CEA is preferred over carotid angioplasty/stenting in low and moderate surgical risk patients.

- Strict hemodynamic control during the intra- and postoperative period is vital to reduce complications such as cerebral hypoperfusion, ischemic stroke, cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome, carotid artery dissection, and neck hematoma.

- Anesthetic management should facilitate electrophysiological monitoring and rapid emergence without significant hemodynamic swings or coughing.

Introduction

- Strokes are the 5th leading cause of death and the leading cause of disability in the US. Patients with carotid stenosis are at an increased risk for strokes.1

- In the 1991 North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET), the two-year stroke endpoint was significantly lower (9% vs. 26%) in patients with high-grade carotid stenosis, who underwent CEA when compared with medical management.2

Surgical Options and Patient Selection

- Surgical options include:

- CEA;

- endovascular (stenting);

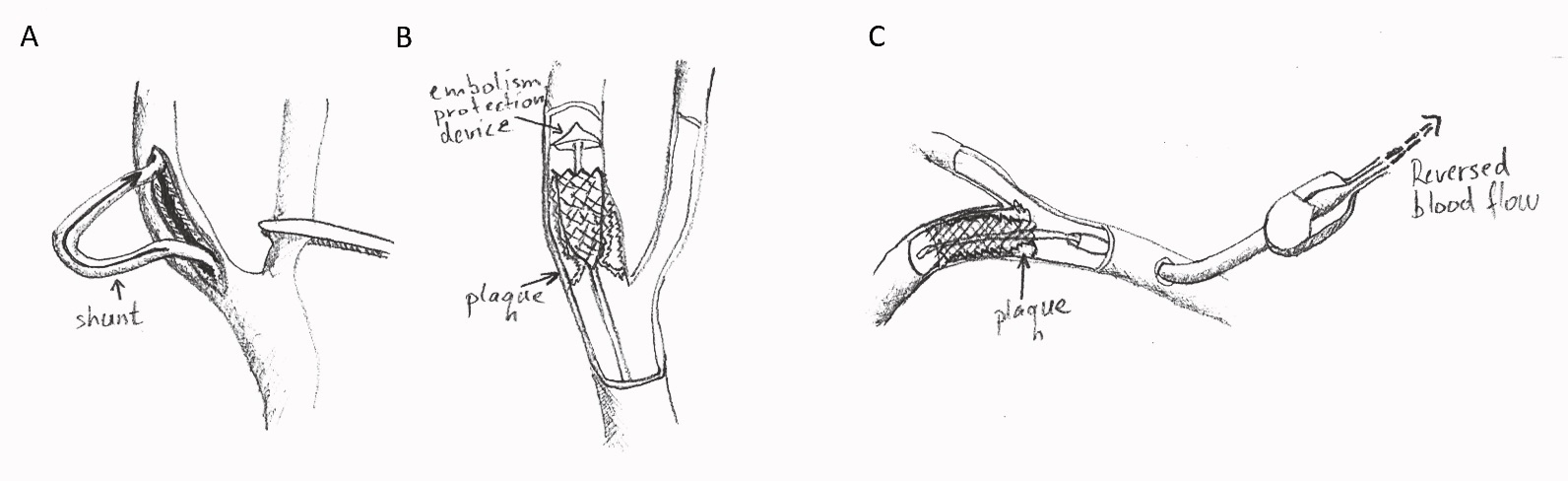

- transcarotid artery revascularization (TCAR) involves deploying a stent through direct surgical cutdown over the carotid artery (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Surgical options in carotid stenosis. A: Carotid endarterectomy involves the removal of the plaque through an open surgical incision. A shunt may be placed to provide continuous blood flow to the brain during surgical manipulation. B: Endovascular stenting. An endovascular stent is advanced to the stenosis over a catheter equipped with an embolism protection device. C: Transcarotid artery revascularization. A stent over a catheter is advanced into the lumen of the internal carotid artery via direct surgical cutdown over the common carotid artery. The blood flow in the carotid artery is reversed during stent deployment to reduce the risk of embolism. The advantage of TCAR is a reduced risk of embolism.

- CEA is recommended as the first-line treatment for symptomatic low-risk surgical patients with a stenosis of 50% to 99% if the perioperative risk of stroke or mortality is <6%.3,4 The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one stroke over two years is 9 for men and 36 for women.

- CEA is recommended for asymptomatic patients with stenosis of 70% to 99% if the perioperative risk of stroke and death is <3%.4

- In patients with a recent nondisabling stable stroke, carotid revascularization should be performed after 48 hours but within 14 days of stroke to achieve the greatest risk reduction for perioperative stroke or death.3,4 (NNT=5)

- Carotid stenting over CEA may be beneficial for high surgical risk patients or for patients with unfavorable neck anatomy.3,4

- Guidelines recommend against revascularization in patients who have experienced disabling strokes or have altered consciousness. Revascularization can be considered after neurological recovery.4

Anesthetic Considerations

- Surgical manipulation of the carotid sinus during CEA or stenting can cause abrupt activation of the baroreceptors leading to bradycardia and hypotension mediated through the baroreceptor reflex arc (Figure 2).1

Figure 2. Baroreceptor reflex. Stretch receptors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch activate in the setting of hypertension and deactivate in the setting of hypotension. Activation of receptors sends signals to the nucleus solitarius in the medulla through the Hering and vagus nerves. This results in the activation of parasympathetic nervous system and deactivation of sympathetic nervous system, resulting in decreased heart rate and decreased total peripheral resistance/blood pressure. This can result in myocardial ischemia in patients at risk for cardiovascular events.

- Cessation of manipulation resolves hemodynamic compromise, and lidocaine infiltration can prevent episodes intraoperatively.1 Furthermore, denervation of carotid sinus baroreceptor during surgery can contribute to hypertension postoperatively.1

- Both regional anesthesia (RA) and general anesthesia (GA) can be used for CEA. The GALA trial, a multicenter randomized control trial in 95 centers in 24 countries, compared regional and general anesthesia for CEA and showed no difference in outcomes (perioperative death, myocardial infarction, stroke, etc.).5

- RA typically involves superficial cervical plexus block and local anesthetic infiltration. Deep cervical plexus is not routinely performed secondary to the risk of subarachnoid injection causing high spinal, and unwanted block of the phrenic, recurrent laryngeal, and vagus nerves as well as the paraspinal sympathetic chain causing Horner’s syndrome.1

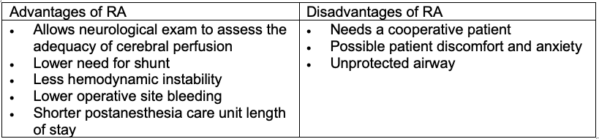

Table 1

- General anesthesia typically includes standard ASA monitors, preinduction arterial line, using small incremental doses of an induction agent, neuromuscular blockade, endotracheal intubation, and maintenance of GA with a volatile agent and short-acting opioids.

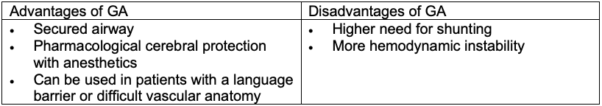

Table 2

- Intraoperative hemodynamic goals include:

- maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP) close to baseline;

- increase MAP during cross-clamp placement to promote contralateral cerebral blood flow through the circle of Willis;

- decrease MAP prior to cross-clamp release to avoid hyperperfusion and intimal tear;

- maintain MAP at baseline when the shunt is in place to maintain adequate perfusion.

- Avoid coughing on emergence to reduce the risk of hematoma.

- Control blood pressure on emergence to avoid hyperperfusion. Have vasoactive drugs ready to either raise (e.g., phenylephrine, ephedrine) or reduce blood pressure (e.g., calcium channel blockers (clevidipine or nicardipine), or short-acting beta-blockers (esmolol).

- Aim for rapid emergence for neurological exam and consider ICU care postoperatively for frequent neurological checks.

Monitoring and Shunting

Intraoperative monitoring of hypoperfusion and ischemia are commonly used. The clinical utility is to identify patients who may benefit from shunting during the period of carotid clamping, blood pressure augmentation during surgery, or change in surgical technique.1 However, there is limited data that cerebral ischemia monitoring improves patient outcomes.

- The gold standard for monitoring is the awake patient under cervical plexus block and local anesthesia. Use is a function of the surgeon’s experience. It requires a cooperative patient and is no longer commonly used.

- Electroencephalography (EEG): Both EEG and processed EEG have been used. Raw EEG, especially using higher number of channels (e.g., 16 channels) is more sensitive than processed EEG. However, EEG changes are not specific for ischemia and are more useful to detect global cerebral hypoperfusion.1 EEG also does not detect small cortical or sub-cortical strokes.

- Evoked potentials (EP) (somatosensory and motor-evoked potentials) can help detect hemispheric ischemia causing compromise of the motor and sensory pathways, which are at risk of ischemia during CEA. The validity of EP monitoring for CEA has not been established.1

- Transcranial doppler (TCD) provides continuous measurement of blood flow during clamping (e.g., hypoperfusion) and after cross-clamp release (e.g., hyperperfusion) and also allows detection of microembolic events in the middle cerebral artery.1 While TCD monitoring holds promise, conclusive benefits have not been reported.

- Carotid artery stump pressure measures retrograde pressure resulting from collateral flow via the circle of Willis.1 Though this technique is inexpensive, easy to obtain, and continuously available, there is limited evidence for improved outcomes and few centers use it.

- Carotid artery shunting: The value of shunting lies in uninterrupted cerebral perfusion and unrushed surgery. Despite the theoretical benefit, there is insufficient evidence to support selective shunting in response to changes in neuromonitoring signals or routine shunting vs. no shunting during carotid endarterectomy.6

Postoperative Considerations

- Postoperative neurological complications following CEA are usually related to surgical technique. Thromboembolic factors (embolization or thrombosis at site) are more likely to be the cause than hemodynamic factors (hypoperfusion).1

- Hypertension is common in the postoperative period. Surgical denervation of the carotid sinus baroreceptors is the most likely cause. Pain, full bladder, hypoxia, hypercarbia, etc. must be excluded and the blood pressure should be aggressively controlled.

- Cerebral hyperperfusion syndrome from altered cerebral autoregulation can cause an abrupt increase in cerebral blood flow and manifest as cerebral edema, hemorrhage, petechiae, and seizures. This complication usually manifests several days after a CEA.

- Postoperative hypotension may also occur from carotid sinus baroreceptor hypersensitivity or reactivation.

- Wound hematomas are not uncommon. In the NASCET trial, 5.5% of patients developed wound hematomas. Most cases are from venous oozing and require no more than external compression for 5-10 minutes. Rapidly expanding hematomas require prompt attention and surgical drainage.

References

- Shalabi, A and Chang, J. Anesthesia for Vascular Surgery. In: Gropper, M; et al. Miller’s Anesthesia, Ninth edition. Philadelphia; Elsevier; 2020: 1855-65.

- Barnett HJM, Taylor DW, Haynes RB, et al. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325(7): 445-53. PubMed

- Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al. 2011 ASA/ ACCF/ AHA/ AANN/ AANS/ ACR/ ASNR/ CNS/ SAIP/ SCAI/ SIR/ SNIS/ SVM/ SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease: executive summary. Circulation. 2011;124(4):489-532. PubMed

- AbuRahma AF, Avgerinos ED, Chang RW, et al. Society for Vascular Surgery clinical practice guidelines for management of extracranial cerebrovascular disease. J Vasc Surg. 2022;75(1S):4S-22S. PubMed

- Lewis SC, Warlow CP, Bodenham AR, et al. General anaesthesia versus local anaesthesia for carotid surgery (GALA): a multicentre, randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2008; 372(9656): 2132-42. PubMed

- Chongruksut W, Vaniyapong T, Rerkasem K. Routine or selective carotid artery shunting for carotid endarterectomy (and different methods of monitoring in selective shunting). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Jun 23;2014(6):CD000190. PubMed

- Chongruksut W, Vaniyapong T, Rerkasem K. Routine or selective carotid artery shunting for carotid endarterectomy (and different methods of monitoring in selective shunting). PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.